The Reconciliation

A small man goes for a small win against a giant state

Dzerzhinsky Square, Moscow

November, 1937

I squinted through the falling snow at the entrance of the looming prison opposite me. A massive boulevard separates us, and, anyway, the hulking Chekisti next to me will not let me go any closer. I cinched my overcoat tighter against the Moscow chill. One Party ration card does not provide enough for winter here. And my Bogdan is no longer a Party member. The fool has ruined everything with his tongue.

Why I am here, I do not fully understand, yet. But Comrade Stalin has ordered it, and so, I obey. One member of this marriage is still a dedicated Communist. I do not know what happened to Bogdan Alexeivich. I consider this an opportunity to find out.

Of course, the call in the early morning disturbed us all, as early morning calls disturb in this period of Special Measures. The Security Services have so many undiscovered enemies to see to, and it’s best to scoop them up when they are in their pajamas and groggy, so I’ve been told. Makes sense to me.

Of course, one cannot help wondering if a mistake has been made. There are so many people in this country; it’s inconceivable that mistakes haven’t been made. But the Chekist at our door is polite and accommodating.

“Sorry to trouble you, Comrade Grushova. The Party wishes your assistance in the delicate matter of your husband, Bogdan Alexeivich.”

What can I do but offer to help? He has been denounced as an enemy of the people, I know. But, as I said before, I understand that, even in our Soviet system, mistakes are possible. Comrade Stalin even says this. So, I must seize the chance to find out more, to ask him: What the hell were you thinking, Bogda?

My husband and I have been dedicated Communists for 20 years. We risked our lives in Ukraine, on the Volga, in Bulgaria and Germany, and in Ukraine again, all for the Revolution. I need to know: WHY?

Little Anna will be fine with Baba. I must go with this handsome Chekist.

Now, he is gone, no doubt, to more thrilling tasks than chaperoning a middle-aged, frumpy, old Bolshevik. His sullen companions, however, remain.

“There he is.” One of them mutters. I look, and, indeed, there is Bogda. His battered old leather case in one hand. He walks slowly, fragile. I think of the rumors I have heard of the NKVD’s methods, and I push them away. Anti-Soviet slander.

But, as he gets closer, trudging through the slush, I notice: The once tall and proud athlete is bent, perhaps not broken, but bent all the same. I feel a rush, a strange mix of gratitude and terror. Enough to stop lying to myself.

They have loaned him back to me to try and save his life. If he goes back in, he will not come back out again.

He stands on the curb, looking back and forth. He is unshaven, his blue eyes watery but sharp. The mop of black hair falls over his forehead. He looks like a mink sniffing at a trap, wondering whether to enter.

I embrace him anyway until his bag spills onto the street and he curses under his breath.

I don’t care. He is alive. For how long, I don’t know, but my Bogda is alive.

*

We have been separated many times, but this time was the worst.

I should say, "Is the worst." For even Masha, in her lock-step, Party brain, must know this reprieve is temporary. When the Georgian picks you out, he squeezes you dry. He may let you sit on the shelf, or throw you in the trash straight away.

But in the end, the straw-lined room in the basement awaits. Even she, she of glorious and eternal optimism for the Communist future, must realize this. How many true believers like us have trod this path already? Does she understand that her time is coming, too?

I will myself to enjoy the little pleasures. I embrace her back. The embrace becomes a passionate kiss until we are pulled apart by the Chekisti.

“Let’s not waste time. Get in.” The fat one unceremoniously tosses my bag in the boot, while the taller one gets in the driver’s seat. How much must one steal to be fat in the Soviet Union, I wonder idly. I smile to myself when the thought occurs: His time is coming too. The Yezhovschina will eat its own. I saw it in the faces of my interrogators.

I was deprived of sleep, kept in a tiny, stinking cell, pulled out for "questioning" every time I started to snore, which I am sure my cellmates appreciated. But I don’t think I looked as bad as those NKVD officers; no, I don’t.

Unshaven, too, eyes bloodshot, black circles under them… asking the same questions over and over, hitting weakly, out of frustration. Like every other good Soviet shock worker, a victim of quotas and production goals. I am sure they have them, too. So many arrests, so many confessions, so many shot. Facts? Who cares? Give us numbers.

“Bogda? Bogdan Alexeivich?” I realize I have been dwelling on captivity when I should be celebrating freedom. Outside the window, the bleak streets of Moscow pass by quickly, drab people moving fast, not stopping to talk, like a cinema film.

In 1937, one chooses carefully whom to talk to. It is usually better to keep walking.

