Why We Read Books

The Psychology Behind Our Literary Choices

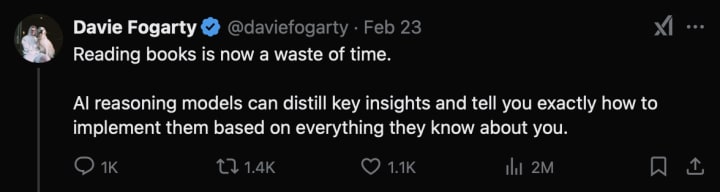

Here is some context as to why I am writing about reading. It is based on something I saw on social media:

Whilst perusing social media, I saw a post on Twitter (X) which discussed the point of reading. Whether ironically or unironically, the user had asked what the importance of reading books was and how it was probably a waste of time since AI could summarise the key points of a particular book after having machine-learnt about the reader themselves. This therefore meant it could give key insights into the book that would help that reader in particular to gain the knowledge that would be worthy to them from the book. Honestly, I have never seen something that has missed the point of reading so much in my entire life. I continued to make a snide comment about the user's lack of proficiency for reading, meaning it should not concern them. But let's take a look at why people read in the first place to attempt to tackle this issue.

Don't believe me? Check out the post...

Ready?

Why We Read Books

For centuries, reading has been an integral part of human culture, shaping societies and individuals alike. Whether we read for knowledge, entertainment, or emotional connection, books have remained one of the most enduring and transformative aspects of human experience. Despite the universal nature of reading, the reasons people engage with books differ greatly, influenced by psychology, personal needs, and even societal expectations. Some readers seek intellectual stimulation, while others turn to literature for comfort, escapism, or self-discovery.

The motivations behind reading are diverse, spanning from entertainment to intellectual curiosity. Some read fiction as a means of emotional engagement, immersing themselves in narratives that evoke empathy and allow them to see the world through different perspectives (Mar et al., 2006). Others turn to nonfiction as a means of personal or professional growth, acquiring knowledge that enhances their understanding of the world (Schwartz, 2018). Additionally, cognitive psychology suggests that reading can stimulate neural pathways associated with empathy, problem-solving, and creativity, making it a valuable cognitive exercise (Zunshine, 2006).

Furthermore, the genres people choose to engage with often reflect deeper psychological needs. Thrillers and horror novels, for example, can provide a controlled way of experiencing fear, allowing readers to process emotions in a safe environment (Clasen, 2017). Romance novels, on the other hand, offer emotional reassurance and idealised narratives of love and connection (Regis, 2013). Meanwhile, historical and scientific nonfiction caters to those who seek an objective understanding of the past and present, reinforcing a sense of knowledge and control over an uncertain world (Carr, 2010).

This article will explore the psychological motivations behind reading, examining why individuals gravitate towards certain genres and how the experience of reading fiction differs from that of nonfiction. Ultimately, by understanding why we read, we can gain insight into the profound role literature plays in shaping our minds, emotions, and worldviews.

The Fundamental Reasons We Read

Escape and Entertainment

One of the most common reasons people turn to books is for escapism and entertainment. In an increasingly fast-paced and demanding world, reading offers a mental refuge—a way to step outside reality and immerse oneself in another world. Psychological research has long suggested that engagement with fictional narratives allows readers to temporarily disengage from their own concerns, reducing stress and promoting relaxation (Green et al., 2004). This is particularly evident in genres such as fantasy and science fiction, where readers can explore alternative realities free from the limitations of everyday life.

Beyond simple distraction, escapist reading also has emotional and cognitive benefits. Studies show that immersive storytelling can trigger the brain’s reward system, releasing dopamine and producing feelings of pleasure and satisfaction (Nell, 1988). This explains why people often turn to books as a form of self-soothing, much like watching films or listening to music. Escapist literature, however, is not merely about avoidance—it can also provide catharsis. Horror, for example, allows readers to confront fear in a controlled environment, processing emotions in a safe and structured way (Clasen, 2017). Similarly, romance novels offer emotional comfort, reinforcing ideas of love, security, and fulfilment (Regis, 2013).

Knowledge and Self-Improvement

While some read for escape, others engage with books to gain knowledge and improve themselves. Nonfiction books, in particular, serve as tools for education, personal growth, and acquiring expertise. This is evident in the popularity of self-help books, biographies, and historical accounts, all of which allow readers to learn from others' experiences and insights. According to Carr (2010), deep reading enhances critical thinking and cognitive abilities by requiring sustained attention and engagement with complex ideas. In contrast to the rapid consumption of online content, books provide a more reflective and immersive learning experience.

Educational theorists argue that reading nonfiction fosters intellectual curiosity and lifelong learning (Schwartz, 2018). Many people read to stay informed about world events, develop new skills, or understand complex issues. Scientific and historical works, for instance, provide context for contemporary debates, allowing readers to engage with current affairs in an informed manner. Additionally, psychology books can offer insights into human behaviour, helping individuals navigate relationships, career challenges, and personal struggles. This desire for knowledge-driven reading reflects the human tendency towards self-improvement, with books acting as guides for those seeking both practical and philosophical understanding of the world.

