Percussion and Wind Instruments in Afghan Music: A Historical and Cultural Study

This study explores the historical and cultural significance of percussion and wind instruments in Afghanistan, highlighting their roles in military, ceremonial, and social contexts.

Percussion and Wind Instruments in Afghan Music: A Historical and Cultural Study

Author: Islamuddin Feroz, Former Professor, Department of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University

Abstract

Throughout history, Afghan music has reflected the cultural identity, social transformations, and ritual traditions of the people of this land. Among its instruments, percussion instruments such as drums and wind instruments such as the trumpet (shofar) and karnā have held a fundamental place in the structure of martial and ceremonial music. An examination of these instruments from the Vedic and Zoroastrian periods to the Median, Kushan, Pre-Islamic, Sassanid eras, and subsequent Islamic periods shows that their function extended beyond artistic expression: in battlefields, they served as a means to issue military commands, maintain coordination, motivate troops, and demonstrate political power. This study, relying on historical evidence, archaeological data, and literary sources—particularly Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh—explores the continuity and evolution of drums and trumpets within the historical context of Afghanistan. The findings indicate that these instruments transitioned from purely martial roles to ceremonial, ritualistic functions and symbols of political authority, becoming an integral part of Afghanistan’s musical heritage and cultural identity.

Keywords: Afghanistan, Military Music, Drum, Trumpet, Karnā, Dohol, Sorna, Shahnameh

Introduction

Music in the culture and history of Afghanistan occupies a deeply rooted and multilayered position, one that is not only linked to aesthetic and artistic dimensions but also intertwined with social, military, ritual, and political structures. From ancient times to the Islamic periods, music has consistently been a key tool for expressing collective emotions, establishing communication, and transmitting messages during both peace and war. In this context, percussion and wind instruments—especially drums, trumpets, and karnās—have played a prominent and distinct role. Unlike many melodic instruments, their function was not limited to producing music; they also served as tools for military command, coordination among combatants, and the announcement of rituals and formal ceremonies.

The sound of the drum on the battlefield symbolized order and coordination, while the trumpet’s call signaled attack, retreat, or alarm. These instruments, particularly during ancient periods—from the Vedic and Zoroastrian eras to the Median, Achaemenid, Kushan, and Pre-Islamic kingdoms—were extensively employed, and historical records and ancient texts clearly emphasize their presence in ceremonies, wars, and religious rituals. In Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the sounds of kettledrums, karnās, trumpets, and tabors are repeatedly mentioned in the context of battles and royal ceremonies, demonstrating the key role of these instruments in the martial and ceremonial systems of the people of this land.

With the advent of the Islamic period, although social and political structures transformed, the presence of military music and percussion and wind instruments persisted. During the Ghuri, Timurid, Safavid, Durrani, and even modern periods, naqqāra-khānas (drum towers) and military music ensembles were integral to state ceremonies and army organization. This study, employing a historical and analytical approach, examines the evolution, military function, and cultural significance of drums and trumpets in Afghan music, highlighting their importance in maintaining martial traditions and the cultural identity of the region.

Historical Use of Drums and Trumpets in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is a country with a long and ancient history, whose rich musical heritage carries national values such as freedom, patriotism, solidarity, peace, brotherhood, and dignity, passed down through generations. Examining the role of music in the history and culture of this land reveals that music has influenced nearly every aspect of Afghan life and has consistently played a vital and functional role. Music addressed both the social and psychological needs of people during war and peace: in war, to strengthen morale and resistance, and in times of peace, to foster coexistence, acceptance, and collective celebrations.

Contemporary historians and researchers in Afghanistan, including Azizuddin Wakili Fufalzai, Abdul Rahman Khan, Faiz Muhammad Katib Hazara, Mir Ghulam Muhammad Ghubar, Ali Ahmad Khazad, and Habibullah Habib, as well as some international scholars, have noted the presence of music in ceremonies and wars both before and after Islam. These studies show that music, beyond entertainment, has been an inseparable part of the cultural and social history of the region.

