Religious and Sufi Music of Afghanistan: Structures, Functions, and Cultural Contexts

An overview of the structures, performance practices, and cultural roles of religious and Sufi music in Afghan society.

Religious and Sufi Music of Afghanistan: Structures, Functions, and Cultural Contexts

Author: Islamuddin Feroz, Former Professor, Department of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University

Abstract

Religious and Sufi music in Afghanistan constitutes an important part of the country’s cultural and artistic heritage. Various forms, such as Naʽat recitation, Madah, Qawwali, Maqam, and Dhikr, are performed across different regions of Afghanistan, reflecting local and cultural variations. In addition to their artistic value, these musical forms play a significant role in religious education, the transmission of moral concepts, and the reinforcement of social bonds within Afghan Muslim communities. Some forms are accompanied by traditional instruments such as the rabab, daf, and dayereh, while others are performed without any musical instruments. Performances often involve improvisation, vocal repetition, and specific rhythmic patterns, creating a distinctive mystical and spiritual atmosphere. This study, drawing on historical sources, musical texts, and field observations, analyzes the structure, functions, and applications of these musical forms, demonstrating that religious music in Afghanistan continues to be preserved as a living component of the country’s cultural, ethnic, and religious identity.

Keywords: Afghanistan, religious music, Sufi music, na‘t, maddahi, qawwali, maqam, dhikr.

Introduction

Religious and Sufi music in Afghanistan is an inseparable part of the country’s culture and identity and plays an important role in religious ceremonies, mystical rituals, and social life. Since ancient times, religious chants and hymns have served not only as a means of praising God and the prophets, but also as tools for conveying moral values and religious teachings to society. Genres such as na‘t-khwani, maddahi, qawwali, maqam, and dhikr are performed in various regions of Afghanistan with distinct local and cultural characteristics, each contributing uniquely to the strengthening of religious and social bonds.

Na‘t-khani and maddahi are primarily devoted to praising Almighty God and then the Prophet of Islam and other religious figures, and they are usually performed either extemporaneously or based on specific vocal structures. In contrast, qawwali, especially in khanqahs and shrines, is a collective and mystical form that combines improvised vocals, specific rhythms, and vocal coordination among participants. In addition, qasida, maqam, and dhikr are examples of religious music that, besides their artistic value, also hold ritual and religious functions. The performance of these forms of religious music is often accompanied by traditional instruments such as the rubab, daf, and dayereh, although some forms, like dhikr, are performed without instruments. These features demonstrate the flexibility and diversity of religious music in Afghanistan and its role in ritual and social contexts.

This study, through an analysis of historical texts, field observations, and available sources, examines the structure, application, and function of these musical genres in Afghanistan. The aim of this research is to identify the place of religious and Sufi music as a living and dynamic part of Afghan culture and to explore its role in transmitting religious and social concepts to society.

Ritual Music in Pre-Islamic Afghanistan

Historical studies and evidence indicate that religious and Sufi music in Afghanistan has its roots in the ancient traditions and pre-Islamic rituals of this land. Among the most prominent examples of this heritage are the Vedic hymns—chants that not only served ritualistic and religious functions, but also reflected some of the earliest patterns of melody and musical composition (Michael, 2023, p.14). The reciters of these hymns, known as Rishis, were simultaneously spiritual leaders, poets, and musicians who, through melodic performance of prayers and hymns, created an atmosphere of spiritual grandeur in devotional ceremonies (Kohzad, 1946, p.49).

Other examples of this historical continuity can be found in the Pishdadian and Kushan periods. During these eras, music played a central role in transmitting culture, narrating myths, and relating religious stories; hymns and melodies held a special place in festivals, worship rituals, celebrations, and mourning ceremonies (Nusservanji Dhalla, 1922, p.11). Furthermore, the oldest part of the Avesta—the Gathas, attributed to Zoroaster—were sung in praise of Ahura Mazda, and are recognized as the earliest documented heritage of poetry and music in the region (Mirza, 2004, pp.21–23). Beyond their ritual value, these chants also played an influential role in teaching religious principles and strengthening cultural cohesion within communities.

