The air in the forest is thick with rain and mosquitoes. Everything hums. Cicadas so loud you feel their vibrations in your chest, rattling your ribcage. You can’t sleep. The heat is a wet blanket over your face, clinging to your body. When your mother calls to you from the other room she sounds like an animal yelping in pain. You already know what is happening. It is past midnight and moonlight casts shadows across the floor. They remind you of ghosts. Rain hammers against the tin roof, pours through the hole in your ceiling, collecting in a pool near the door. She calls again – not words – just the sound of pain. Her voice cuts through the rain and the cicadas and the sound of your own heart pounding in your ears. You gather yourself for a moment – your breath catches like a bug in your throat. You rise, padding barefooted across the room. You step in the puddle. The water is warm. It feels viscous, like mud. You don’t turn the lights on. The kitchen looks two dimensional in the moonlight – a watercolour painting. For a second you stand there to check if you’re dreaming. Count your fingers. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. She calls again. You wonder if there is time to call an ambulance. Count your breath. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. You go to her.

Her room is aglow with soft yellow light. Moths gather around the lamp in the corner, their bodies thudding rhythmically against the shade. You stand in the doorway. Your mother is bent over next to the bed. Her hair clings to the sweat on her face. You can see the pain coursing through her body – she is gasping – clutching at every breath like the summer air is analgesic. Her pregnant belly swells under the pale blue of her nightgown. Your body is a dead weight. You can’t move. Towels, your mother groans. Towels. You ask your legs to carry you to the bathroom. You feel them moving without you – feel your hands reaching into the cupboard under the sink – gathering as many towels as you can carry. You bring them to her bedroom. She is half squatting now, her left-hand clinging to the bedside table. You can see all the veins pressing up through the skin on the back of her hand. You stand again in the doorway, holding the towels to your chest.

There is a moment, then, when everything stops. A break in the rain – a sliver of piercing quiet. Your mother stops groaning. She pushes herself up against the force of her pain and, for a breath, she holds herself steady. She looks into your face – eyes like tourmaline crystal. There is kind of startling magic about her – about the way her body holds the body of your little brother – no longer an idea but a person pulled into existence through this impossible process of breath and pain and breath and pain and then – explosively – life.

He’s coming now, she says. Her voice is low and steady. I want you to call the ambulance. They won’t be here ‘til afterwards. But it’s okay. It’s okay. We’re going to be okay. He’s going to be okay.

She smiles at you.

I love you Mum, you whisper.

You hold her eyes with your own and you realise you are crying. Your mind pulls memories up from a dark place – they course through you – all these iterations of your mother’s survival. You see her in the bath, storm-coloured bruises spreading against the gentle cage of her ribs. You see her two dimensional, standing inside a mirror, stamping makeup onto the blackened skin around her eyes. You hear her cry out in pain when he kicks her in the shin with his steel-capped boot. You see her in the watery morning light, limping around the kitchen, packing fruit into your lunchbox. You see the way your stepfather’s violence marked her body like it was just a thing to be owned – a thing to inflict other things onto – a thing without a person inside. Still – through this violence – life grew inside the body of your mother. Still – through this violence – your mother found courage nestled in the base of her throat enough to tell him to leave.

Now, you think, this pain of childbirth is different to the pain he caused in her body. It belongs to her. She braces herself against it with grace. There is a necessity to it – this pain in the absence of violence. This pain that is mixed with the salve of a mother’s quiet love for her children. You are struck by the strength of her – startled by the presence of pain that is productive – purposeful – full of newness and hope. It feels like a punch to the chest. It feels like a seed that will sprout into your own womanhood. A lesson in how to survive – how to hold pain in your body and transform it into love. You realise that you came from the same kind of pain. You think about your own birth – twelve years ago now. You were born early – unwombed too early – a humidicribbed creature kept alive at the hospital while your mother went home to the terrible absence of baby. You would not exist without the pain of your mother.

You are breathless – then –

A gust of tepid wind shudders through the house – through your body. It dislodges the memories, and you are left blinking the ghosts of them from the surface of your eyes. Your mother is no longer smiling. Her breath is quick and shallow. Her body seems to you like a vessel for a kind of knowledge only bodies understand. The kind of knowledge that lives in your guts instead of your brain. Somehow, her body knows how to have this baby.

It starts to rain again – so heavy it sounds like stones smashing against the roof. The moths are frenetic – a halo of movement above the lamp. The shadows of their bodies move across your mother’s face. Light and dark strobe against her skin. You are still in the doorway clutching towels to your chest. Your mother groans, breathes, groans again. You can see the way pain gathers and falls inside her – waxing and waning. It is cyclic. The cycles grow shorter and shorter until there is no relief. Your mother seems suddenly so full of pain that it has melded with the thingness of her own selfhood.

You realise you have not called the ambulance. You realise you have dropped the towels in a pile at your feet. Your body seems like an object you are trying to move with telekinesis. You feel like a child staring at a pencil, willing it to move across the room. You plead again with your legs to carry you to the kitchen and then you are moving through the house, somehow disconnected from the actions of yourself. You still don’t turn on the lights. The buttons on the phone glow neon green. You dial triple zero. It feels mechanical. You ask for the ambulance. When you speak, your voice seems to come from somewhere outside of your own head. My mum is having a baby. You have to yell over the rain. No, I mean she’s having him now. We live in the bush. It’s a long drive. She can’t talk. He wasn’t meant to come for another two weeks so I guess he’s kind of early and I think she’s ok but she’s in a lot of pain and –

He’s here

You hear her shouting over the rain. He’s here, he’s okay, he’s here.