One of the most important components of Afghan music is wind and percussion instruments, which have played a key role in national ceremonies, public festivals, and even battlefields. Historical evidence indicates that during the Vedic period, Aryan tribes employed a wide array of musical instruments. Contemporary researcher Dhanalakshmi mentions the four primary instruments of that era and notes that various drums, such as dandubi and adambara, wooden flutes, cymbals, and string instruments like the vina, along with Sama chants, were used in yajna (sacrificial) ceremonies (Dhanalakshmi, 2021, p.72). The dandubi drums, for example, were a type of clay drum made by hollowing the ground and covering it with skin, initially used to signal danger or warn of enemy attacks. Over time and in later centuries, these instruments also served as stimulants for armies on the battlefield. Additionally, wooden drums and cymbals were primarily used to accompany dance and social ceremonies.

Wind instruments also played an important role in Vedic ritual music, especially wooden flutes, which were considered among the main musical tools of that era. During festivals and celebrations, music and dance functioned as central instruments of collective enjoyment and were often performed outdoors in the presence of men and women. Chants and melodies, accompanied by rhythm and instruments, constituted an essential part of religious and ritual ceremonies, adding beauty and grandeur to ceremonial festivities (Swami, 1973, pp.38).

Evidence found in Zoroastrian texts, particularly the Vendidad, indicates that the use of the trumpet dates back to the era of Jamshid, the first king of the Aryan peoples, and that this instrument played a prominent role in the rituals and ceremonies of ancient times. These texts narrate that Jamshid ruled during a golden age, a period of moderate climate with no disease or death. When a harsh winter began, Ahura Mazda, Jamshid’s deity, tasked him with transferring plants, animals, and humans to an underground refuge, providing him with two tools to accomplish this mission: a golden Sufra and a gilded Ashtra. While some commentators have interpreted these terms as “shield” and “whip,” J. Duchesne-Guillemin clarifies that the Sufra was actually a trumpet used to summon animals, a power also attributed to Exus trumpets. Furthermore, some of these trumpets were made of gold, symbolically linking them to Jamshid (Lawergren, 2003a, p. 94). Gold, due to its brilliance and value, has been recognized across many cultures as a symbol of immortality, power, and wealth. In Jamshid’s story, this metal is associated with divine kingship, connection to the higher realm, and symbolizes the splendor, authority, and the golden era of his rule.

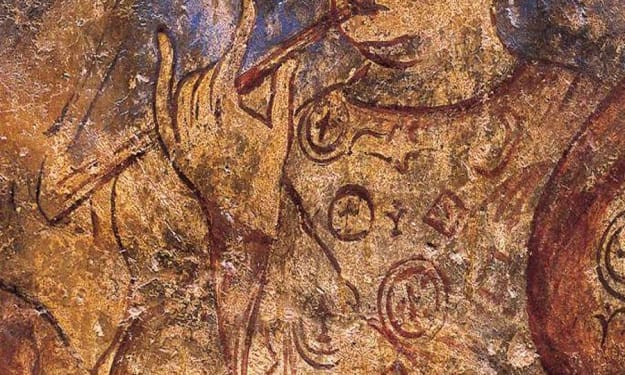

Modern archaeological findings also corroborate these narratives. In recent years, approximately forty small trumpets have been discovered in the oases of Bactria and Margiana, in northern Afghanistan and southern Uzbekistan. Although similar to contemporary instruments, these trumpets are shorter and consist of a narrow pipe connected to a flared bell at the end. Most were made of silver, while some were made of gold and copper (Lawergren, 2003, pp. 66–95). Based on this evidence, it can be concluded that during the Pre-Islamic (Pishdadian) period, loud instruments such as drums and trumpets played a central role in both social and military life, and their presence in battlefields, celebrations, feasts, mourning rituals, and festivals was highly prominent.

In the military domain, when an army prepared for battle, the king would issue a signal, and drums mounted on elephants were sounded to establish order and coordination in the ranks. Simultaneously, karnās, trumpets, and dohols would announce the commencement of battle to all forces, boosting the morale and fighting spirit of the soldiers (Nusservanji Dhalla, 2007, p.11). Ferdowsi, in the Shahnameh, recounts scenes in which loud instruments played roles both in martial arenas and in the festive rituals of the Pishdadian era. He shows that celebrations were generally accompanied by the sounds of karnās, war drums (kos), and trumpets, while soldiers, together with war elephants and musicians, enhanced the grandeur of these ceremonies. Cities, from Zabul (Sistan, Afghanistan) to Kabul, were adorned with colorful banners, and the sounds of flutes, harps, trumpets, and bells filled the air, creating a stunning, vibrant, and music-rich atmosphere (Ferdowsi, 2002, pp. 105–148). Ferdowsi describes Kabul as a beautiful city with joyful people and storytellers, emphasizing that music not only brought delight and joy but, in harmony with nature, imparted a poetic and spiritual dimension to life.

