Women of Kokoda

Untold histories of women touched by war in Papua New Guinea

I grew up in Australia, and was 7 years old when Paul Keating drew our attention to the importance of our army's efforts at Kokoda. As I grew older, I became more aware of my own family's connections to the Pacific, and heard every now and again a mention of my great-aunt Consie going to Papua New Guinea during World War Two as a nurse.

I look back now and admire Keating for his commitment to changing the way that Australians saw themselves, and their place in the region. His Redfern Speech was another iteration of this, I felt, in line with other efforts to acknowledged the place of First Nations peoples in our country, including Gough Whitlam's gesture of passing land back to Vincent Lingiari at Wave Hill. However, there is still so much historical research that can be done to fully comprehend the extent of the impact of the Second World War on Papua New Guineans, both at the time and since. I have worked with a team of Australian and Papua New Guinean researchers, led by Dr Jonathan Ritchie, since 2014 to collate and curate memories of war from Papua New Guinean perspectives, and if I have gained nothing else, it is an appreciation of how little we heard of Papua New Guinean experiences through the narratives we received growing up. This was despite the best efforts of historians like Henk Nelson, Bill Gammage, Anne Dickson-Waiko, John Waiko, and later Noah Riseman to alert us to the colonial context of the conflict, and our responses to it.

One way in which I contributed to the war memory project was through extensive archival research to coincide, corroborate and cohere with the oral histories recorded along and around the Kokoda Track, and then further afield. The stories of women, both in their own words and through the eyes of others, stood out to me. This article is the first in a series that I will write and publish online which I hope will start discussions about how we might better write inclusive histories of the Pacific War, and extend our lens in Australia to consider the roles and responsibilities played as a colonial power.