“Yes, Masha dearest.” I hold her to me. “Sorry, just a little tired.”

“They fed you well, though? Hot water?” I stifle the urge to laugh as the fat Chekist glares at me in the rearview. Masha lives in a dream world. Oh, there was hot water alright. Scalding hot, if you played your cards right.

“Lovely, Masha, lovely.” I squeeze her hand to signal silence. She nods imperceptibly. We have been Party activists for almost as long as we have been married. Masha is stunned in the glare of Stalin, but she is no fool.

“Of course. We’re staying in a lovely hotel, dear. Nothing but the finest for the assistant director of the Institute!”

I look at her and read the lines and grey hair. Why couldn’t I just do what was demanded of me? How much would it cost me? Cost her? Cost Anna? “I do hope there’s champagne.” I look out the window and see we are passing the Kremlin. The vaulting red brick walls and towers, designed by a long-ago despot to intimidate his people. Now coming in very handy for another.

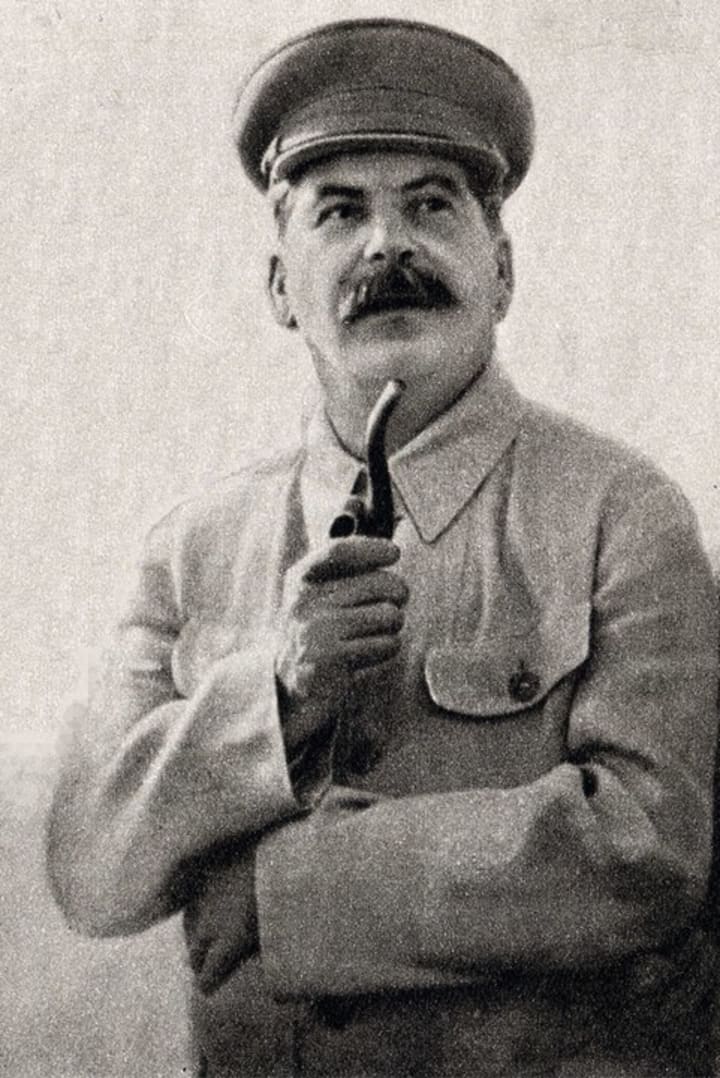

I imagine the Ossetian with the deformed arm and the pock-marked face, in his cavalry boots, smoking his long pipe, poring over the lists. My name is upon them. He comes to it, reads my name, and smiles.

The fat Chekist seems to read my mind. “Are you watching him? Because he’s watching you.”

Masha and I hold hands in silence until we reach the hotel.

*

Sovietskaya Hotel

Moscow

The fat Chekist, the rude one, had stayed behind in the car. The driver was blunt. “You can’t leave this room without permission. Room service brings your meals. Vodka and wine, too, if you run out. But you mustn’t leave without permission. Understood?”

Only now did I notice that the obligatory “Comrade” of public discourse was gone. I looked at Bogda, his eyes downcast, like a convict. “That will be fine, Comrade. Thank you.”

“Hmm.” He walked back to the elevator, without a word. I closed the door to find Bogda, holding his hat like a job-seeker, looking around the room. I imagined it must be a change from the cells of the Lubyanka.