However, the function of music in the Pishdadian era was not limited to celebration. The beats of the kos and the calls of the karnā played a vital role on battlefields, inciting soldiers and stirring their enthusiasm and combat fervor. The formidable sound of these instruments during combat resonated like thunder, shaking the earth and sky, while soldiers, responding to the resonant calls and shouting, marched proudly and resolutely toward battle (Ferdowsi, 2002, pp. 84–100, 144). These instruments, in addition to generating excitement and morale, created strict order within the ranks, ensuring coordination during battle—an essential factor for victory. Nusservanji writes:

"When war with the enemy was announced, the people were informed by the sound of brass trumpets. Watchmen relayed the news to warriors and commanders outside the capital, and soon soldiers from nearby and distant regions arrived in the royal courtyard, accompanied by the loud sounds of trumpets, flutes, and drums. The troops were then organized according to wartime requirements, with drums and dohols mounted on elephants. After completing military preparations, the king inspected the army. As the troops paraded before the king, they left the city amidst the sounds of trumpets, drums, Indian bells, horns, kos, flutes, neylabak, and cymbals. The army marched toward the battlefield to camp there. Upon sighting the enemy, neylabaks and trumpets sounded, gongs and bells rang, and cymbals, drums, and tabira were struck to signal the attack. News of the fall of an enemy hero in single combat or the total defeat of the enemy, quickly spread among the troops, was celebrated with the thunderous shouts and excitement of warriors, accompanied immediately by the sounds of drums, trumpets, dohols, tabira, gongs, and bells" (Nusservanji, 1922, p. 135).

Historical evidence indicates that the use of wind and percussion instruments in the musical culture of the Aryan peoples was not confined to a specific period but continued clearly from the Kayanian era through subsequent periods. In the epic and historical writings of these times, including Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the role of these instruments is explicitly highlighted. Ferdowsi, in his account of the grand reception of Siyâvash by Kay Kāvus, the Kayanian king of Balkh, provides a prominent example of the presence of martial and ceremonial instruments. He reports that upon receiving news of Siyâvash’s arrival, Kay Kāvus ordered that renowned heroes such as Giv and Tous, at the head of a decorated army, proceed to greet him accompanied by nay-e royin (metal trumpet) and kos (war drum) (Ferdowsi, 2002, p. 319).

The use of these instruments was not purely musical; the nay-e royin and kos served as symbols of power, grandeur, and military order in the ceremony. Their formidable sound not only announced the arrival of a prominent figure like Siyâvash but also enhanced the ceremonial splendor of the event. Following the performance of these instruments, dignitaries bearing gold and jewels came to welcome Siyâvash and praised him, demonstrating the connection of music with rituals of reception, social honor, and courtly celebrations. Furthermore, it is recorded that the performers continued the festivities for a week with joyful songs and melodies, reflecting the role of musicians in creating ritual and ceremonial atmospheres during the Kayanian era.

All this evidence confirms that martial wind and percussion instruments played a decisive role in formal and military ceremonies and that music was an important tool for displaying the power, unity, and divine glory (farr-e izadi) of rulers. This musical tradition continued in periods following the Kayanians. For instance, during the reign of the Aspa kings, the sound of horns accompanied by the kos, Hindidari, trumpets, and karnā held a prominent place in military ceremonies. These instruments, in addition to signaling troop movements or the arrival of warriors on the battlefield, had tactical functions, such as instilling fear in the enemy or signaling the defeat of a faction and permitting troops to retreat (Ferdowsi, pp. 913–917, 945). Such applications demonstrate that military music was an inseparable part of troop organization, the transmission of immediate messages, and the creation of coordination on the battlefield.

