Vikings, speedboats, abject poverty and somewhere in Syria

It has to be Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire

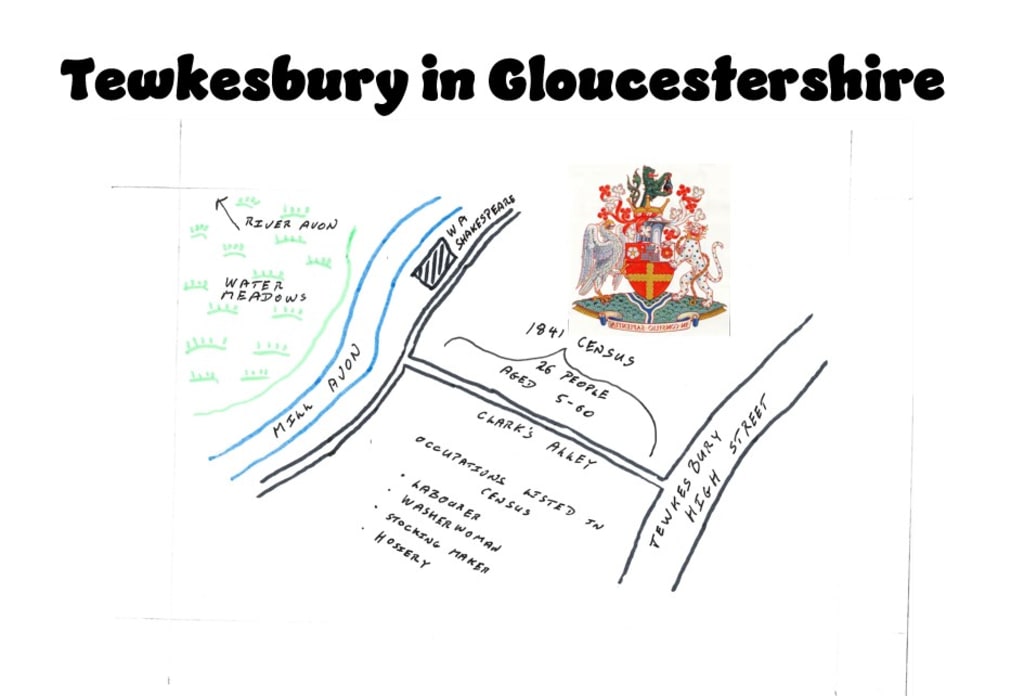

My coddiwomple* around Tewkesbury began along a narrow lane called ‘Back of Avon’ which hugs the town side bank of the ‘Mill Avon’, not the River Avon proper which meanders through some water meadows a little further out of town.

This channel of water was estimated to have been cut in the 12th Century to power the mills of the town by diverting some of the River Avon’s flow. In the 15th century it became a line of defence against marauding Vikings attacking the town who had the temerity to pillage, loot and terrorise the town. If the water meadow between Mill Avon and the Avon River didn’t stop them then this channel would have been the last line of protection. for the estimated 1,100 inhabitants.

Soon while walking along this narrow lane, I came across a cream coloured two-story building that is on a patch of land between the lane and Mill Avon. The iron staircase that climbed up the side of this building was festooned with balloons that were flopping in the breeze. At least they were flopping in some warm sunshine unlike the UKIP balloons in Stevenage back in April 2015. From what I could see each of the balloons had a single letter emblazoned on them. Some of the balloons were deflated, saggy and did their best to hide their allotted letter in their folds. Those that remained fully pumped and proud of their letters spelt ‘HPYBTDY’.

On the side of the house was a brown board with faded yellow lettering at the top that spelt ‘W A Shakespeare’. As I was not too far from Stratford Upon Avon I thought this house might have some connection with the great bard.

The sign dispelled that thought. It explained that W A Shakespeare designed and built high performance speedboats in the workshop on the ground floor of the building I was standing next to.

Shakespeare’s claim to fame and justification for the board was that two of his speedboats featured in a canal scene in Amsterdam in the 1970’s movie ‘Puppet on a Chain 2’. The hero’s speedboat, a thirteen and a half foot long Shakespeare Sportsman ski boat, appears in the film in a vibrant daffodil yellow livery. Perhaps there was some paint left over and it had been used up painting this building. Maybe that could explain why this tired looking building was a pale and age ravaged shade of the famous boat’s original livery?

In the film sequence the hero chases the villain who is piloting a white speed boat. This was well before digital photography and CGI. The two pilots really did let rip with their respective boats along Amsterdam’s normally sedate canals.

There was some really uncareful editing in the film. The villain wore a white suit and a white hat that was the result of a Stetson copulating with a fedora in the dark storeroom of a milliner’s workshop. The result was a ‘stetdora’. The brim of this hat, like the balloons on the staircase, would flop around in the slightest breeze. So, in theory on a speedboat going at full chat it would be gyrating vigorously. Not once in the close ups of the villain did this brim flop unlike the hair of the hero. The actor playing the villain obviously could not be trusted to drive a real boat.

Sadly, W A Shakespeare died in 1971 on Lake Windermere in the Lake District testing one of his designs just after the movie was completed. The boat yard appears to have been in a commercial form of coma ever since.