There was a gigantic bed, lumpy from the looks of it, and a beautiful radio. Outside the window, Moscow hummed with new cranes and derricks over every piece of available ground.

“Building Socialism,” Bogda muttered.

“Yes, of course.” I sat on the bed. He followed suit. I noticed the rings around his eyes again. “Have a shower, my love.”

“Yes. A shower.” He rose mechanically and made his way to the bathroom, shedding clothes as he did so. I scolded him as in the old days.

“Bogda, so messy. Must I always…”

He glared at me, frightfully. I took his clothes and put them over the chair. I sat on the edge of the bed, watching the New Moscow generate itself. Perhaps this, all this, was part of the price.

Bogda was taking forever. I peered in to check on him and saw him standing there, staring at me frankly. “Get in.” He said.

I had not made love to this man in six months. We were strangers, long before the Black Marias came for him. But, I did not know when I would ever see him again.

So, I got in. And I did not regret it.

After, so long after, I held him, arms around his waist, feeling his ribs as I had not since the Civil War. He lay on his side, smoking, staring out at the Moscow skyline, deep in thought. I say nothing.

I know my husband. He needs this time to digest new events, new twists in the plot. This, more than anything else, is what has doomed him. He lacks the mental elasticity of the New Soviet Man, the ability to switch gears effortlessly, between peace and war, love and hate, truth and lie. For Bogda, a judicial case must be made for every change in direction.

We do not live in this world anymore. We have not, not since Trotsky left, and Bukharin was silenced.

Bogdan thinks I am enraptured by Stalin, but that is not so. I merely accept him as inevitable, a greater good in an ugly time, when the rest of the world is arming for war. Surely, we need our factories and ugly men in tall boots, too?

Suddenly, Bogda sits up. He walks over to the radio. It is only then that I see the welts and horrible bruises on his back. He switches it on, leaving Tchaikovsky to play, and comes back to me. He points under the covers and bids me follow him.

*

As every Soviet schoolchild knows, the Soviet Union is by far the largest country on earth. Eleven time zones, and something like 17,000,000 square kilometers.

Vast, beyond imagining. So vast, that, if you ship someone far enough east, you need no longer build prisons with walls. How typical of us, that, when granted with a miracle like this land, we use it to perfect the prison.

How ironic, too, that, in this vast land, the only free space left to Masha and I is a pocket of a few square centimeters under two pillows. Only here, can we live freely, and only for a little while. However fleeting, it exists, an Autonomous Region with its own rules.

I shall call it, the “Grushov Autonomous Region.” That’s a good name.

I kiss my wife tenderly. She giggles, in a way that takes me so far back, to times when famine and cold did not hurt so much, not if I could be with her. “Welcome to the Grushov Autonomous Region,” I whisper. “Here, and only here, can we speak the truth.”

“Did they beat you?” She whispers a look of guilt on her face. I wish it were for not being able to stop the thugs. I know it is, instead, for us having displeased Stalin.

“You saw the marks. Of course, they did. Every day, and night.”

She chews her lip. It reminds me of my conversation with Volokansky, my cellmate, about his wife. He described her so well. “Well, I hope you apologized to Comrade Stalin, and Comrade Yezhov, for all the extra work.” We all laughed at that one, even the Priest.

“The bastards.” She surprises me. The light in her eyes is fearsome, and I have seen this woman kill. “Bloody Yezhov, he’s in for it, once Comrade Stalin finds out.”

I shush her, disappointed. “Yezhov is a disposable tool, Masha. Once Stalin is done with him, he will burn. But another one will be found to take his place. The point of all of this is to consolidate the rule of one man. Nobody, nobody except for him, can feel safe.”

“You’re wrong. Comrade Stalin would never approve of these methods…”

“We carried out these exact same methods. Against the Whites. Against the Left and Right Deviationists. Against the Kulaks. And, against the old Bolsheviks. Perhaps, you mean, he would not approve these methods against us? Stalinists?”

We lay in silence for a while, emerging from the pillows to share a cigarette and a glass of vodka. I drink slowly. I need to stay sober. I have things to say.

I watch her face. I know where she is in her thoughts, for I am there too.

We are in Ukraine, wrecking grain mills, killing cows, confiscating pood after pood of grain. Watching the already starving kulaks try and comfort their scarecrow children, but all of them knowing it is the end. They are doomed, if lucky, to starve in each other’s arms. If unlucky, to live long enough to eat each other.

“Life has become more joyous!” Wasn’t that what Stalin said? We look at each other, and we realize we have been condemned, not by Stalin, but by ourselves.

