It was about 4:30 p.m. on a Tuesday in February when I got the call confirming I had cancer. I was in the bathroom at work when I answered the phone. Upon hearing the doctor gently say, “I’m sorry, you have colon cancer,” I started blushing. I saw myself redden in the mirror and felt warmth spread through my body until it landed around my knees, which were about to buckle.

That call was the first of many for check ups and tests. For my first appointment with a surgical oncologist, I took my friend Julie. Julie was exactly the type of person one should take with to the doctor’s: she wasan occupational therapist, completely unfazed by doctors, hospitals or medical terminology.

We faced the surgeon who sat behind an imposing desk. Though I had my notebook and pen ready, I was in a daze. He started talking and I immediately fixated on the anatomical models of the colon and lower intestines he had on his desk. I also noted a big box of All-Bran cereal on his bookshelf.

I snapped to attention when I heard him say, “judging from where the tumour is, you will undoubtedly have to wear an ostomy bag.” My mind flashed back to a memory from São Paulo, Brazil. I was on the subway when I saw a man move slowly down the subway car. He stopped to lift up his shirt to commuters and then put his hand out to ask for money. It was only when he was in front of me that I saw he was lifting his shirt up to reveal a half-full colostomy bag. It was transparent and full of stool. I immediately put my head down, but the image had already seared itself in my brain.

I was still lost in thought until the doctor asked if I had a good support system. “Cancer is really tough, and you’re going to need family to support you.” Well, there it was. The question I had been dreading. My eyes welled up with tears. I had no partner, my mother was dead, my father had advanced dementia, and I was permanently estranged from my sibling. I had been in therapy for years trying to overcome a painful childhood full of emotional and verbal abuse.

I struggled with self-love; I didn’t get it. I argued often with my therapist: “What does self-love even mean, or look like? If I’ve never genuinely experienced love, how do I teach myself what it is?

After the appointment, I cried and held onto Julie. My friends were my family. I didn’t have many, but that’s where I was going to start.

The news from the tests was positive: the cancer had not metastasized. I didn’t need chemo or radiation, but I did need to wear a bag.

A few days before my surgery, I met with a wound and ostomy nurse who was bubbly and kind. She gave me literature and supplies: protective rings, a measuring card, a pouch, flanges, scissors, tape. “Do you have insurance?” she asked. I did not. “Ostomy supplies can get expensive,” she whispered, “but we’ll see what we can do to help.”

After my 9 hour surgery, I came to. My throat was sore from the intubation and I was woozy. I looked down at my torso and slowly began to understand my new life.

To the left of the large gauze pad just above my belly button was a clear ostomy bag that looked like it was half-full of brewed coffee. I didn’t have to worry about changing it just yet; nurses changed it for me. I focused on getting up and walking around as I was told this was the quickest way to build strength and get discharged. My routine was to eat the bland food that was brought to me, feel the bag begin to fill up and then walk around the unit before heading back to bed.

On the third day, my surgeon visited. He said I was almost ready to be released but needed to know how to care for my stoma.

The dietitian advised me to eat soft, white foods: white bread, pasta, croissants, Gatorade, potato chips. I couldn’t quite believe it; it seemed too amazing to be real.

Finally the ostomy nurse came in. We went into the bathroom with the ostomy supplies. I sat on the toilet as she instructed me to first peel off the bag. I saw my stoma poking out of my abdomen: It was red, moist, floppy and covered in stool. I didn’t recoil from it. I felt protective of it; here it was on the outside of my body when it should have been inside protected by muscles. This little stoma; it must have been terrified.

Following her instructions, I cleaned around the wound with saline. Stool fell out of my weird little spout. “It’s okay,” I whispered. Next, I measured the stoma, cut the hole in the flange, warmed the waxy protective ring in my hands before stretching it and then firmly placing it around the stoma. Then I pressed the flange on top of the sticky ring and clipped my bag on. There were a lot of steps but I was eager to leave, so I reassured the nurse I could manage.

Finally, the surgeon said I would need to measure my “output” every time I emptied my bag to ensure the consistency wasn’t too watery. “You want it to look like oatmeal,” he said.

The next day, I left the hospital. Still unsure of all the steps involved in caring for my stoma, I watched videos on YouTube. I was floored. Teenagers with diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease and colon cancer, all matter-of-factly explained how they changed their stoma bags. If they can do it, so can I. I also learned that naming stomas was common. I decided to call mine Julia.

Naming her shifted something in me. I saw my weird little spout as a helper, a being. Julia was lost, separated from her home inside my body and living outside to help me heal. She was a vulnerable piece of me that needed care.

As I was learning to take care of Julia, there were accidents. Sometimes she fell off during the night and I would have to get up, strip my sheets and change her. Or sometimes I would eat the wrong thing and my output was too liquid. When things like this happened, I spoke lovingly to her, “it’s okay, my love. It’s okay. I’m going to change you and we’ll just try again.”

Was this self-love? I had never talked to myself so kindly before; it certainly felt like I was onto something.

Julia and I were together for almost a year. I cleaned her, dressed her ostomy bag in silk covers, put her in a special belt when I had sex or went swimming. I laughed when she made my bag puff up with air. “Someone’s gassy!” I would tease her. Then I casually took her into the bathroom to deflate my bag.

I won’t pretend I unravelled the secret of self-love. It ebbs and flows, but this stoma, Julia, helped me treat myself with kindness. She reminded me that my body is amazing and strong and deserves care.

She’s on the inside now, but I still talk to her lovingly. I pat the scar on my torso and think of my sweet little visitor who taught me so much and whom I had the amazing pleasure to meet.

About the Creator

Daphne Faye

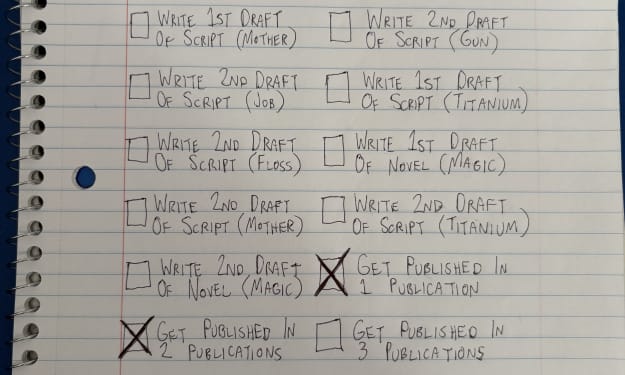

I love to write personal essays. Some are humorous; others are more serious, but they're always heartfelt. I'm also an avid photographer, check me out on Instagram @molelovesbokeh

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (2)

Hi there Daphne, I have come to you via Vocal + Assist. Subscribed and hearted. Thank you for sharing with your story. I’m so sorry about you bowel cancer (I am breast cancer surviror but all is well now.) I loved the way you spoke of your struggles with self kindness and self love. Though no doubt not the path you wanted but it seem Julie helped you find what you were searching for. Pauline 🌸

What a powerful telling of your story! I'm glad you and Julia have been through a healing process and are "reunited" now❣️ x