With the advent of Islam, earlier intellectual and musical traditions did not disappear; rather, a process of integration and transmission emerged among Buddhist, Zoroastrian, and Islamic teachings, and Sufism along with Islamic philosophical thought continued along the trajectory of those ancient traditions. Thus, many earlier intellectual elements were preserved in a renewed form within the Islamic tradition, and the Sufi musical heritage not only survived but was re-created in new genres such as dhikr, sama‘, na‘t-khwani, qawwali, and qasida-khwani.

Many of the vocal structures, chanting techniques, collective rhythms, and circle-based rituals in Sufi music can be seen as Islamized forms of Vedic-Avestan traditions. Moreover, the presence of words and concepts such as sama‘, but, sanam, shaman, sorud, gāt/gāthā, jashn/yesht, along with a range of music-related rituals in the Sufi traditions of Khorasan, shows that Afghanistan’s religious music is a fusion of pre-Islamic Aryan-Vedic heritage and Islamic-Sufi interpretation. Therefore, Afghanistan’s religious music is not a disconnected tradition, but a continuous and dynamic chain of ritual experiences that has persisted from antiquity to the present day (Nile, 2016, p.5).

Overall, Sufi and mystical music grew significantly after the spread of Islam throughout the cultural realm of Khorasan, and—shaped by religious and social transformations—became one of the essential components of spiritual experience among Muslims. In Afghanistan, this musical tradition gained a firm place especially in khanqahs, zawiyas, and gatherings of dhikr and sama‘, and was gradually systematized by various Sufi orders and spiritual lineages. The continuity of this tradition within society enabled Sufi music to acquire not only a spiritual and devotional function but also become an integral part of the cultural heritage and ritual identity of this land.

In what follows, the most important types of Sufi and religious music used in Afghanistan are introduced—genres that each possess their own vocal structure, performance style, and ritual function, and have played a significant role in shaping and sustaining the spiritual culture of the society.

Na‘t

In the past, na‘t reciters were among the most important narrators and performers of religious stories during evening gatherings, festivals, and religious ceremonies. They typically recited and narrated classical texts such as Saadi’s Gulistan and Bustan, Rumi’s Mathnawi, and other literary and mystical works for the audience, thereby playing a significant role in transmitting cultural and religious heritage. This group of religious performers sought, through a specific form of devotional singing, to make the atmosphere of the gathering more impactful and appealing to the listeners. In addition, they transmitted their skills and knowledge related to vocal performance to those interested in this tradition. Na‘t-khwani is most often performed as free, non-metric singing, in which verses may at times be extended, shortened, or placed in varying meters. In some cases, na‘t recitation is also accompanied by musical instruments.

One of the greatest na‘t reciters of Afghanistan was Mir Fakhruddin, who expressed his devotion to the family of the Prophet (PBUH) through composing and performing devotional poetry and songs, and who trained many students in this field. Mir Fakhruddin, the son of Mir Abdullah (1322–1385 AH), began performing na‘t in 1338 SH, joined the circle of na‘t reciters in Kabul, and performed in khanqahs, gatherings, ceremonies, and on Radio Television Afghanistan. He had memorized numerous hymns, supplications, and na‘ts by various poets and performed them in his own distinct style and pleasant vocal tone. The themes and content of na‘t recitation revolve around the lives of prophets and religious figures and describe their spiritual status; these are composed and performed on religious occasions such as Ashura, Mawlid al-Nabi, and sometimes during funeral ceremonies (Madadi, 2011, pp. 74–199).

Maddahi

Maddahi is one of the branches of religious music in the Islamic world that differs significantly from other musical genres in terms of performance structure, mode of expression, and cultural functions. The content of maddahi is generally based on religious principles and includes praise of God, eulogies of the prophets, religious narratives, and concepts related to the world, the hereafter, and mysticism. In Afghanistan, maddahs (religious eulogists) are generally divided into three distinct groups:

1. Itinerant maddahs who perform without instrumental accompaniment;

2. Ritual maddahs who perform only on religious occasions;

3. Ceremonial maddahs who are not itinerant but perform with instruments during religious–mystical events.

1. Itinerant Maddahs

In the past, itinerant maddahs played an important role in promoting devotional texts. They typically performed in marketplaces and villages and received money or food in return for their performances. Their singing was often free, improvisational, non-metric, and performed in flexible poetic meters. Over time, the presence of itinerant maddahs has declined, and this form of performance has diminished.