Those starving kulaks. Now, they will have their justice.

*

I pull the covers and pillows up over my head. Now, Prokofiev plays. Surely, Shostakovich is next for the Lubyanka.

Bogda is lost, a vacant look on his face. I know where he is, and I was there too. Ukraine.

“You cannot dwell on it. You can’t make an omelet without breaking some eggs.”

“I am sick of this fucking saying.” He hisses. “Those people had no eggs. We made sure of that.”

I know I must change the subject. He has never been the same since Ukraine, and that has led him here. An increasingly loose tongue. A tendency to point out reality in contrast to propaganda. Fatal tendencies.

“Do you know why I am here, Bodgan Alexeivich?” I stroke his cheek, in contrast to my use of his patronymic. I see him soften. I know my husband.

“They sent you here. To convince me to testify again Vymel, Logotin, and the others. Isn’t that right?”

“Yes. Think of me. Think of Anna. Damn your ‘Revolutionary Principles,’ you old fool. By the time this is over, there won’t be anybody left who hasn’t soiled his britches.” I grab him and shake his shoulders, relenting only when I can tell he has been harmed there. “It’s about you, and me, and Anna. That’s all you’re responsible for. Those others you are protecting? They broke the wheels, killed the cows, emptied the soup pots, too. They shouted for Trotsky to die, for Kamenev, and Bukharin, and Kosior, and Ryutin to die… they all did, just like us. If we deserve it, so do they!”

He breaks down, sobbing, his mask of strength finally breaking. I know my husband.

But then, he surprises me. He grabs me and hisses.

“I cannot save myself by testifying. I cannot save you, either. We are both dead. The only person we can save is Anna. And that is only if I hold out as long as I can. And there is one more thing…”

“What?” I am crying now, too. How we once reviled emotions as a bourgeois relic. Now, they are all we have.

“You, Maria Petrovna. You must denounce me, in the strongest possible turns. This, and only this, will buy us the time we need.”

I look at him, trying to feign surprise, knowing I am a poor actress. Surely, they must have told him?

*

The sun is setting over Stalin’s Moscow. We have fallen silent again. A passable dinner has arrived, sturgeon and potatoes, certainly far better than anything I got inside. To my surprise, I can only eat half. My stomach has shrunk, used only to thin soup and kasha.

I sip at my vodka and light a Belomor. The sun dips behind the buildings, casting an eerie light on the room.

Freedom. It’s as close as I’ll ever come again in this country. To be honest, the freest I’ve ever felt was outside, in Germany, England, France. What does that say about our glorious experiment?

Masha comes up behind me. I set down my vodka and stub out my smoke, and we fall back into bed again. After, we return to our Autonomous Region. This will be difficult.

She holds me, tentatively. She often refers to herself as a “babushka,” and this makes me laugh. Years of struggle and sacrifice have made her lean, but she retains the same womanly features that drew me to her in the first place. The same dark eyes, alabaster skin, petite body holding the curves of a Swiss ski hill. I want to make love to her now, but I need to tell her something.

Also, I need to… dear God. Fatigue pulls on me like a drugged man. She rubs my neck, which makes it worse… she has no idea how they withhold sleep there. She has no idea…

*

I awaken first. Little fire tips of dawn infiltrate the room. I get up, light a Belomor, and stride over to the balcony. The fire rises under the thousand construction sites of Moscow, the University, the Metro, the Civic Pool, Lenin’s Library… as if Communism is lit from below by the blessing of ancient gods!

I suck in the terrible cigarette like a greedy, naked, devil… thrilled to see the city of my dreams awaken, a place for me, and those like me…

And then. And then, I look over at my husband, and I realize he is not invited. Even I, if one is to believe him, is not. Perhaps even Anna will never swim in this pool, nor read in this library. Why? Why has this revolution locked out its own children?

I sit next to him on the bed as he snores mightily, a sure sign he will never get up, at least, no time soon. I throw back the covers. It is my right, he is my husband.

Written on his body, is the sign of our struggle. Twenty years of sacrifice, danger, torture.

There are bullets. The bullets of Wrangel and his men. Of Pelitura.

There are beatings, the White Guards, and the Ukrainian Nationalists again, but also, the kulaks, fighting to protect their scarecrows. Those, he is not so proud of.

The most recent ones, these ones stop me cold. The indents of chains around wrists and ankles, handcuff marks, ratcheted too tight. The chains, again, disgustingly, applied to the scrotum.