The same pattern is observed during the Median period. Historical sources report that when Deioces, the first king of Media, ascended the throne, the sounds of kos and trumpet horns echoed from all directions, illustrating the connection of music with coronation rituals, political ceremonies, and public celebrations (Asari, 2002, p. 144). Moreover, Alonzo explicitly notes that the Medes used drums and trumpets during battle to boost soldiers’ morale, maintain order, and guide them, as these instruments could transmit military messages over long distances while simultaneously enhancing collective coordination (Alonzo, 1898, p. 38).

This tradition continued into the Achaemenid period, especially under Cyrus the Great, becoming not only persistent but more organized. Xenophon reports that in Cyrus’ army, martial songs were often performed with simple yet effective rhythms, accompanied by drums and trumpets. These musical performances played a fundamental role in establishing marching rhythm, increasing military coordination, boosting soldiers’ morale, and fostering a sense of unity and collective strength (Xenophon, 2011, p. 141). Such descriptions indicate that music, particularly wind and percussion instruments, was a part of the psychological and military strategy of rulers, playing a vital role in preparing soldiers mentally for battle and executing future tasks.

Historical sources also document the use of percussion and wind instruments in battles, celebrations, and Greek rituals. For instance, Khazad reports that Alexander the Great, during his campaigns in Ariana (present-day Afghanistan and its surroundings), deliberately used drums to manage the battlefield and maintain coordination among his forces. The war drum, or dohol, played a key role in establishing order, transmitting commands, and inducing rapid action in military engagements. According to his account, Alexander, aided by the distinctive sound of the drum, would signal the start of an attack or the time to retreat, and soldiers promptly executed the orders upon hearing these sounds (Khazad, 2010, p. 418).

Plutarch’s accounts also confirm the communicative role of wind instruments. He notes that during Alexander’s time, the sounding of trumpets signaled an immediate attack, prompting the troops to rush toward the enemy without delay (Plutarch, 2008, p. 15). Similarly, Karydaki, in his report of one of Alexander’s battles in India, states: “When Avisiaries, the ruler of Kashmir, rebelled, Alexander, seeking to act quickly, ordered that trumpets be sounded throughout the camp at midnight; then, the cavalry advanced to various points along the shore, ready to cross at the signal of the trumpets” (Karydaki, 1932, p. 83).

These pieces of evidence indicate that the trumpet, like the drum, functioned as a strategic tool for rapid message transmission in situations where verbal commands could not be delivered. Consequently, loud instruments such as drums and trumpets played a fundamental role throughout ancient Afghan history, both on the battlefield and in social ceremonies and celebrations.

This extensive use is also evident during the Parthian (Arsacid) period. Herodian reports that in Parthian rituals, the combination of flute melodies with the pounding rhythm of drums formed a crucial component of religious ceremonies and festivities. This musical coordination not only had an artistic function but was also applied in martial exercises, ritual dances, and preparations for war. According to him, dancing to the rhythm of drums could have significant psychological effects, boosting morale, motivation, and collective cohesion. These traditions, rooted in Aryan culture, were transmitted over centuries to Central Asia and present-day Afghanistan, profoundly influencing the development of ritual dances and music in these regions (Herodian, 1961, p. 1126).

Plutarch also reports that the Parthians, in their wars against the Romans, used large kettle-like drums that caused confusion and anxiety among Roman soldiers, producing a significant psychological impact. These drums, similar to Indian drums, were likely made of clay, covered with a tightly stretched animal hide, and secured with cross straps. Additionally, small bronze bells or rattles were suspended inside. When struck, they produced a deep, terrifying roar, resembling a combination of animal howls and thunder. These heavy, large drums were probably transported by camels trained to tolerate their noise, and it is believed that specialized soldiers were trained to play them (Uwe, 2021, p. 189).

Valuable evidence regarding percussion instruments also survives from the Kushan period. Historical and archaeological sources from this era frequently mention “hourglass-shaped drums,” so-called because of their distinctive form—narrow in the middle and wide at both ends. These drums were membranophones, typically played by hand. Evidence suggests that such instruments were common in India at least one or two centuries before the Common Era and entered Afghanistan through India during the Kushan period (first centuries CE), later spreading throughout Central Asia. In addition to written sources, artistic depictions of these drums have been identified at sites such as Tila-Tepe in Bactria (Afghanistan), Darah-yi Hisar in Tajikistan, Topraq-Qal’eh in Khwarezm (Uzbekistan), and even in the Khotan oasis of Chinese Turkestan, indicating the cultural and artistic reach of these instruments during the Kushan era (Nikonorov, 2000, p. 76).