You repeat this to the woman on the phone. He’s here. She asks you if he is breathing. I don’t know, you say, I’m in the other room. Your mother calls again. Without thinking, you hang up the phone. You run back through the house to her bedroom.

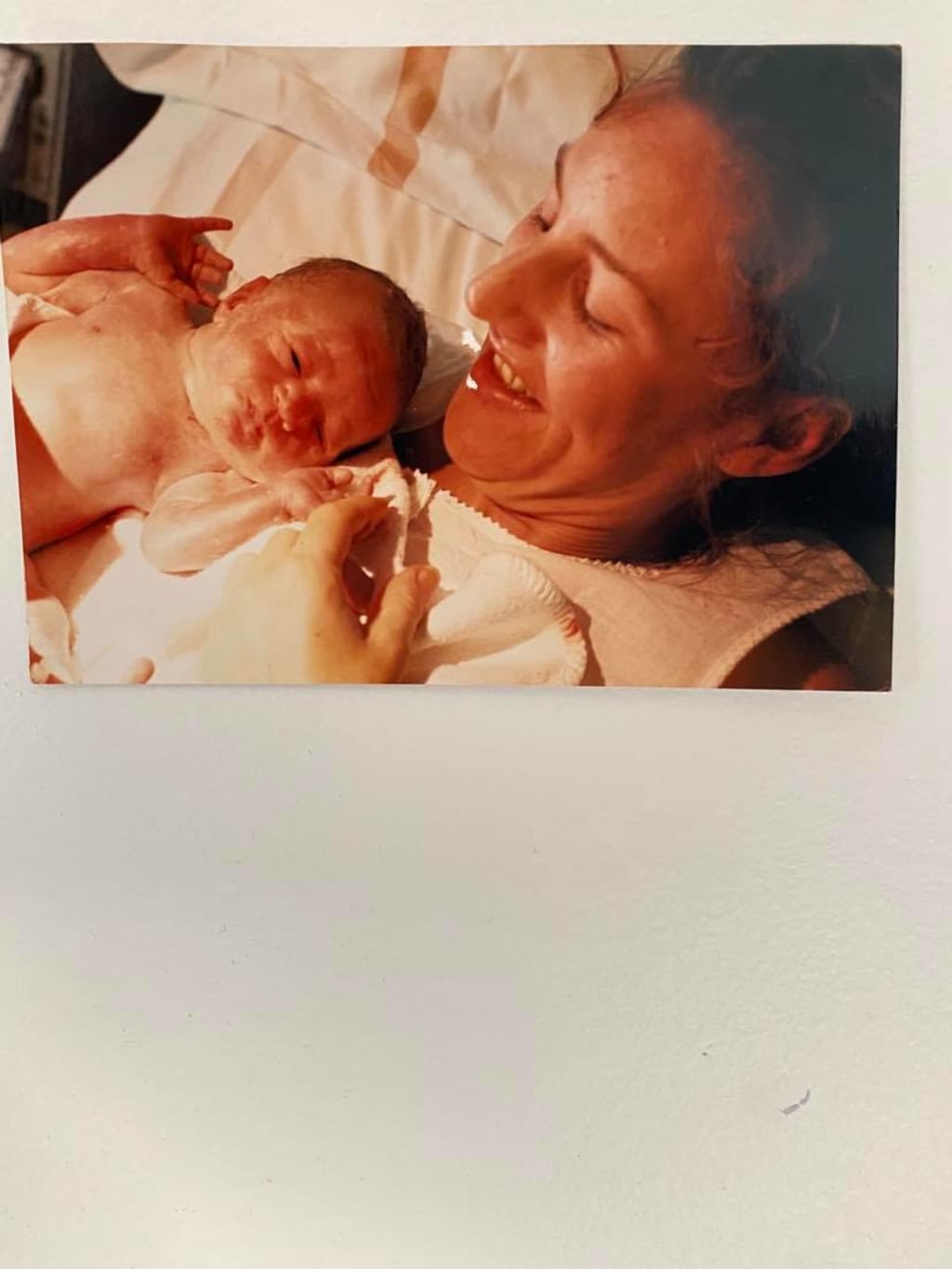

She is sitting on the edge of her bed now, rocking gently back and forth. There is a buttery calmness about her – a kind of settling. She holds him – this tiny, wrinkled creature – up against her chest. For a moment, terror grabs at the base of your throat. You worry that he hasn’t cried yet – hasn’t taken the world up into his lungs and held it there for a moment. You worry he isn’t breathing. Your love for him turns sharp and desperate, so when you hear his tiny voice cry out for the first time, it feels like medicine. Your insides turn gooey. You sit down on the bed next to your mother. You look at your little brother’s face and the world falls to pieces.

He’s beautiful, you hear yourself saying. He’s beautiful.

The three of you are crying now – alone in your little house in the dense forest – the air still cacophonous with rain and cicadas. You realise this moment will become a memory you cherish like a precious stone – a thing you will use as a balm for the wounds of your future. There is something secret about the things you have learnt from the birth of your brother. Something you will always struggle to put into words – the way pain can be necessary and not necessarily violent. The power of your mother’s survival and the way her body loved your brother into being – through everything –

the strength and resiliency of womanhood.

About the Creator

Erica Williams

A writery human from Melbourne with a penchant for self indulgent memoir, sad girl poetry, and sometimes the odd bit of off-kilter fiction

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.