The hundred little burns, of Belomors, like the one that dangles from my mouth, all over his body. These are recent, not the punishments of ancient history, but of a displeased god we have always served so loyally.

I stare at the burns on his balls, the ones around his ass. My cigarette falls from my mouth, as I watch, paralyzed, and somehow, he wakes up.

“Masha! Masha! You’ve started a fire! Put it out!”

In a panic, I throw a cup of liquid, realizing too late that it is vodka.

“Oh, Jesus, you silly girl!” Bogda beats at the flames, putting them out as he collapses in laughter. “You’ve burned off my undergrowth!”

I laugh now, reluctantly, then, greedily, savoring the moment as a little rebellion. “Open a window, damnit!”

Bogda grins. “You open it, you’re the one who set me on fire, you Mongol!”

*

The Autonomous Region is restored. We dwell beneath our pillows and sheets. Hunger gnaws at me, but I know what I must say.

She looks at me, hopefully. I will dash her hopes. I know everything. They told me everything.

“You betrayed me. You, my wife, for 19 years. You betrayed me.”

I watch her dissolve, in slow motion, until she becomes a cesspool of tears. She tries to speak but can make no human sound. I watch her with understanding, like a god watching mortals, because I have heard this from the others, and I know every story is the same.

Volokansky, the Party Boss: “My wife betrayed me.”

Father Evgeni, the Orthodox Priest: “As did mine.”

Colonel Kologin, the Air Force Ace: “So did mine.”

It is not that the women are weak. It is that they have children, children they must protect, above all else. This means that their choice is stark, really no choice at all. And it means that their husbands, if they are any sort of men at all, can never blame them.

I watch my wife dissolving in tears, and think of my little girl, eight years old, on Crimean holiday. So, happy. Not knowing the Soviet Union would never allow her to stay this way.

Some men die with Stalin’s name on their lips. I want to die with Anna’s, but I know I will not. Because such is the vengeance of Stalin, that he will crush her out of nothing but jealousy.

So, it is to be “Great Stalin, I die for you!” So, it must be, if it will keep her alive, keep her alive until she can say, clearly, and with conviction: “Fuck you, Josef Vissarionovich.”

Masha reaches out to me, and I take her. “Sssh. Calm. I know the situation.”

“How… how could you?”

“I know the situation because it is everyone’s situation. They play the same game with us all. All of us thousands and millions. Trade the husband, for the wife, for the child. If it were me, I would’ve done the same.”

She stares at me in orange light. “Me?”

“For Anna?”

She nods, like an unconvinced soldier. “For Anna.”

I hold her, but she is brittle. I am not surprised.

Comrade Stalin has his ways. He is as much in this bed as I am, as she is.

This no longer matters. All that remains is to convince of her of what she must do. And I know just the trick.

*

He has lain across from me, watching me dissolve, every bit as merciless as his torturers. He is a Bolshevik, after all.

I remember now, after years of suppressing it, something he said to me, as we watched a kulak village burn in 32.

“This is Bolshevism, Masha. Seeing what is to be done, and doing it. And someday, someone will see what is to be done to us, and they will do it, too.”

I had stared at him, open-mouthed then, shocked by the conversion of a true believer. But those starving little babies, lying there, open-mouthed…they had an effect on me, too.

“They are doing it to us now, aren’t they?” I whisper to him.

“What was it Lenin asked, back in 17?” Bogda asked, ever the Socratic teacher.

I thought for a moment, but the answer was never far away. “What is to be done?”

He turned to me and gripped my little hands in his big ones. “WE are to be done, Masha. We are. Listen to me, very carefully. Listen to me, and maybe…”

“Anna? The memo in the drawer?”

His eyes light up. “Yes.” Bogda kisses me with sudden fervor. “What a good conspirator.”

We laid there for a while longer, relishing the last moments of our Autonomous Region. Then, we emerged, saying nothing else to each other, but eating caviar, smoking cigarettes, drinking vodka... We steal last moments from the Land of the Soviets like a gang of raccoons. We make out like bandits, and we make…

Love, and one last phone call.

*

I feign sleep, while Masha pleads with the Chekisti outside for a call to our daughter.

“You can listen in.” She sweetens the pot. “I know this Deviationist’s game, now.”

I can picture her dramatic face, the failed actress face, and I almost laugh.

*

“Mama? Mama, where are you?”

I bite my lip. It is late, I know. We Soviets are used to late calls now, but they are never good news. But poor Anna is only 12.

She must grow up faster, if she wants to learn. “Is the Chekist still outside?”

“Oleg? Yes, mama.”