Entering the Sassanian period, the role of music and martial and ceremonial instruments not only persisted but became more organized and structured. According to the writings of Herodotus and Xenophon, later confirmed by contemporary researchers, the Sassanian court maintained large musical ensembles operating in three primary domains: court music, military music, and folk music. In Sassanian military music, large drums, karnās, trumpets, and naqqāras played a vital role in signaling troop movements, issuing warnings, establishing order, and boosting soldiers’ morale. These instruments could be heard over great distances and thus represented one of the most effective means of communication in warfare (Sheedfar, Asadi Farsani & Arjomand, 2014, p. 1648). Ferdowsi also clearly references the use of loud martial instruments during the Sassanian period, highlighting their importance in military traditions. In describing Kay Khosrow’s battle with Afrasiyab, he shows that instruments such as chakāv, tabira (large war drums), and trumpets and karnās (symbols of trumpets and karnās) were used to announce the start of battle, coordinate the army, and inspire awe and combat fervor (Ferdowsi, 1994, p. 216).

After the advent of Islam, the use of these instruments continued to hold importance both on battlefields and in festive and celebratory rituals, attracting attention during the reigns of various rulers in Khorasan (modern Afghanistan). Habibi (1988, p. 584) writes about drumming in Khorasan: “The drum and kos were used to inform troops and convey commanders’ orders; for example, in the battle between the allied forces of the Khagan, the ruler of Sogd, the Sahib of Shash, Khotan, Chighuya Tukharistan, and the Turks with the Muslims in Jowzjan in 119 AH (737 CE), the Khagan ordered the kos to signal the troops to withdraw. However, his forces were engaged in battle and could not return. The withdrawal was signaled three times with drumbeats, but ultimately they were defeated, and the Muslims seized all their possessions. Afterwards, the Khagan restored the drums and kos in Upper Tukharistan, and this tradition of using drums in battle has continued among Afghan tribes from ancient times to the present”.

During the Tahirid period, military rulers used instruments such as karnās, drums, and war trumpets to create excitement and coordination within the army (Akbari, 2012, pp. 282–321). Similarly, historical sources indicate that the Saffarids employed trumpets and drums in warfare, reflecting a kind of martial ritual prevalent in that era (Bahar, 2002, pp. 279, 288, 298). It is reported that ‘Umar ibn Layth al-Saffar, a ruler of this dynasty, had a special practice in his court: at the end of each year, he would order two special drums, named Mubarak and Maimun, to be played so that all soldiers and courtiers would be aware of the day of gifts and rewards, demonstrating the ruler’s justice and generosity (Gardizi, 1984, p. 314).

Moreover, in the military music of this period, the use of loud and large instruments was common; their primary purpose was to instill fear and awe in enemy forces. Historical records show that in the Samanid era, musical instruments fulfilled diverse roles, with war instruments producing loud and sharp sounds (Abdumutalibovich, 2022, pp. 528–533). For example, Gardizi (1984, p. 371), in describing the battle between Abu ‘Ali Simjur and Sabuktigin in 384 AH, notes that the sounds of drums, trumpets, dohols, gavdam, cymbals, karnās, warriors’ cries, and horses’ neighs filled the battlefield and spread fear among enemy troops. The dohol not only served as a tool for communication and signaling the presence of soldiers on the battlefield but was also used in national and public celebrations. For instance, when the royal procession moved, whether heralds announced news of the king to the people or warriors returned victorious from battle, the dohol, along with other instruments and songs, was played—a tradition that has persisted among Afghan tribes to the present day (ibid, 1984, p. 620).

Jalali also notes that during the Ghaznavid period, their army possessed various symbols, including flags, spears, umbrellas, kos, drums, trumpets, and karnās, all of which represented the unity and spiritual value of the military. The kos, drum, and trumpet, during movement and on the battlefield, demonstrated the army’s grandeur and encouraged combat, constituting a form of military music in the Ghaznavid era. By the order of the Ghaznavid sultans, generals were required to bring a number of musicians, and numerous musical groups were present on the battlefield (Jalali, 2009, p. 110).

