Jim Sloan

The Painter Who'd Rather Catch Snakes

By Brian D’Ambrosio

At 90, Jim Sloan has lived several lifetimes’ worth of work—carpenter, sign painter, excavator, sawmiller, road-builder and the go-to rattlesnake remover of Galisteo, New Mexico. Art may be the through-line, but it has never been the source of his income, nor the center of his universe. Sloan has always kept one foot in the studio and the other in the soil, without bothering to decide which world he truly belongs to. The truth is that he fits cleanly into neither, and he has long since stopped trying.

Sloan built his livelihood with his hands—driving nails, operating heavy machinery, painting houses, digging septic systems, grading driveways, and reshaping raw earth. “Construction was obvious for me,” he said. “I had to make a living, but I also wanted time to paint. The trades let me do both.”

After years in California, apprenticeships, union cards, and eventually mastering big equipment, Sloan learned to earn enough in short bursts to carve out the solitude he needed for painting. The physical fatigue never deterred him.

“People compartmentalize: Either you work or you make art,” he said. “For me, they were always connected. Building things, moving earth—it was creative, not drudgery.”

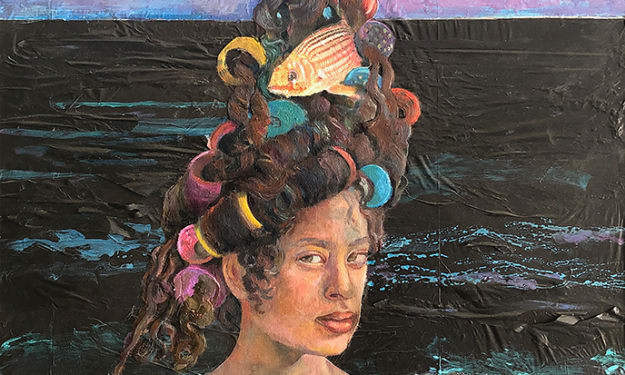

For decades he kept two small studios, one in an adobe outbuilding in Galisteo and another in Cedarvale, New Mexico. Today, the garage of his Galisteo home is stacked floor-to-ceiling with portraits: A local man who froze to death in his own home. A beloved waitress trapped in a stalled life, depicted with a dignity she never recognized in herself. An obscure writer butchered for speaking truth. The imprisoned Russian dissident Alexei Navalny. A potter named Priscilla Hoback wearing her trademark bonnet.

The work is personal, offbeat, and uncommercial in the cleanest sense. It looks homespun at first glance but carries a visionary charge—figurative abstraction intertwined with references that only a painter’s painter might catch.

“My art is all there—who you knew, who you admired, what you’re seeing, what you’re internalizing,” he said.

In the broader art world, Sloan has carried a host of labels—untrained, self-directed, renegade, off-trail. The designations don’t bother him. One visitor called him an “outlier,” and Sloan shrugged: No reason to argue with him.

What the gallery system calls him matters even less, he says. During a recent two-day opening, he only sold a single small painting for $25. “But I’m happy. All I need is a studio and a hot plate.”

Painting, to Sloan, is a language that’s older, deeper, and more honest than writing. “The first people to write things were painters,” he said. “When the cave painters went in, they couldn’t bring sketchbooks or cameras. They took ideas. That’s what I try to do—make images of ideas.”

As a boy, he studied painting in Japan, where the connection between brushwork and written language shaped him permanently. Calligraphy as architecture. Characters derived from pictures. A worldview where art is not decoration but communication. “Now we’re so removed from that,” he said. “People spend 20 seconds looking at a painting: ‘Oh, that’s a tree.’ And then they move on.”

Similar to art, when he talks about snakes, he lights up with boyish joy.

“It was a slow year for snake catching,” he said of Galisteo. “Only about 40.”

Residents call him whenever a rattlesnake appears on a porch or near a dog’s water bowl. Sloan arrives, calm and amused, and moves the snake without harming it. He never takes money.

“People say I’m doing a great service. But really, I’m the beneficiary. I love snakes. With 200 people here calling me every time they see one, it opens up a whole world.”

He has pulled rattlesnakes out of bathrooms, from behind woodpiles, from areas where they’d wandered indoors hunting rodents. “They’re beneficial,” he said. “Rattlesnakes take care of rats, which can kill anything.”

He shares stories of rear-fanged species, of herpetologists fatally bitten while probing a specimen, of frogs kicking their way back out of a snake’s jaws in a last attempt at survival. Sloan speaks of snakes with the same intuitive clarity he applies to brushwork—no fear, no mystique, only understanding.

Born in Chicago in the years leading up to World War II, Sloan spent his childhood in motion. His father, a Navy radar technician, was sent wherever top-secret technology was being installed—an island in Maine, then Brooklyn after the Germans captured a British ship and learned the radar system. When the war ended, the family followed his father to occupation-era Japan. Sloan was 10.

He studied painting, absorbed a culture that treated art as literacy, and internalized a sense of environment that he never lost.

“In Japan, everything blends into the landscape,” he recalled. “You come back to America, the fog lifts over San Francisco, and everything is bright white, sticking out like a sore thumb.”

It made him determined to build his own surroundings—studios, spaces, atmospheres that supported the work.

At 90, he talks about art and snakes and machinery with the same intensity of someone beginning a career, not ending one.

What he has always maintained, quietly and without fuss, is independence — from the gallery world, from labels, from academic definitions of art. From fear. From the urge to conform.

“My art is ideas,” he said simply. “Everything else is just the world happening around you.”

Brian D'Ambrosio is the author of New Mexico Eccentrics.

About the Creator

Brian D'Ambrosio

Brian D'Ambrosio is a seasoned journalist and poet, writing for numerous publications, including for a trove of music publications. He is intently at work on a number of future books. He may be reached at [email protected]

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.