A Seventh Man: The Art of Activism

How do we get humans to treat other humans like humans?

‘Why does the Western world look to migrant laborers to perform the most menial tasks? What compels people to leave their homes and accept this humiliating situation? In A Seventh Man, John Berger and Jean Mohr come to grips with what it is to be a migrant worker – the material circumstances and the inner experience – and, in doing so, reveal how the migrant is not so much on the margins of modern life, but absolutely central to it. First published in 1975, this finely wrought exploration remains as urgent as ever, presenting a mode of living that pervades the countries of the West and yet is excluded from much of its culture.’ (Berger and Mohr, Verso: 2010)

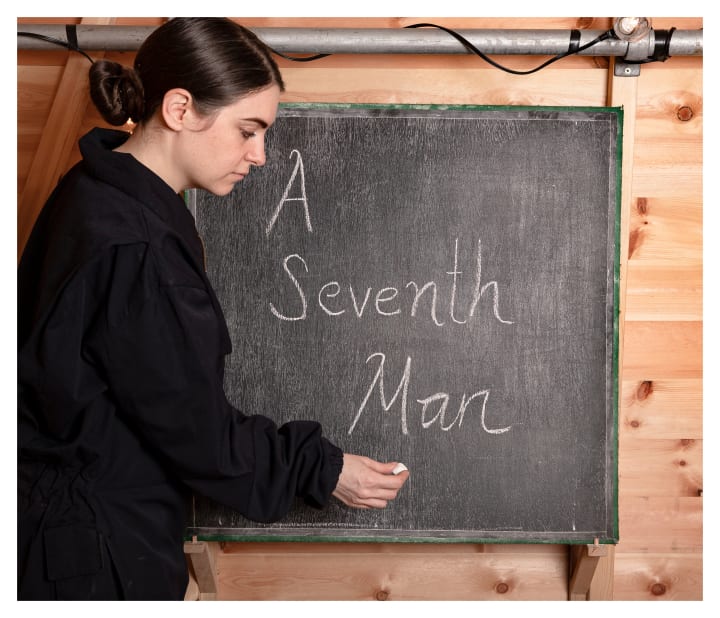

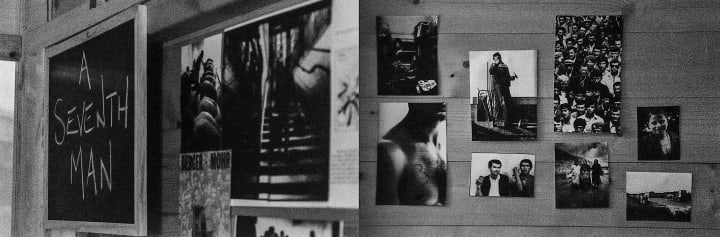

Ten years after the republication of the book A Seventh Man, the world still fraught with these same sorry issues, I had the opportunity to work with Pinchbeck & Smith to create a theatre show of the same name. This immersive production was based heavily off of the book, bringing it to life if you will. And, though the book itself focuses on just European migrants, the show works to draw parallels with issues many migrants all over the world face today; highlighting the widespread levels of exploitation they are still subject to.

Before the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 swiftly shut us down, we had already toured around the East Midlands with plans of applying to further theatre festivals across the UK and beyond. The process of creating this show was a very personal one to me, my father being of North African descent and following almost the same journey that the people featured in the book, A Seventh Man, took all of those years ago.

As a family, we would make the journey back to my father’s home country three days before my tenth birthday. Six years later, on the 4th January 2011, the first of many protests would break out, the country saying no more to the dictatorship regime they had suffered under for decades. This move would turn out to be the start of the Arab Spring (something I've since explored in my own work).

I was very lucky to be of dual nationality, making me able to return to the UK once it became clear that (even though the worst parts of the revolution seemed to be over), normal life was likely to be disrupted for the foreseeable future. Many people suffering through the horrific and violent conflicts playing out in front of us today (Syria and Yemen come to mind) are not as fortunate. Even when they are able to emigrate, they are often treated like second class citizens, scapegoated by some of our most powerful institutions, or are subject to hate crimes – as we have seen recently, with the rise in targeted attacks against Asian communities.

Our team consisted of myself (performer/co-divisor), Michael Pinchbeck (producer/director), Ollie Smith (producer/director), Matthew Cooper (sound designer), Ryan Chadwick (musician), Adam York Gregory (videographer), Olwen Davies (performer/co-devisor), Emily Bickerdike (performer/co-divisor), Hayley Doherty (understudy/co-divisor), Emily Cook (dramaturg), and Natalia Piotrowska (dramaturg). Julian Hughes also worked with us to take some fantastic promotional shots, whilst Dr Rhiannon Jones and Simon Burrows provided us with a wonderful moving venue… The Social Higher Education Depot, or, S.H.E.D!

The process itself was a collaborative one, with each of us spending the first session deliberating about the book, current events in the world, and experiences written within the pages that related to us personally. We discussed Berger and Mohr’s use of language, how imperative the imagery was to the work, the rises, falls, and crescendos, and the rawness of the parts of the book which were written in a second-person perspective. The writers focusing on the actions of one person, of their departure, work, and return, reminded us that this person could be any one of us.

When I read the book, the experiences that these people had pre-1975 reminded me of those currently fleeing a place of terror. It reminded me of the refugee camps of Calais, the strive for a better life, the scandal of Western companies knowingly hiring immigrants without citizenship in order to exploit them, the loss and gain of family, an unattainable dream – a universal human experience – the drive to make it happen and the cold moment of disillusion when you realise that perhaps, the dream is just that.

