Villa Schifanoia, Graduate School of Fine Arts

An American School in Florence, Italy

Mark Twain had two false starts in writing his autobiography. Both times he tried to set the events of his life out in chronological order, and both times he found the results false, and could not bear them. Then he took another tack. He allowed the events of the day to trigger memories, and he wrote about those memories, not ordering his work by the chronology of his life, but by the happenstance of what came up for him on that day, whether he read it in a newspaper, or came across it otherwise.

I have no plans to write an autobiography, but this morning I feel I understand the cleverness of his method, because I have just read a news story that brings memories flooding back. The Tuscan Villa Palmieri is for sale and in the news today. Florence is surrounded by hill towns, the best known of which are Settignano (where Mark Twain stayed in a villa) and Fiesole, where the Villa Palmieri is. That villa, and several houses in Fiesole, look down on Piazza San Domenico in Florence, a small neighbourhood at the edge of the city, where I stayed while studying music there. My school, a Florentine campus of an American school, was just down the street from Piazza San Domenico, in the Villa Schifanoia. Actually the panorama from Fiesole is very impressive. The whole city is spread out before you, and and sunset I often climbed up the hill to watch the torches being lit on the top of the Palazzo Vecchio.

My year at Villa Schifanoia was 1975-76. "Noia" means bother, or maybe better "ennui." "Schifa" is slang for avoid, so the villa to avoid ennui. Its home institution was Rosary College, a private, Catholic university in River Forest, Illinois, today named Dominican University. It offered master's degrees in fine arts: music, visual arts, and art restoration, the last of which had to be closed because the Florentine teachers of art restoration allowed much more to be added to a canvas than an American professor would ever have imagined.

The students were there not because of their religious affiliation, but because of the chance to study in Italy. The lira was trading at about five hundred to the American dollar. I spent roughly 800 Canadian dollars all told for the academic year there, less than I would have spent living at home.

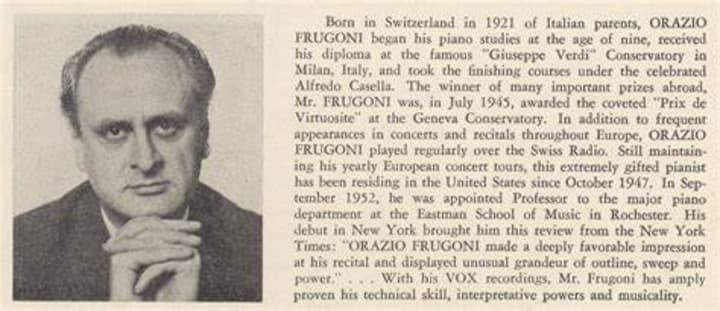

The year did a lot for me. It opened my eyes to European culture and history, forced me to learn Italian, which I used extensively later, and gave me access to the teaching of a retired piano recitalist, one who had recorded over 50 albums, Orazio Frugoni. He had retired from teaching at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester to return to his home country. What an opportunity!

I remember many of the students, especially the pianists. Two of them, Ralph Neiweem and Claire Aebersold, went on to become a prominent piano duo in Chicago, also teachers there, and founders of a well known piano duo festival. They can frequently be heard live or on the radio. I knew one of the painters very well, and I have seen her name attached to exhibitions and schools over the years. I don't remember the name of her painting instructor, but she was a niece of the composer Ravel. That is how the musicians thought of that art prof.

The grounds had persimmon trees which, at a certain time in the fall, provided us with all the sweet fruit we could handle. There were also olive trees and cypress. I remember that two of the art students had radically different interpretations of the cypress trees. One said they reminded her of giant asparagus stalks, and the other said they looked as though they were pointing up to God. Both girls admitted they had ruined cypress trees for each other.

Near the beginning of the year, the Dominican sisters who administered the school took us all on a bus tour of San Geminiano, the "Romeo and Juliet" town.

Classes of previous years had been taken to Rome for a papal audience. The sisters decided that our collective comportment did not merit such a privilege or make an encounter with His Holiness advisable. They were probably right about that.

When I met Frugoni he had taught at Eastman for 20 years and in Florence for seven more. He had mentored so many students that he had comparisons for all of us. I was younger than the others. I reminded him of one of his students who became a conductor at The Met. He thought my career would be in music but not in piano performance, and ultimately he was right (I am a musicologist). The student recitals were exciting, and they were all different from one another. He did not want his students to conform to any particular style.

One morning a week I dedicated to the museums of Florence. What treasures! Florence is very different than Rome. The latter, the "Eternal City" has so many layers of history. Florence is mainly a place to study the Renaissance, and in that period the city is very rich in art. The biggest music festival was the Maggio musicale, musical May. It was especially good for twentieth-century music and new music.

At the end of our year there was an opera workshop, featuring the retired singer Tito Gobbi. The whole school somehow became more glamorous, more operatic in short. Besides the aspiring young professional singers there were pianists from a special accompanying program in Vienna. Those kids could play the piano accompaniment to just about any Italian aria in any key you cared to name. Often Gobbi would say, "Try it a tone higher," and they would oblige on the spot. They were impressive, especially to me, because I was a terrible sight reader. I understood the principle, read a bar or two ahead of what you are playing, but I couldn't manage to do that.

The Saturday before my flight back to Canada, one of the singers, Wolfgang Lenz, a towering baritone, burst into my practice room. He said he wanted me to accompany him the next morning in a practice room. I said he had me confused. He wanted one of the professional accompanists. He said no, he was sure he wanted me. At length I gave up arguing and agreed to meet him in the large practice room Sunday morning.

When I got there I was shocked. The room had more than twenty listeners. He whispered to me that he wanted to move his career forward, that these German impresarios and respected teachers could get him opera roles. I started to shake and looked for a trap door. He handed me my part for what he wanted to sing: the king's aria "S'el serto real" from the opera Don Carlo. It is a wonderfully rhetorical aria for the bass, a sea of black note tremolos for the pianist. I was ready to faint. Of course I had never played that music. Then he said he would stand on my left, with me between himself and the audience, and could I be sure to bring his part out because he was still learning the aria?!!!

Well at age 19 I did not have the sense to bolt from the room, but I felt like it. We started the aria. His voice boomed in my left ear deafeningly, which was good because I did not hear the high-pitched sounds of anxiety tormenting my head. Strangely, inexplicably, I pulled it off. To this day I do not know how. The senior impresario said something like we performed very well together considering we had not known each other long. I thought if she only knew....

So out of all the lessons I learned in that time, this was perhaps the most important. Never say you can't because maybe you can. As one of my friends says simply, "Never give up."

Years later I went back to Italy, every summer for years, in a longterm, tough archival project, reading documents at top speed in Italian and in chicken-scratch Latin. And over the years I did not give up, and I found, and found, and found, until my findings changed our understanding of music in Italy in the fifteenth century. Thank you Villa Schifanoia, and never give up.

About the Creator

Paul A. Merkley

Mental traveller. Idealist. Try to be low-key but sometimes hothead. Curious George. "Ardent desire is the squire of the heart." Love Tolkien, Cinephile. Awards ASCAP, Royal Society. Music as Brain Fitness: www.musicandmemoryjunction.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.