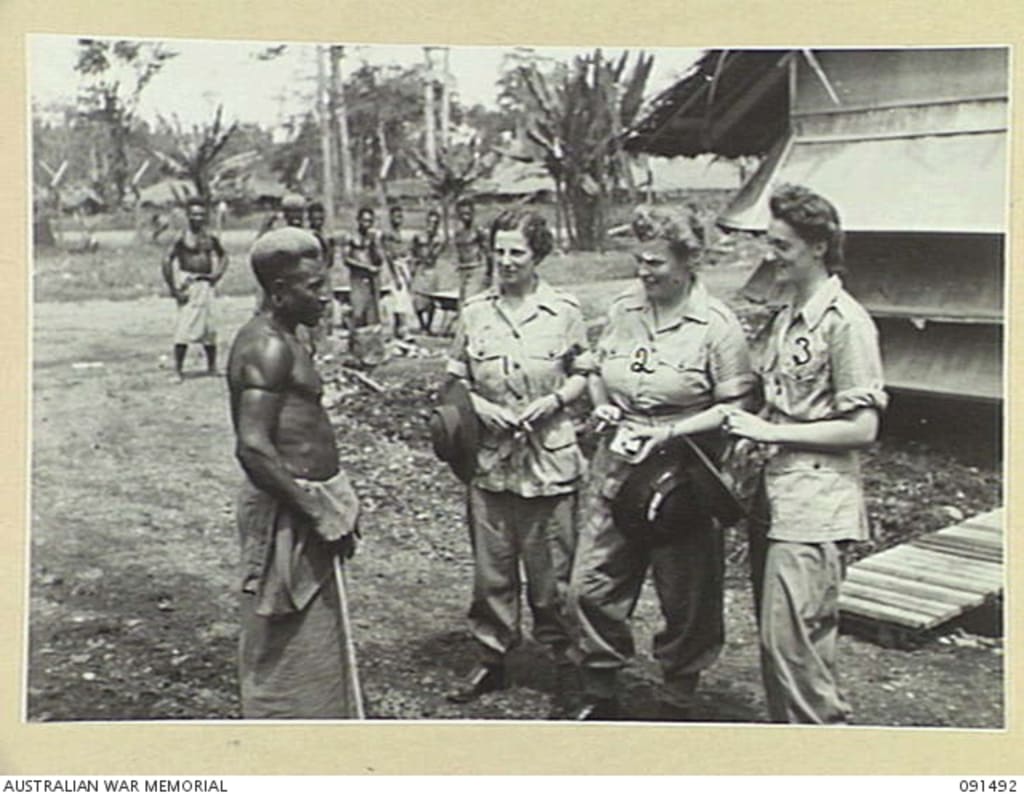

World War Two in Papua New Guinea is often remembered through the eyes of Australian troops, war journalists, and government officials such as the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU). These are male dominated, male-led narratives. They capture the details of the conflict in detail and depth. But the women who were impacted, who lived on and around the Kokoda Track, have been hidden in a haze behind the whizzing bullets, buried by the bombs and bodies. Kokoda, the place, has become somewhat static and history-less, and in the process, women have been erased from the landscape, despite their labouring on the land, birthing and raising babies, and plotting schemes for survival in villages and the bush around. Occasionally we get a glimpse of servicewomen or nurses, but these are few and far between.

To start the discussion, I want to go back to the pre-war period, when many Australians who went north to Papua or New Guinea were setting up plantations, and trekking the slopes of the interior in the hopes of striking gold. Those who ventured inland on the Kokoda Track were on a track that was well worn by locals beforehand - it was not a European construction. Many travelled along the Track to search for gold in the Goldie and Loloki Rivers. Mining contributed to the dedicated government station being built at Kokoda too - Governor Monckton decided to set it up in response to tensions at Yodda Valley Gold Mine. The Papangi and Bogi stations were closed in 1904, and merged to form Kokoda station. Local carriers made the move possible, as the station relied on carriers to bring goods from Port Moresby.

Women arrived alongside the male fortune-hunters and hopeful farmers, as wives, daughters, and then there were nurses and missionaries amongst other ambitious women who arrived in the Territories. The land for Saga plantation, on a 1000 acre plot, was leased by Jessie 'Pat' Searle in 1939—the wife of Clen Searle. The land was beside the Kokoda airstrip - an ideal location to receive goods being delivered by air.

The plantation was typical in that it was overseen by a manager, and Papuan labourers undertook the daily heavy labour. The Searles arrived in 1940, and were met by Jack McKenna at the airport. The Kokoda rubber plantation was nearby, run by Bill Graham and his wife Freda. The Kokoda plantation was on a plateau, a 'flattened spur of land, jutting from the mountain side and ending in a rounded point, standing well above the valley.' Pat wrote: 'one seemed to float in the air above a green carpet, as the steep clay cliffs were unseen from that position. Clumps of tall, old and beautifully shoaled majestic trees were growing precariously near the edges, with wild Begonias around their bases.' (P Searle, p. 133).

Saga was a little further away, and not nearly as well established. Pat recounted that even as they exited the plane, Papuans were applying to Clen for work on the plantation. Clen employed them on the spot, and the new recruits carried the family's cargo across the track to the top end of the airstrip, and then along a wider path to Yodda eight miles away.[1] After the walk, they came to the plantation and their home, which at that stage was a timber building with iron roof, the door secured with a padlock sitting quite clear of any trees as the land had been cleared by the first worker at Saga (P Searle, p. 131).

Every day on Saga began with '"fall in" for the labour'. Clen accompanied the employees to the field where they would be told the work programme for the day. Clen had an intermediary, Karengia, who Pat referred to as the "Boss boy." Karnegia came from Daru, but was 'a good Boss Boy with the local natives, thus a good help to us.'[1] Being a rubber plantation, the main objective was to successfully nurture the trees to maturity, and so land was cleared, and while this happened a nursery was established for the seedlings. As soon as there was enough land cleared and the seedlings were ready, they were planted with stakes for support. Land was constantly being cleared, with the tall trees too large to chop, once they had dried out, being set alight. Pat wrote: 'The men would sing and whopp as they slashed with long bush knives at the jungle growth, and finding a snake or a small animal was always greeted with joyful shouts as they chased it for their cooking pot' (P Searle, p. 132).