2. Ritual Maddahs

Ritual maddahs are those whose activities are closely tied to the liturgical calendar and religious events. They usually appear during the months of Muharram and Safar, on Ashura, in the month of Ramadan, Mawlid al-Nabi, and other religious occasions, performing elegies or devotional chants. Their main characteristic is the dependence of their artistic and religious activity on specific times of the year, with performances typically held in mosques, takiyakhanehs, hosayniyahs, or private gatherings. Ceremonial maddahs, in addition to their artistic role, contribute significantly to conveying historical–religious concepts, strengthening religious emotions, and fostering social cohesion among participants.

3. Maddahi with Instrumental Accompaniment

In the Pamir regions, instrumental maddahi holds a special place and is performed during mourning ceremonies, religious rituals, and mystical gatherings. The people of Badakhshan regard this music as part of their spiritual and cultural identity and treat it with deep reverence. Maddahi performances are usually based on hymns of praise, na‘t, and mystical poetry, and are carried out as solo or group singing. The maddahs, who have inherited this knowledge and skill from their ancestors, are the sole practitioners of this musical form; other musicians are not permitted to perform this sacred music. The religious music of Badakhshan, in terms of structure, style, and performance content, bears no resemblance to other Pamiri musical traditions. Maddahs of this region typically perform their pieces using poetry from Rumi’s Diwan-e Shams, the works of Jalaluddin Balkhi, Nasir Khusraw Qubadiani, Khanjari, and other poets and mystics. The main instruments used in this musical tradition are the Pamiri rubab, daf, and zirbaghali (Adeli Hosseini, 2025).

Dhikr

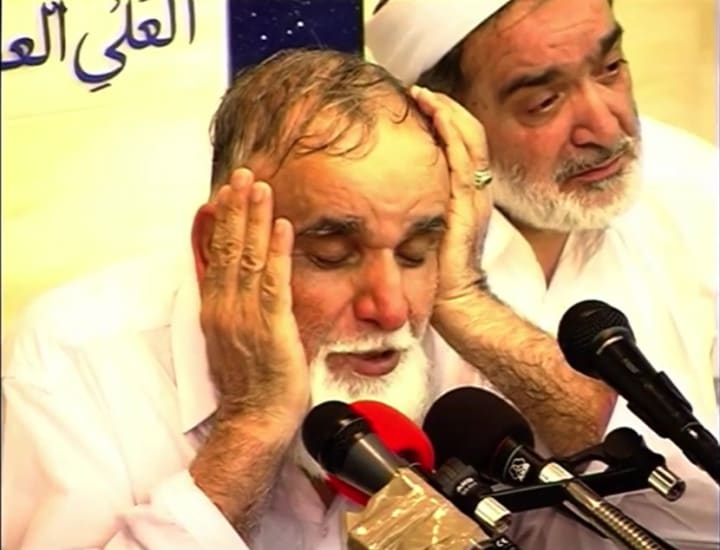

Dhikr is one of the most important forms of Sufi music in Afghanistan and is widespread across most regions of the country. This ritual is typically performed without musical instruments, with the focus on the repetition of sacred words and devotional murmurs. In this form of religious singing, the dhakkars (participants) repeat phrases such as “La ilaha illallah,” “Allah,” and “Huwa,” accompanying the lead singer while performing dhikr in a regular rhythm and within a structured circular formation. This method is commonly referred to as Dhikr Jali and is conducted collectively in khanqahs on designated days. During the ceremony, the sheikh sits in the Mahal-e-Tawhid, the central place of dhikr within the khanqah, and disciples form a circle on his right and left according to the order of their initiation into the Sufi path. In Afghanistan, dhikr is performed both in a standing and seated posture; for example, in the khanqahs of Kabul it is usually performed seated, whereas in the khanqahs of Herat it is performed standing. Dhikr in Afghanistan is not only a collective act of worship but also an opportunity to strengthen social cohesion and spiritual bonds among disciples. Beyond its religious dimension, it carries significant cultural and artistic value. Some dhikr gatherings also provide newcomers to the Sufi order the opportunity to become acquainted with Sufi etiquette and teachings, fostering a deeper understanding of the spiritual path of the order (Noor Ahmad, 2021).