Bihqi also mentions the presence of musicians during the Ghaznavid period, writing that a Hindu named Tilak, who was initially a translator and interpreter and later became a military commander, had his own musicians, and in his residence, following Indian aristocratic custom, daf and drums were played (Kadirov, 2000, p. 613). He further notes that upon the army’s return, drummers and trumpeters, along with entertainers, would go out to welcome them (Bihqi, 1994, p. 46). Ghobar adds that musicians in the Ghaznavid court were an integral part of the royal household, and receptions of foreign ambassadors were conducted in the most magnificent manner, accompanied by the sound of karnās and kos (Ghobar, 1987, p. 122). Rahkani also points out that in the courts of Sultan Mahmud and Sultan Mas’ud, depending on the space available, different orchestras were employed: small orchestras in confined spaces and larger orchestras with more and stronger instruments in larger spaces (Rahkani, 1998, p. 238).

During the Timurid Empire, there were various musical ensembles, both for entertainment and military purposes. Many historians note the presence of numerous musicians and martial instruments such as drums, dohol, surna, naqqāra, and barghu in the Timurid court (Delrish & Shateri, 2014, p. 62). Moreover, musicians likely participated in important political and military sessions to create a pleasant atmosphere and convey joy and celebration during significant decisions (Shiran et al, 2020, p. 441). Habibi confirms the longstanding practice of performing epic songs accompanied by wind and percussion instruments among Afghans, noting that during royal processions, announcements of the king, or the return of warriors from battle, the dohol, along with other instruments and songs, was played (Habibi, 1988, p. 620).

Babur, in his Baburnama, repeatedly mentions the presence of musical groups in the court and the use of military music, such as naqqāra ensembles, during warfare (Babur, 2007, pp. 109–167). Vakili Fofelzai also notes naqqāra houses in large cities and towns, writing: “On the nights of celebrations and feasts, in the name of the Shahanshah of the country, the naqqāra of respect would be played to signify obedience. Afterwards, the naqqāra for the commander of each city and province would be played according to rank. If the inhabitants of a region or city disobeyed the order of the sovereign, the designated naqqāra would sound first, signifying rebellion and defiance against the ruling authority. The custom of playing the naqqāra was such that it was played more for the Shahanshah, less for kings, and even less for governors and officials, in sequences of five, four, three, two, and one times. During the Sadozai sultans’ era, in the cities of their empire, the naqqāra of obedience was played in their name and honor. Timur Shah, aware of this grand ceremony, observed the practice during his reign and in major centers played the naqqāra in his own name, and in the name of kings and governors under his protection. During his time, there was a royal naqqāra house in Bala Hisar, Kabul” (1967, p. 384).

From this document, it is evident that music played a significant role in political decision-making and in delineating differences in the political and social positions of individuals within the government. Some historians also describe the tradition of epic singing among Afghans. Epic singing in Afghanistan has a historical background, and whenever Afghans faced foreign invasions, they composed songs akin to ballads. Even today, epics from past eras survive in folk songs, often accompanied by atn dance and drumming. Felston similarly notes epic music and musical ensembles during the Durrani period: “They have songs praising tribal battles and the deeds of elders. Some recite verses from other poets, and some play the ney, kamancheh, surna, and rabab, singing in unison with them” (1994, p. 228).

During the reign of Emir Sher Ali Khan, it was customary to play military music when foreign representatives and guests arrived. Yaroski, in his book on the Russian Tsarist embassy to Emir Sher Ali Khan’s court, mentions Afghan army drummers and trumpeters who escorted the embassy during its journey (1968, p. 55). Based on this, it can be concluded that instruments such as the drum, trumpet, and naqqāra were common in military music during Emir Sher Ali Khan’s era. Although this period did not bring major changes, it holds historical significance as Emir Sher Ali Khan initiated the process of modernization in the country (Jamal, 2019, p. 25).

