Gopal Balakrishnan

Bio

Gopal Balakrishnan is a distinguished scholar focused on European intellectual history, political theory, and the evolution of capitalism. His work critically examines modern political systems and their global implications.

Stories (6)

Filter by community

Identity and the Exhaustion of Grand Ideas

Over the past few decades, intellectual life has been shaped by a growing distrust of ambitious theories that once claimed to explain history and society as a whole. The fading influence of the radical projects associated with the 1968 generation produced a more careful and restrained scholarly atmosphere. Many historians and social theorists became skeptical of large narratives and universal categories, preferring limited scope and methodological caution. In Germany, this shift took a distinctive form through the rise of microhistory, an approach that emphasizes close attention to sources, local contexts, and everyday life. Microhistorians sought to revive the craft of traditional historiography while distancing themselves from older positivist assumptions. Their work often challenges broad concepts such as capitalism, industrialization, and the state, treating them as abstractions that obscure rather than clarify lived experience.

By Gopal Balakrishnan2 months ago in Fiction

A German Revolution?

Even before the defeats of the revolutions of 1848, they recognized that the mutually advantageous arrangements between the middle class and an old regime which it sought to reform to its specifications, would make a bourgeois revolution in Germany dependent upon wider political upheavals across Europe- more specifically another revolutionary breakthrough in France bringing a European and perhaps world war in tow. This would be a recapitulation of the sequence that unfolded from 1789 to 1814, but on a far more developed world market basis, one which would put a nascent international proletariat into contention.

By Gopal Balakrishnan6 months ago in Education

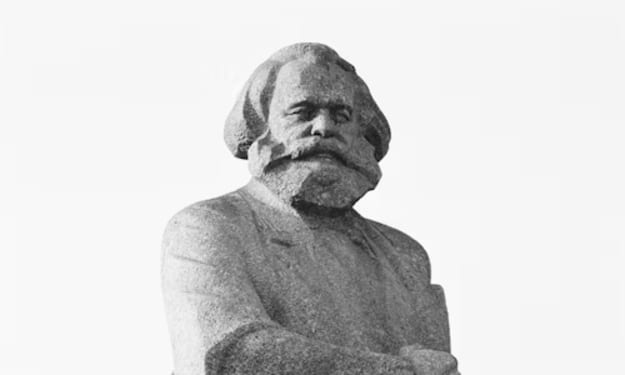

Marx’s Early Critique of Political Economy

Political economy had supplanted philosophy and theology as the primary object of critique. Presupposing an equilibrium of supply and demand, economists sought to explain the economy-wide pattern of relative prices-exchange values-by the same law which governed the class distribution of revenues between landlords, capitalists, and wage laborers. Following Engels, Marx concluded that they were unable to provide a coherent account of the inter-relationship between the economic oppositions within which their theories revolved- cost/price, supply/demand, labor/capital, etc.- because they could not grasp the historically specific dynamic of development that stemmed from the social relations that imposed exchange dependency on producers. In all its variants, the discourse of the wealth of nations presupposed private property in the exchange value form and therefore the distribution of revenues into wages, profit, and rent. Marx noted that it did not, however, explain private property’s historical origins and structural logic of its development. “Economists explain how production takes place in the above-mentioned relations, but what they do not explain is how these relations themselves are produced, that is, the historical movement which gave them birth.” The real order of determination between these categories of political economy could only be adequately grasped in the unity of a self-undermining logic of development that its equilibrium assumptions concealed.

By Gopal Balakrishnan6 months ago in Writers

Marx on the Jewish Question

While in their own idiosyncratic way, some Young Hegelians briefly came to see themselves as Jacobins, the view that Germany was a belated nation condemned to undergo a derivative, ‘catch-up’ revolution was an anathema to them. One could say that they were patriots of a coming two-fold Franco-German republic. While they scorned the mythical Gothic past of the Romantics, they nonetheless all partook in a discourse of national exceptionalism according to which the current generation of German radicals was called upon to make penance for their country’s infamous role in defeating the French Revolution. On this point of honor, they would show their mettle by appropriating and working out the final consequences of the latest advances of Western European thought. The German critique of religious consciousness had adopted the old Voltairean motto écrasez l’infâme and was now eager to expand the war on theology to its political and social corollaries. But repeating the passage from Enlightenment to Revolution was understood to entail transcending the limits of the French Revolution, uprooting the obstacles of religion and atomistic egoism on which it had crashed. Young Hegelian Germany would be the standard bearer of an atheistic revelation, adorned with Saint-Simonian notions of social reconstruction.

By Gopal Balakrishnan6 months ago in Writers

The Hegelians

The development of Hegel’s later philosophy of law must be situated in the context of Prussia’s ‘revolution from above’. After a crushing defeat at Jena in 1806, a group of loyalist officers and bureaucrats initiated a project of sweeping administrative reforms, establishing a new military order, a new university system, an opening for modernist currents in Protestant theology, and beginning the transformation of Junker squires into capitalist landlords. Little more than a decade later, Hegel was inducted into a loose coterie of reformist officials that included Wilhelm von Humboldt and Carl von Clausewitz. In the era of reform, Prussia acquired an enigmatic, dual nature as a self-modernizing old regime, and Hegel’s Philosophy of Right offered philosophical rationales for this German Sonderweg. The project of state-promoted modernization continued after victory over Napoleon, but came to confront ever more determined opposition from two quarters: romantic nationalists who had expected their restored rulers to grant the people more liberties in recognition of their supporting role in driving out the French, and evangelical traditionalists aiming to restore the status quo ante. The argument of The Philosophy of Right was directed at both. After his death in 1831, the fifteen-year heyday of the relationship of the Hegel School to the Prussian State began to break down, as its opponents began to prevail in the struggle for academic placement and official patronage. Hegel’s supporters still had a powerful patron in the Minister for Culture, Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein, but with his death a decade later, their fortunes rapidly began to sink.

By Gopal Balakrishnan6 months ago in Writers

The Critique of Liberalism

In the tumultuous European aftermath of the First World War, the breakthroughs of mass democracy confronted a right-wing backlash that came to adopt anti-status quo pretensions historically identified with the left. The spectacle of industrial warfare was felt to have possessed a higher world-historical significance, cruelly travestied by post-war upsurges of subaltern classes demanding social reforms bordering on Revolution.

By Gopal Balakrishnan6 months ago in Writers