Qasida-Khwani

Qasida-khwani is an important part of devotional music in Badakhshan province and other northern provinces of Afghanistan, typically performed during religious ceremonies and mourning rituals with instruments such as the daf and rubab. Singing a Qasideh is called a "Qasideh" for this reason: it follows the structure, meter, and rhyme of the Qasideh poem, and the music helps convey the meaning of the poem. Structurally, a qasida is usually lengthy and composed of multiple verses with uniform meter and rhyme. The rhyme begins in the first couplet and is maintained throughout the poem. Qasidas are generally used to express themes such as praise and eulogy, description, supplication, wisdom, mysticism, and occasionally satire or lamentation. Therefore, any poem that is composed in a long, coherent form with a consistent rhyme and meter and addresses these themes falls within the qasida category.

The musical structure of a qasida generally includes three sections:

1. Tarchini: The opening section, performed with an emphasis on the lower tonal registers.

2. Rab-Pai (Two-Beat): A smoother and simpler section in which the coordination between instrument and voice becomes more prominent.

3. Owj Maqam: The final section, serving as the climax of the qasida performance.

During qasida-khwani ceremonies, maintaining the sanctity of the gathering is obligatory. Participants are not permitted to engage in conversation, disruptive behavior, or neglect the proceedings. If such behavior occurs, the Mir Majlis (master of ceremonies) reprimands the disruptive individual and, in some cases, may expel them from the assembly of elders (Qasemi, 2011, p.9).

Qawwali

The most important form of religious music in Afghanistan is qawwali, which is primarily performed in khanqahs or during certain religious occasions, especially in the holy month of Ramadan and Mawlid. It is performed by a group of six to ten individuals, accompanied by the tabla or dohol and a harmonium. This form consists of astayi (opening section), entre, and sometimes improvisation. The vocal sections are initially sung by the lead singer and then repeated by the chorus. The vocal range of qawwali songs is generally wide, and the lyrics focus on the praise of God (SWT) and the description of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The rhythm is often in 7/8, 6/8, or 2/4, accompanied by prominent clapping. This form is popular not only in Afghanistan but also in India and Pakistan.

Qawwali is a branch of mystical music that dates back six centuries. Sufis who performed collective songs of their masters’ poetry during mystical ceremonies came to be known as qawwals. During performances, qawwals sit in a specific arrangement in two, three, or sometimes four rows. The use of dohol and a specific type of harmonium is essential. The vocal performance of qawwali is often accompanied by movements of the head, hands, and body. These gatherings typically begin after the evening (Isha) prayer and may continue until dawn. Qawwali is most often performed in khanqahs and shrines.

The term qawwali derives from the Arabic word qawl, meaning the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). A qawwal is one who repeatedly recites these sayings, and qawwali refers to what the qawwal recites. Some historians trace the emergence and establishment of this style to the 8th century AH in the Khorasan region. Qawwali is a branch of mystical and traditional music. One of the foremost figures in the development and popularization of this form was Amir Khusro Dehlavi, a 7th-century AH poet and musician of Khorasani origin. As a master of Indian and Khorasani music, he reached the court of the Sultan of Delhi and introduced Khorasani and Arabic instruments, familiarizing the court with the concepts of tarana and qawl. Qawwali songs are usually performed in Persian, Punjabi, and Urdu. Regional variations are evident in the vocal style and pronunciation. Although some verses of qawwali may seem worldly on the surface, they are in fact deeply mystical and spiritual. The main themes of qawwali lyrics are love, devotion, and longing for God, the Prophet (PBUH), and the saints (Awliya).

Sections of Qawwali:

1. Hamd: Beginning with praise of the Creator

2. Na‘t: Praise and description of the Prophet (PBUH)

3. Maqamat/Munqabat: Eulogizing the virtues of Amir al-Mu’minin Ali (AS) and Sufi masters

4. Marsiya: Mourning for Imam Hasan and Imam Husayn (AS) and the events of Karbala

(Kamali, Ghafoori, Qorbani, 2015, p.37)

Qawwali Poem:

I know not what abode it was, the night where I was,

Everywhere, a dance of veils, the night where I was.