Much like my father has spoken about when he first moved to the UK around the 1980s, and still says now… the migrant doesn't always see this strange land as a forever place, but more as a kind of dream; or an adventure that has gone on too long. They see it as a place of transit, a place that they will eventually escape.

You long to hear your own language spoken. You long to eat your own food, hear your own music, you long to have the same opportunities in your hometown as there are in this foreign land. You spend your days dreaming of returning to your family – or taking your new family home with you. You ignore your life wasting away around you, you imagine that nothing has changed at home even though this new land has changed you. You cling to any semblance of home and you are villainised for it. You know it is only a matter of time before you get out. Your mind is a liminal space. You are in a liminal state of mind.

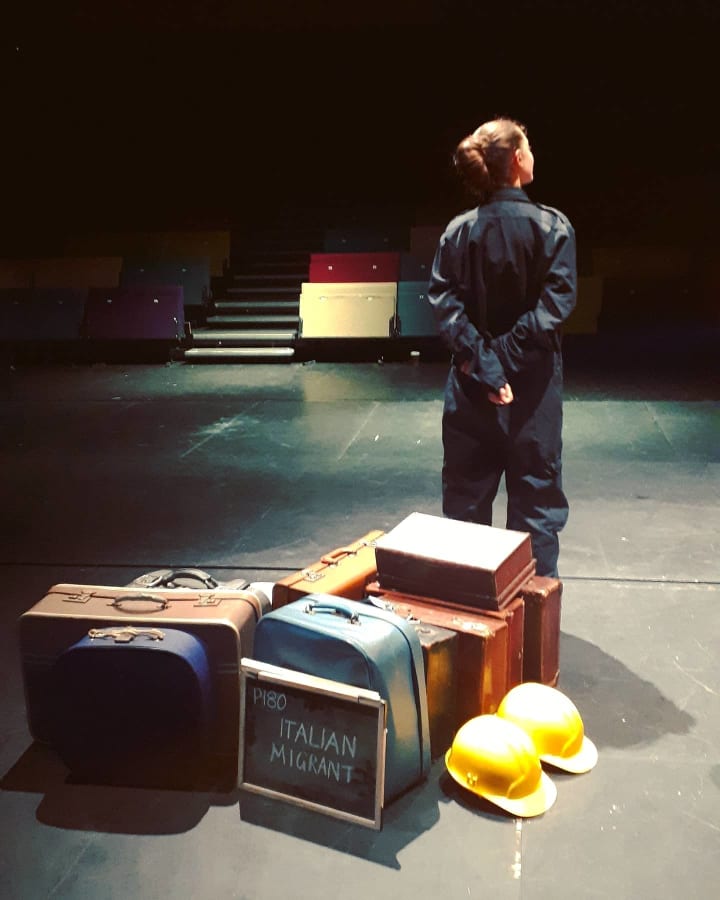

The above discussions stimulated a lot of rich imagery which we did our utmost to include in the show through the forms of costume, ever-changing environments, physical routines jumping directly out of the book and living through the performers, slideshows, and 3D miniature recreations of the cities or workspaces described. During the process of creation, we used verbatim quotes from the book, experiences of present-day migrants, and stories from my own father. We also went to great lengths to immerse our audience within the environments we had created – a staple tool in the Pinchbeck & Smith handbook – aiming to bridge the present gap which sees a lot of us in the Western world emotionally distance ourselves from 2nd and 3rd world issues (often created by us in the first place).

Seven audience members are invited to become migrant workers on this journey. They are met outside by the performers who give them a suitcase before bringing them into the S.H.E.D, which variously becomes a truck, a train, accommodation barracks, a border control post and an overbearing factory. This immersive performance, like the book, concerns a dream/nightmare. The existence of the migrant worker. (Pinchbeck & Smith, 2020: Online)

Using a fantastically versatile venue like S.H.E.D to put on this show, greatly helped with our mission to make audience members a part of the piece instead of encouraging them to remain passive behind an invisible forth wall. The claustrophobic elements of the environment, alongside the emotional context of the writing, worked to create a space which audience members fed back as ‘intimate’ and ‘perfect for the piece’. We also got quite a few people telling us how much the show made them realise what they don’t know but would like to learn!

Making audience members curious enough to pursue further knowledge on the subject is something which was at the forefront of my mind during the process of this show’s creation, and is a consistent aim during the creation of my own work.

From the perspective of a recent BA graduate of Contemporary Theatre and Performance at MMU (now, Drama and Contemporary Performance at Manchester School of Theatre), working on A Seventh Man with Pinchbeck & Smith was an invaluable experience; the topic explored, being one very familiar to those looked at within my own research. It not only gave me firsthand knowledge of the practical measures that need to be taken to get a production off the ground, but also allowed me to get a real in depth look at how theatre works as an industry; even if theatre as we know it has inherently changed over the course of this pandemic. Alongside being able to collaborate with artists that offer a range of diverse perspectives, my time with this production has helped me to develop my own practice and make better decisions as far as my work is concerned.

The questions I would ask are… Has anything changed? What can we do, past the point of this show, to change public perceptions of migrants? How do we reach people who simply don’t want to hear about it? Although Covid ironically put a border around our show about borders, I would argue that this pandemic has, if anything, made the questions asked in A Seventh Man even more relevant.

Has Covid had an effect on people’s viewpoints about migration? Has the experience brought us closer as a planet, or divided us further? Made us rejoice at the idea of immersing ourselves in an array of different cultures, or solidified our views that borders are there for a reason? Could this virus be temporarily hiding a multitude of rising discriminative views?

How do we get humans to treat other humans like humans?

About the Creator

Outrageous Optimism

Writing on a variety of subjects that are positive, progressive and pass the time.

We're here for a good time AND a long time!

Official Twitter: @OptimismWrites

Author Twitter: @gabriellebenna

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.