Food was crucial to the running of the station, with that being only one of the provisions the Searles had to provide - clothing and shelter also had to be maintained for their employees. Meat and hard biscuits were flown in each Friday from Port Moresby. They ordered frozen fresh meat for a while which Pat had to cut and portion out for the workers, but they soon reverted to tins again. She noted that some of the workers were married and took their rations back to their families at Awala and other surrounding villages. One of the reasons they reverted back to tinned meat was that tins were easier to carry around, to barter or exchange. Fresh meat did not last as long, and despite it being cheaper, it did not really work for the lifestyle and economies around Kokoda station (P Searle, p 132).

With the bombing of Pearl Harbour, many white women were evacuated from the Territories of Papua and New Guinea. The only women who did not leave the northern parts of the Territory seem to have been mission workers, particularly Anglican missionaries at Buna and Sangara mission station (Wetherell, p. 65). As a result, when in the archives I found I was having to read against the grain of patrol reports and accounts from white men who had remained to get glimpses of the experiences of women in the months leading up to the Japanese invasion and the destruction that resulted.

One source that afforded some critical insights were the papers of Gerald F X Brown. He was one of the patrol officers who undertook surveillance through his patrols, monitoring living conditions, making arrests, gathering recruits and taking census data. In his notes, he recorded that court sessions continued at Kokoda, a gaol continued to function, and government employees left from Kokoda to complete patrols. Europeans and New Guineans alike completed the government's administrative work: The task of enlisting men for work was one of his main focus areas. Over 1000 Orokaiva men were sent to the capital in 1942, Hank Nelson estimated (p. 81). Brown's recruitment strategies during his patrol in March 1942 helped contribute to that number. He described the Kokoda station - Bill Graham was the rubber plantation manager there, who lived in a 'barn of a place - much too big to ever be made comfortable.' (Brown, 24 March 1942, PMB 1162/reel 1, p. 11). He went on to describe Kokoda: 'Kokoda is really a very beautiful spot set amidst the lovely setting of the mountains… The whole station is a mass of lawns and flower beds' (Brown, 24 March 1942, PMB 1162/reel 1, p. 11).

The idyllic surrounds were a buzz of militarised activities already by March. Brown was woken next morning at 6am by the sound of a sergeant drilling his police. The following day those police received orders to accompany Brown and recruit 200 carriers that could go halfway to Port Moresby to collect stores. Before they left, however, there was some air activity — a Japanese plane machine gunned Kokoda station and dropped four bombs - all poorly deployed so they did not come close to the station or its inhabitants. Brown had been in the radio building so let Port Moresby know what had happened straight away. They had been concerned that the plane would try and land on the Kokoda airstrip, and even though it did not, the men decided it was best to keep rifles within 500 yards 'just in case.' Despite the relative lack of damage done through the attack, and the only real injuries being those suffered through the scramble to find cover, Bert Kienzle arrived at lunchtime to ascertain whether there was truth in the rumour that he had heard that they had all been annihilated. As Brown said, 'rumour travels fast in this country,' and it certainly did along the Track (Brown).

The Papuan and New Guinean station police were a significant part of the Kokoda community. Brown noted that they were recruited into the army the day after the raid, which 'speaks highly for their loyalty and courage.' There had been a parade the next day too, and none of the police, prisoners or rubber tappers had made a 'run for it'. Brown mentioned Cecil, a clerk with both European and Papuan or New Guinean parents who worked at the station, who was only 16. He 'never budged an inch and in fact had to be told to take cover; a courageous little blighter' (Brown).

Brown's writings offered further insight into the daily activities at Kokoda - the Europeans instructed the labour lines what to do each morning at 7 AM, and then the day continued on from there. A large part of the work that Brown did related to the management of Papuan and New Guinean labourers. He almost, on top of enlisting the aid of carriers, escorted 32 Papuan Infantry Battalion deserters back towards Port Moresby, but this task ended up going to Colin Davidson. Brown thought little of the deserters, in favour of more severe forms of punishment so that others who considered deserting would be deterred. 'These PIB are a rotten lot,' he wrote, 'and need very strict discipline.' Brown's anxieties escalated over the following weeks as rumours circulated about the potential for impending Japanese attacks. There was a growing imperative to round up an Indigenous work force that could help defend against the Japanese Imperial Forces. Despite the sense of foreboding, plantation work continued, with 55 bales of rubber carried to Buna on 2 April.