A fairy-shaped beauty, tall as cypress, tulip-faced,

She was all the heart’s fire, the night where I was.

Rivals pricked their ears at her voice, she in grace, I in fear,

How hard it was to speak a word, the night where I was.

God Himself was the lord of the gathering, in a realm beyond all place,

Muhammad (peace be upon him) the candle of the assembly, the night where I was.

Among Islamic orders, only followers of the Chishti order perform qawwali with musical instruments. In other orders, playing instruments is not permitted. In the Chishti order, qawwali is performed with instruments such as the rubab, harmonium, tabla, and dohol (Mouns, 2011, p.66).

Maqam

The concept of “Maqam” in Afghan music became widespread after the advent of Islam and during the period when this region was known as “Khorasan,” gaining particularly broader usage after the Timurid era in Herat. Scholars attribute the beginning of the term’s use to the 7th century AH; for instance, Qutb al-Din Shirazi mentioned it in his treatise Durrat al-Taj li-Ghurrat al-Dibaj. However, another group attributes its earliest usage to Abd al-Qadir Maraghi, a prominent 9th-century AH musician (Ederer, 2011, p. 26).

Nevertheless, this concept has survived in Afghan music to the present day in various forms and continues to be performed as a type of Islamic or religious music. The religious form of this genre is commonly observed in the musical cultures of the Pashtun and Tajik communities of Afghanistan. It appears that the use of this term for such religious songs is related to the spiritual and moral aspects of their lyrics; in many cases, the beginning of any gathering or performance starts with the name of God and the expression of ethical themes, which likely explains why these forms came to be called “Maqam.”

In Pashto music, a Maqam usually consists of more than ten to twelve couplets and literally refers to a “place” or “rank.” This form is particularly prevalent in the music of Nangarhar and Kandahar, where every musical gathering begins with a Maqam before performing Chahar Baiti, Badal, Baghti, or other forms. Maqams are typically performed with a slow, prolonged rhythm and accompanied by moral themes. During the performance, the atmosphere of the gathering is calm and focused, and listeners pay attention with respect. After the Maqam concludes, the singer moves on to more lively forms such as Loba, Chahar Baiti, Baghti, or Ghazal, transforming the mood of the gathering from somber or contemplative to joyful and energetic.

Maqam Poem

Do not extend your hand in friendship to someone of low origin.

Do not be fooled by their empty or flashy clothing.

Friendship with the low-born is like buying a red donkey.

Ultimately, they will bring you to ruin.

Do some kindness with those of noble origin.

Goodness and prosperity will return to you in life.

From the low-born, you will never find loyalty.

This proverb is common everywhere, among both commoners and nobles.

When you see them from afar, they flee from you.

O Golestan, do not treat them with goodwill.

Similarly, in the music of the Tajik communities of Afghanistan, particularly in the music of the Panjshir region, the maqam is performed before the beginning of the qarsak. The performance of the maqam begins with praise and glorification of God. During the performance, and at the end of each poetic rhyme, two individuals spontaneously accompany the main singer. After this, the qarsak is accompanied by the daf or dayereh, as well as by the clapping of people gathered around the singer. Throughout the performance of the maqam and at the end of each rhyme, two singers accompany the main vocalist with a trembling type of voice; these singers are called qashq-goy. During the recitation of the maqam, immediately after the praise and glorification of God, a poem in the form of a riddle is presented to the singer as a challenge; for example:

I offer praise to the Lord

I speak from a restless heart

I recite the eulogy of the leader of all beings

I speak it countless times, day and night

After a “sohbat” (a part of the vocal performance) in the qarsak section, during which the singing is accompanied by the rhythm of the daf and clapping, it is the turn of the opposing performer. He then begins to recite the maqam, and at the end of the maqam, having answered his opponent’s question in this manner, he proceeds to perform the qarsak:

Listen to a tale that took place in the spring,

There, Khalil was amidst the sparks of fiery waves.

Gabriel then brought two drops of water,

And the water came by the command of the Lord.