The use of drums, trumpets, karnās, and naqqāras, in addition to the era of Emir Sher Ali Khan, continued until the reign of Mohammad Zahir Shah; although their presence in the urban environment of Kabul gradually declined. Nevertheless, in many northern regions of the country—including Sar-e Pol, Balkh, Faryab, and Jowzjan—these instruments remained prevalent until recent years, primarily used on special occasions, particularly national and local celebrations. In contrast, another group of traditional instruments, namely the dohol and surna—considered among the most important instruments for festive music in Afghanistan—maintained their prominence and continued to play a central role in collective ceremonies, including weddings and Independence Day celebrations. Prominent performers of these instruments in Kabul largely originated from the “Chahardahi” district and played a significant role in preserving and transmitting popular musical traditions. Danilo, a French researcher who visited Kabul in the 1960s (solar calendar 1340s), describes this group, writing: “The drummers and surna players from Chahardahi perform at wedding ceremonies; they accompany the groom who escorts the bride on horseback” (Danilo, 2003, p. 4). This description indicates that the dohol and surna were not only integral to celebratory rituals but also an inseparable element of the popular culture of Kabul at that time.

Ultimately, it can be stated that loud percussion and wind instruments—including the trumpet, karnā, drum, naqqāra, and dohol—have a long-standing history in Afghan music. Their reflection in historical sources, local rituals, and even the narrative literature of various ethnic groups underscores their prominent status and cultural role in the social life of the people of this land.

Conclusion

A historical review of percussion and wind instruments, especially the drum and trumpet, in Afghan music demonstrates that these instruments were not merely sound-producing tools but vital elements in the social, ritual, and political systems of the region. Archaeological evidence, literary sources, and historical texts indicate that the drum, trumpet, and karnā, from the Vedic and Zoroastrian periods through the Median, Kushan, Pre-Islamic, and Sassanian eras, played crucial roles in issuing military commands, coordinating armies, conducting religious ceremonies, and displaying royal authority. This significance is also reflected in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, which shows that martial and ceremonial music occupied a clear and solid position within the governmental and cultural framework of Afghanistan and neighboring regions.

With the advent of Islam and the passage of time, the functions of these instruments evolved, yet their importance in battles, celebrations, and court ceremonies persisted, reflecting the continuity of musical and cultural traditions in Afghanistan. Examining these instruments reveals that music, beyond its artistic aspects, served as a medium for communication, coordination, and a symbol of political and social power.

Therefore, research on loud percussion and wind instruments in Afghan music not only contributes to a more precise understanding of the country’s musical history but also opens new avenues for exploring the interconnections between music, culture, ritual, and political power throughout history. It can provide a foundation for interdisciplinary studies in history, anthropology, and musicology in the region.

References

Abdumutalibovich Marufjon Ashurov, (2022). Musical life in the Samanid state In the ninth century and Uzback music in the XI-XV centauries. Gospodarka I Innowaje Volume: 22 ISSN: 2545-0573.

Alonzo, Trevier. Jones. (1898). From Babylon to the fall of Rome. Michigan: Review and Herald Publishing Company.

Asari, Mehdi. (2002). The Identity of Iranian National Music and Instruments from the Beginning to Today. Tehran: Dehkhoda Publishing.

Babur Shah, Zahiruddin Mohammad. (2007). Baburnama. Translated by Shafeeqa Yariqin. Kabul: Directorate of Publications, Academy of Sciences.

Delrish, Bushra & Lal Shatri, Mostafa. (2014). Music of the Timurid Era, Based on Miniatures and Historical Accounts. Historical Sciences Research Journal, Fall & Winter 2014, No. 10, pp. 59–78.

Dhanalakshmi Dr. N. (2021). History of Ancient India (From the Earliest Times to 1206 AD). Tamil Nadu Open University.

Durant, William James. (2002). The East: A Calendar of Civilization. Translators: Amirhossein Aryanpour, Ahmad Aram, Askari Pashaei. Tehran: Elm va Farhang Publishing.

Ferdowsi, Abolqasem. (1994). Shahnameh. Edited by Jalal Khaleghi Motlagh. Vol. 4. California & New York: Mazda Publishing.

Ferdowsi, Abolqasem. (2012). Shahnameh. Edited by Mr. Fereydoun Jenidi. Available at: file:///C:/Users/x/Documents/shahnameh.pdf

Felston, Mont Stuart. (1994). Afghans: Place, Culture, and Ethnicity. Translated by Mohammad Asif Fekret. Mashhad: Islamic Research Foundation.

Gardezi, Abu Sa'id Abd al-Hayy. (1984 [1363]). Zayn al-Akhbar: Tarikh Gardezi. Edited by Abd al-Hayy Habibi. Tehran: Dunyā-ye Ketāb Publications.