Orokaivans—the traditional land owners of the area—were increasingly under pressure. One man who deserted his work had heard that the village constable was looking for him so that he could be returned to his worksite, and committed suicide. Brown was in charge of making the investigation into his death, and was accompanied by a team of skilled Papuans: a medical orderly, interpreter, cook, 3 police and 12 carriers. The carriers were prisoners then being held at Kokoda, who were being put to task.

Together they walked through the villages of Kourondo and Sengi before arriving at Kausu. This was the young man's village. The haus cry was underway by the time Brown arrived, with women surrounding the house where the body lay. Brown recorded that the young man was only about 22 years of age, and looked perfectly healthy with no signs of violence on his body (Brown). Brown was confronted less by the suicide, and more by the women's responses to the death. The young man had not been married, but Brown wondered whether these women were his 'old flames' but he suggested that this was Orokaivan or Papuan 'custom' (kastom). The womens' faces and bodies were 'covered with mud and ashes and every so often one of these would get up and wailing, would run and dance round the village and throwing herself down would beat her face into the ground.' Brown recorded the findings from his inquiries and found that this Kauru man had been working at Sogeri. He 'had been caught' after deserting previously, and was being sent back to Port Moresby again when he ran back to the village. 'When he heard that I was after him,' wrote Brown, 'he ate a poison known as New Guinea Dynamite and died. He must have had a real fear of going back to Port to take such drastic measures to avoid it.' Another of the man's friends, Ewoki, had been in the same boat and also ingested the poison but not a fatal dose and he, although violently ill, survived. Brown found Ewoki and handcuffed him to Village Constable Hiwa, and sent him to Kokoda. 'I handcuffed him for his own protection for there is no doubt that he would again attempt suicide and probably next time with successful results.' Brown said he felt upset but the need for workers at Sogeri, which he considered to be a very safe location, for rubber production: 'a vital war necessity.' The rest of Brown's patrol revolved around finding men who had deserted their work in order to return to their families. There continued to be rumours and news of downed Japanese planes in the vicinity for example, and Brown's desperation to get his job done was evident. He found 78 deserters during the patrol by 11 April.

Once back at Kokoda, he was filling the gaols so that the prisoners could be more easily incorporated into work gangs. He reported on 3 June that 16 prisoners were in the Kokoda gaol, including two women: 'I am making a drive to get the roads cleaned up and am jugging anyone not doing their bit' (Brown). Reading between the lines of Brown's daily records, we can see the intense work that women were doing under the watch of colonial officials, to change the landscape, making it more accessible for commercial activities. In the end, some of their efforts would be utilised by the military forces.

What I hope is evident through this piece, is that there are many stories of women and their experiences of war that have been left unconsidered in our narratives of Papua New Guinea and the Kokoda campaign. Dr Victoria Stead has been doing some incredible work with colleagues at Popondetta. Margaret Embahe and Mavis Manuda Tongia, to draw further awareness and recognition. Blending her anthropological approach and my own historical methodologies, both archival and oral histories, we have discussed the potential to enrich our understandings and appreciation for the past and the ways in which the past lives with people today. And that is only the beginning of the ways in which collaborative work can enhance our understanding of Australia's historical ties to PNG.

Condensed bibliography:

Brown, Gerald F X, (patrol officer/native labour inspector) War diary, patrol reports and personal papers, PNG 1936–1965, PMB 1162/reel 1.

Nelson, Hank, 'Kokoda: And two national histories', Journal of Pacific History, vol. 42, 2007, pp. 73-88.

Searle, Jessie Lilian, Memini - I remember: Recollections of my life with Clendyn Edwy Searle in Australia and Papua New Guinea, 1995, see National Library Australia, MS 9425.

Stead, Victoria, 'PNG women’s wartime memories cast new light on Kokoda and the Pacific War', The Conversation, 3 November 2017, http://theconversation.com/png-womens-wartime-memories-cast-new-light-on-kokoda-and-the-pacific-war-85667

Wetherell, David, ed. The New Guinea Diaries of Philip Strong, 1936–1945, South Melbourne, Macmillan, 1981.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.