What the Water Takes First

Ophelia, Virginia Woolf, and the Lie of Graceful Drowning

We have always drowned our women beautifully. From Shakespeare's Gertrude speech and Millais' brush, to Virginia Woolf’s stones. We have perfected the art of romanticizing female pain. This is not merely artistic tradition, it is cultural pathology.

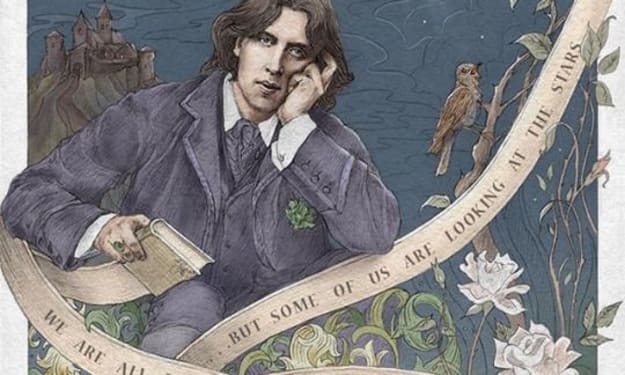

In Hamlet, Ophelia drowns twice, first in the brook, then in the metaphor of Gertude’s speech(Act 4, Scene 7), transforming her “muddy death” into something “mermaid-like” where even the willow bends to frame her as art. Millais’ 1851 Ophelia painting captures the tragedy perfectly. His willow’s gnarled branches both embrace and entrap her, their skeletal shadows contrasting with the luminous gold of her hair, rendering her drowning hauntingly beautiful. It is, in fact, a vision that Elaine Showalter, a feminist critic, condemns as one of those representations that "made female insanity a pretty stimulant to male sensibility" (Representing Ophelia, p. 82). This collaboration between Shakespeare and Millais’ brush exemplifies what Gaston Bachelard called the "Ophelia complex" (Water and Dreams, 1942), in which drowning becomes "the truly feminine death," as water dissolves female suffering into poetry.

Yet for centuries, women have looked at Ophelia and seen not just a character, but a reflection. Why does her death feel like a secret language for our sorrows? Why do we romanticize the very image that reduces us?

We've inherited a vision, that a woman's pain is only legible when it is lovely. That to be drowned is tragic, but to drown beautifully is art.

Virginia Woolf, who on a cold March morning in 1941 weighted her pockets with stones and stepped into the River Ouse. The water took her gently, the way it takes all things that do not struggle. Her husband, Leonard, found her cane abandoned on the bank. In her suicide note, she wrote: "I feel certain I am going mad again… And I shan’t recover this time." Even in death, she was precise, poetic. We remember not the terror of her drowning, but the beauty of her exit. The stones, the river, the cane left behind: a composition as deliberate as a still life.

Still, the Ophelia complex lives on today. Nowadays women film themselves submerged in bathtubs, rose petals drifting like blood in the water. Instagram aesthetics turn depression into a filter: soft focus and muted tones. We have learned to perform sadness in order to seem “interesting” or giving “dark vibes”. We, indeed, are clinging to the lie. Still, we reach for the prettied-up version, the one where suffering looks like art. Because pain is often ugly and meaningless... too terrifying to behold; and if it can be beautiful, then perhaps it can also mean something.

No one drowns beautifully.

The truth is in the body’s rebellion. The body does not want to die. Lungs scream for air even when the mind has given up. The truth is in Virginia Woolf’s stones, which did not carry her gently and grant her peace, but dragged her under in a blind panic of cold and dark.

We keep painting Ophelia floating because we cannot bear to paint her fighting. We prefer the mermaid to the woman because dead girls make better metaphors. “The only quiet woman is a dead one” says Sylvia Plath. They never grow old, never get angry, never rewrite the ending.

About the Creator

Yasmine Lagras

creative writer , poet and researcher.

Aspiring to reach more people.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.