Ghobar, Mir Gholam Mohammad. (1987). Afghanistan in the Course of History, Volumes 1 & 2. Tehran: Jomhouri Publishing.

Habibi, Abdulhai. (1988). History of Afghanistan after Islam. Tehran: Donyaye Ketab Publishing.

Herodian (1961). 3rd century. "Book 4: Chapter XI". History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus. Translated by Echols, Edward C. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jamal, Ziauddin. (2019). The influence of Turks on Habibullah Han's modernization efforts (1901–1919). Master’s thesis, Institute Department: History, Department of Modern History.

Kehzad, Ahmad Ali. (1946). History of Afghanistan. Kabul: Kabul Press.

Kashmiri, Mohan Lal. (2015). Life of Amir Dost Mohammad Khan. Translated by Seyed Khalilullah Hashemian. USA: Ayeneh Afghanistan Publishing.

Karydaki, Nik. D.. (1939). Nearch, Chris Admiral Of Alexander The Great. Atan: Primary library Othiki Chania.

Lawergren, B. (2003). Oxus trumpets, ca. 2200–1800 BCE: Material overview, usage, societal role, and catalog. Iranica Antiqua, 38, 41–118.

University Press.

Nusservanji, M. (1922). Zoroastrian civilization: From the earliest times to the downfall of the last Zoroastrian empire (651 CE). New York: Oxford University Press.

Nusservanji Dhalla, M. (2007). Zoroastrian civilization. New York: Oxford.

Nikonorov, Valerii P. (2000). The Use of Musical Percussion Instruments in Ancient Eastern Warfare: The Parthian and Middle Asian Evidence. Music Archaeology of Early Metal Ages. Papers from the 1st Symposium of the International Study Group on Music Archaeology at Monastery Michaelstein 18-24 May 1998. Pp 71-81.

Paykar Pamir, Karim. (2017). The Hidden Face of Amir Dost Mohammad Khan in Historical Perspective. Toronto: Danesh Association.

Plutarch. (2008). The Life of Alexander the Great. (J. Dryden, Trans.). New York: Modern Library. (Original work published ancient times).

Rahkani, Rohangiz. (1998). History of Iranian Music. Tehran: Pishro Publishing.

Sheedfar Shila, Asadi Farsani Majid, Arjomand Pirouz. (2014). Study the Reasons of Growth and Flourishing of Music During Sassanid Period. 3-5 February 2014- Istanbul, Turkey Proceedings of INTCESS14- International Conference on Education and Social Sciences Proceedings.

Shirani, Shahbazi-Hosseini Nia, Seyed Mahdi-Maroofi, Aqdam Esmaeil, et al. (2020). Comparative Study of Women’s Status in Musical Gatherings during the Timurid and Safavid Periods Based on Surviving Miniatures. Women in Culture and Art, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 437–462.

Shaharani, Enayatollah. (2009). Instruments and Singing, Vol. 1. Kabul: Beyhaqi Publishing.

Swami, Prajnanananda. (1973). Music of the Nations. Calcutta: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. (Swami, 1973, pp ).

Uwe, Ellerbrock. (2021). The Parthians: The Forgotten Empire. New York: Publisher by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN.

Vakili Fofolzai, Azizuddin. (1967). Timur Shah Durrani, Vol. 2. Kabul: Tarikh Tolna Publishing.

Valerii P. Nikonorov (1998). The Use of Musical Percussions in Ancient Eastern Warfare: Parthian and Central Asian Evidence. In Hickmann, Ellen, Laufs, Ingo & Eichmann, R., Music archaeology of Early Metal Ages: papers from the 1st Symposium of the International Study Group on Music Archaeology at Monastery Michaelstein, 18-24 May, 1998 (Blankenburg, Germany); Orient-ArchŠologie, 7; Studien zur MusikarchŠologie II, Rahden/Westf: Verlag Marie Leidorfe, 2000, p. 71-82.

Xenophon. (2011). The Education of Cyrus. Translated By Henry Graham Dakyns. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd.

Yarosky, J. L. (2010). The Embassies of Tsarist Russia to the Court of Afghanistan. Translated by Abdul Ghafoor Barshna. Kabul: Beyhaqi Publishing.

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.