“Open mama’s clothing drawer, the second from the top.”

“Yes?” A sound of shuffling.

“Pry back the bottom, and you’ll find a false compartment.”

“Mama? Oh, no, mama!”

“Yes, honey, I know it is hard. But you must show Oleg this compartment. Your father has confessed to anti-Soviet activities. To me. This will provide State Security the necessary evidence.”

“Mama, please.” Anna sobs now, and I can hear a man’s deep voice. Oleg, no doubt. I realize that my husband, and probably I, have but days to live.

“Anna Bogdanova! What kind of Bolshevik did we raise you to be?”

“Honourable, ruthless, and truthful!”

“And did you not promise, that if Comrade Stalin was threatened, that you would denounce anyone? Even your father?”

“Yesss… Oh, Mama!” I can see them now, hand in hand, walking the Volga banks, across from the city named for his murderer, sharing the secrets of father and daughter. And I know, I will never see them again.

I hang up the phone. He looks back at me, from where he has been brooding, where the snow coats the embryo of the New Moscow neither one of us will live to see.

My husband smiles at me, as the heavy boots sound in the hallway. As we prepare for one last mission for the Motherland.

*

July 26, 1932

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Ukrainian SSR

Dear Comrade Bukharin:

I write to you as an old comrade, with a heavy heart. We have seen much together, you and I, Nikolai Ivanovich, and amongst the worst of those things was famine, was it not?

Perhaps, we may both consider the famine of the Civil War times a necessary evil. Many of those who starved were our outright enemies, after all. Of those who were not, often, we simply couldn’t feed them and the Red Army too.

But this, this is different. I don’t have to share my horror stories with you. You were the editor of Pravda once; you have your sources still, I am sure.

We, and by "we" I mean, HIM, are murdering these people only to elevate HIM to the godlike status he so desires. In so doing, we are destroying the desire of the people to work; we are killing the most productive farmers, and hanging a sign around their neck which reads, “Kulak.”

We are murdering the Ukrainians, almost as an afterthought. I pass through villages, villages where every single person is dead or dying. I am sure, once they are cleaned up a bit, they’ll make nice places for Russians, Georgians, and Jews.

I write this not to lecture you on something you once warned me about, but perhaps only to lecture myself. It took me so long to admit it, after years of being stubborn, that we have become the menace we always feared.

We steal from the people. We brutalize them, without trial. We elevate the idiot, and crush the questioning man. We steal from the future, to feed the present.

Well, Comrade. There is nothing here to feed anyone anymore. Except for the “People’s” representatives. I have my soup and bread, as always. I could have vodka and caviar, if I wished it.

But I cannot eat, not without seeing those walking skeletons.

I apologize, Nikolai Ivanovich, for not standing by your side on collectivisation. Your words have proven prophetic, and now I stand as a coward, too weak even to shake his wife from her craven devotion to HIM.

All is lost, all is lost. You are doomed, and so am I. Every bit as much as those scarecrows drifting past my window.

If I see you on the street in Moscow, I wonder? Will we greet each other? Will we grant each other life? Or will we drift past like ghosts, like the ghosts we already know we are?

Take care. Run, if you can.

Bogdan Alexeivich

The senior NKVD officer searching the Grushov apartment on the Embankment raised an eyebrow as he finished reading. His deputy watched him expectantly. “What do you think, Comrade Colonel?”

“Hmm. It’s good. Will make a nice addition to what we’ve already got on Bukharin. Make it ‘Exhibit ‘A’ on Grushov. This is the kind of thing that got Yagoda shot. Who told you where to find it? That’s a good spot, even for these crafty old Trotskyites.”

“Grushova. She told the kid.”

“Trying to sell out the old man, hey? Well, it won’t work. If she knew where it was, how come she never handed it in? No, fuck her. Process her under Article 58 for now.”

“Yes, sir. The girl?”

The Colonel sighed. It was always messy when it came to the kids. He imagined what it would be like when they came for his kids. Because he knew they would. “Orphanage. She’s a simple one. Just make sure Beria doesn’t get her.”

Around the corner, Anna Bogdanova Grushova began to cry softly as she realized her mother would never return. And the woman NKVD Captain watching her pencilled a note in her book on the Colonel’s comment about First Secretary Beria.

Another life ending, another in limbo, and one more being readied for the slaughter.

Life has become more joyous. The quota is met.

About the Creator

Grant Patterson

Grant is a retired law enforcement officer and native of Vancouver, BC. He has also lived in Brazil. He has written fifteen books.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.