Opposite the boatyard was an entrance to a narrow lane called ‘Clarks Alley’. Its widest point was no more than four feet wide. Its surface is cobbled. Spaced evenly apart were strips of cobbles laid across the run of the lane raised about half a cobbles height to make a shallow ridge. In other places I have been lucky enough to visit this pattern of cobbling laid to give horses pulling carts something to grip on, but this lane was too narrow for a horse to pass through. The walls that faced on to the lane were painted white and where some of the original buildings had been demolished sunlight flooded in and illuminated the floral gardens of the quintessentially English cottages.

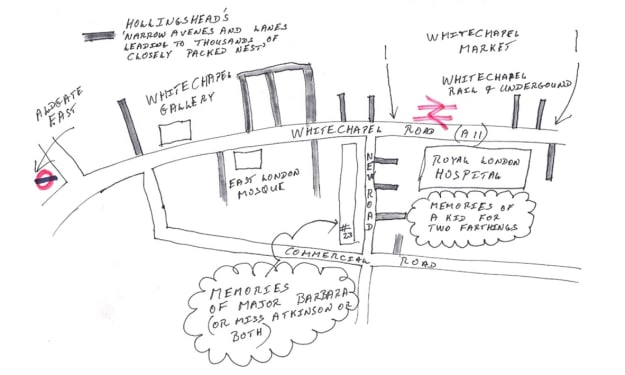

This was not how it had always been. Originally this lane would have been the conduit between two rows of tenement style buildings. None of them would have been more than ten feet wide and all of them would have been two or three stories high that would have blocked out the sunlight. They were not built for single family occupancy like the houses facing on to the High Street. The cutting through of these lanes was an early form of urban back development. Their sole objective was to house as many people as possible who had either been born in the town or had come in from the country hoping for a better life than they could achieve on the land. Usually, the allocation of space was one family per room. A family in the late 18th and well into the 19th century could be two adults with four or five children. There was no drainage or running water so conditions in this man made canyon of misery would have been unimaginably squalid and fetid.

The 1841 Census recorded that twenty six people lived in this lane. Their ages ranged from five to sixty years old. Amongst the occupations declared were labourer, washerwoman, stocking maker, housewife and hosiery. Not many of the adults had occupations next to their name so it has to be a reasonable assumption that those listed as such of working age were at the time of the census unemployed. Sadly, in 1841 it was the majority of these people that made up the twenty six residents.

The cobbled lane I was exploring was once the splat landing zone for various bodily wastes. In Paris the precursing cry for these types of splats was ‘Prenez Garde a l eau’. In Edinburgh, where there was a greater economy with words, it used to be ‘Gardyloo’. I wonder what the cry would have been in Tewkesbury.

In 1841 an inspector from the Board of Health wrote ‘The town’s population was stationary, the mortality rate unusually high and the sanitary conditions appalling’. This was twenty years before Hollingshead wrote ‘Ragged London’ about living conditions there. Two very similar descriptions twenty years and over 120 miles apart showing that very little, if anything, had been enacted to improve the lot of the poor anywhere across the country.

By now I had worked out the reason for the ridges. They were about the length of a step apart and were put there to provide some grip for people having to walk, if not wade, through the raw wastes and effluents being sloshed out of the overcrowded rooms on either side.

Only a few steps using the ridges as markers, and I was on the High Street. A wide thoroughfare lined on either side with shops and banks. Looking above the street level fronts which alter with every change in High Street conditions, you see the architectural history of the town. Exposed beams, brickwork telling the observant that this place has been an active town for a long time with its origins going back as far as the 12th century when the famous Tewkesbury Abbey was built.

One of the products the town was and is still famous for is its mustard. What better way to have this product advertised by another Shakespeare, the great bard himself, William without a second name beginning with an ‘A’. In Henry IV, Part 2 Falstaff has the line “his wit’s as thick as Tewkesbury mustard” when he is describing his friend Ned Poins. Fortunately, Coleman’s, the famous British mustard maker, was not in business in the very late 16th Century when the play was written. Otherwise, Falstaff’s line would not have sounded so piquant:

‘…his wit’s as thick as Coleman’s mustard.’

The making of mustard in Tewkesbury is a part of a culinary continuum that has been arcing across humanity’s tastebuds for close on 11,000 years. As scarce as archaeological evidence is about how we accepted mustard as part of our diet; traces of it were found in a place named ‘Jerf al Ahmar’ in the ‘fertile crescent’ of northern Syria.

I searched the High Street for some mustard balls or even some jars but without success. There wasn’t even any for sale in the town museum. I did get some, via online shopping. It certainly was different from Dijon or English and almost as sweet as that sold as American mustard. Honestly, the unique blend of horseradish in Tewkesbury mustard gives it an individual and complementary blend of sweetness and heat. It is quite aromatic as well affording the citizens of 18th and 19th century Tewkesbury some relief from the fetid stenches of the narrow lanes only feet from the main thoroughfare of trade commerce and prosperity.

* Coddiwomple - to wander purposefully but without any fixed destination. It is the title I have chosen for a book I am preparing which is a collection of short pieces about my travels around the UK.

About the Creator

Alan Russell

When you read my words they may not be perfect but I hope they:

1. Engage you

2. Entertain you

3. At least make you smile (Omar's Diaries) or

4. Think about this crazy world we live in and

5. Never accept anything at face value

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.