In this way, the “maqam” section comes to an end, and the audience requests the singer to perform a sangardi piece—a composition whose content is sometimes epic and sometimes descriptive. Sangardi pieces function like a mirror, reflecting the realities of social life, particularly the ways of living and the culture of the indigenous people of Panjshir. Through the study and analysis of these oral songs, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of the society and people of this region of Afghanistan from a cultural and literary perspective (Ahadi, 2011, p. 26).

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that religious and Sufi music in Afghanistan, beyond being merely an artistic phenomenon, constitutes a fundamental component of the society’s cultural and ritual system, playing a significant role in reinforcing and reproducing religious, social, and ethnic identities. Various forms of this music, including na‘at recitation, maddāḥī, qawwali, qasīda, maqām, and dhikr, each serve as distinct vocal and ritual frameworks, performing specific functions in religious occasions and Sufi gatherings. Analysis of these forms reveals that maqām, qasīda, and maddāḥī, with their emphasis on the praise of the Prophet Muhammad and religious figures, convey ethical and instructive messages, whereas qawwali, as a collective and mystical form, reflects the deep connection between music, spiritual experience, and the emotional alignment of participants. Na‘at recitation and dhikr, beyond their aesthetic dimensions, serve ritualistic and educational purposes, playing a prominent role in khānqāh sessions and Sufi assemblies. Examination of performance practices shows that improvisation, repetitive rhythms, and the formation of dhikr circles are crucial in generating spiritual states and strengthening communal bonds. The use of traditional instruments, such as the rabab, daf, and dayereh, in certain forms of religious music further demonstrates the adaptability of religious rituals to incorporate local elements, reflecting cultural flexibility. Overall, the results of this research suggest that religious and Sufi music in Afghanistan not only conveys religious, ethical, and social messages but also functions as part of the society’s cultural memory, playing a sustained and impactful role in preserving the religious and mystical identity of the people. The continuity of these traditions amid social and political transformations underscores their vitality and resilience, highlighting their potential for further scholarly inquiry in ethnomusicology, anthropology, and cultural studies. Moreover, this music can act as a bridge between generations and diverse communities within Afghanistan, providing a profound insight into the country’s ritual culture.

References

Adeli Hosseini, Seyed Jafar. (2025). Customs and Rituals of Mourning on the Martyrdom Anniversary of Imam Husayn (A) and His Companions in Afghanistan. Retrieved from https://www.ocj-af.com

Ahadi, Fazl-Aḥad. (2011). Panjshir Folk Culture. Kabul: Khayyam Publications.

Ederer, Eric Bernard (2011). The Theory and Praxis of Makam in Classical Turkish Music 1910-2010. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California, Santa Barbara.

Kameli, Heda, & Ghafouri, Atieh. (2015). Ritual Ceremonies and Their Discourse with Urban Space in India. Art and Civilization of the East Quarterly. pp 3–44.

Khozad, A. A. (1946). History of Afghanistan (Vols. 1–2). Kabul: Government Printing Press.

Madadi, Abdol-Wahhab. (2011). The History of Contemporary Music of Afghanistan. Tehran: Hozeh-ye Honari Publications.

Michael Witzel (2023). The Realm of the Kuru Origins and Development of the First State in India. Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies.

Mirza, Raiomond. (2004). The House Of Song Musical Structures In Zoroastrian Prayer Performance. London: Published by ProQuest LLC(2017).

Moones, Mohammad Mateen. (2011). Sufism and Mysticism in the Poems of Contemporary Mystics. Kabul: Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan.

Nile, Green. (2016). Afghanistan’s Islam A History and its Scholarship. California: University of California Press. Project MUSE. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/book.63381.

Noor Ahmad, & Khalifa Sahib. (2021). Halaqah Dhikr [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=plU-ZvfooTA

Nusservanji Dhalla, Maneckji. (2007). Zoroastrian civilization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Qasemi, Wahid. (2011). The Nuances of Music: Traditional Music of Badakhshan, Herat, and Badghis. Kabul: Armanshahr Foundation Publishing.

Zhwak, Mohammad Din. (1991). Afghan Music. Kabul: Ariana Printing Press.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.