Social and Emotional Connection

Fiction, in particular, plays a vital role in fostering social and emotional connections. When readers engage with well-developed characters and intricate narratives, they experience emotions vicariously, building empathy and a deeper understanding of human nature. Research suggests that reading literary fiction enhances the ability to interpret emotions and social cues, a phenomenon known as ‘Theory of Mind’ (Zunshine, 2006). By putting themselves in the shoes of fictional characters, readers practise perspective-taking, improving their ability to relate to others in real life (Mar et al., 2006).

Furthermore, fiction allows readers to process their own emotions by engaging with narratives that reflect their personal experiences. This is particularly evident in coming-of-age novels, where readers find comfort in seeing characters struggle with similar identity issues, insecurities, and life transitions. Literature can validate emotions, offering reassurance that others have faced similar challenges and overcome them. Additionally, books provide a means of communication between readers, fostering discussions about shared experiences and perspectives. This is why literature is often at the heart of book clubs, classrooms, and social movements; it creates a shared space for dialogue and understanding.

Identity and Belonging

Books also play a fundamental role in shaping identity and fostering a sense of belonging. Many readers turn to literature to explore aspects of themselves that they may not otherwise have the opportunity to confront. This is particularly true for marginalised groups, who often find representation and affirmation in books that reflect their cultural, gender, or personal identities. Reading about characters with similar experiences can be empowering, offering a sense of validation and community (hooks, 1994).

In addition, books connect people to larger communities, whether through fandoms, literary circles, or cultural heritage. Readers often form emotional attachments not only to characters but to the shared experience of reading itself. For instance, classic literature binds people across generations, creating a cultural continuity where modern readers engage with the same texts that shaped the past. Similarly, genre-specific communities such as: science fiction and fantasy fandoms allow readers to engage in discussions, fan theories, and creative reinterpretations of beloved works (Jenkins, 2013).

Beyond individual identity, reading also shapes collective identity by preserving cultural narratives and histories. Literature plays a crucial role in national and ethnic identity formation, as seen in postcolonial literature, where authors reclaim histories and voices that were previously marginalised. Books such as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart or Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things allow readers to engage with narratives that reflect the complexities of cultural heritage and historical trauma. This illustrates the broader power of literature, not only as a personal journey of self-discovery but as a means of understanding one’s place within society.

The Psychology Behind Genre Preferences

Reading is not a monolithic activity; different readers gravitate towards different genres based on their psychological needs, cognitive engagement, and emotional fulfilment. Fictional narratives cater to those seeking immersion, imagination, and catharsis, while nonfiction appeals to readers in pursuit of knowledge, self-improvement, or historical insight. Each genre serves a distinct psychological function, shaping how we interact with and interpret the world.

Fiction

Literary Fiction: Intellectual Engagement and Emotional Depth

Literary fiction is often characterised by complex character development, introspective themes, and nuanced storytelling. Unlike genre fiction, which prioritises plot and entertainment, literary fiction demands deeper cognitive engagement and emotional investment. Psychologists suggest that reading literary fiction enhances empathy and social cognition by requiring readers to interpret subtle emotional cues and navigate ambiguous moral dilemmas (Kidd and Castano, 2013).

The open-ended nature of many literary novels forces readers to actively construct meaning, making the reading experience intellectually stimulating. This genre often explores existential themes, human psychology, and societal issues, appealing to those who enjoy introspective and thought-provoking narratives. For example, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) and Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2005) invite readers into the minds of deeply introspective characters, encouraging self-reflection and emotional resonance.

Fantasy & Science Fiction: Imagination and Philosophical Exploration

Fantasy and science fiction attract readers who crave imaginative escapism and speculative thought. These genres create immersive worlds that operate under alternative rules, allowing readers to explore moral, philosophical, and existential "what-if" scenarios. Research suggests that fantasy appeals to those who value creativity, curiosity, and a sense of wonder (Rosenbaum, 2019).

Science fiction, in particular, enables readers to engage with futuristic possibilities and ethical dilemmas, often reflecting contemporary societal concerns through allegory. Works such as George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) or Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) challenge readers to rethink power structures, gender norms, and technological advancements. Similarly, high fantasy novels, such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954), offer narratives of heroism, destiny, and moral struggle, appealing to readers seeking both escapism and ethical depth.

Thrillers & Horror: The Psychology of Fear and Adrenaline

The popularity of thrillers and horror fiction can be explained through the psychology of fear and excitement. Reading suspenseful narratives stimulates the brain’s fight-or-flight response, releasing adrenaline and dopamine, which create a heightened sense of engagement (Clasen, 2017). This controlled exposure to fear allows readers to experience danger and uncertainty in a safe environment, providing both excitement and catharsis.

Thrillers, with their fast-paced narratives and high-stakes conflicts, appeal to those who seek intellectual stimulation and problem-solving challenges. Crime novels, such as those by Agatha Christie or Gillian Flynn, engage the brain’s pattern recognition and deduction abilities, providing satisfaction through the resolution of complex mysteries (Zunshine, 2006). Horror, on the other hand, allows readers to explore their deepest fears—be they supernatural, psychological, or societal—without real-world consequences. The enduring appeal of writers like Stephen King or Shirley Jackson suggests that horror functions as both an adrenaline rush and a form of psychological processing.

Romance: Emotional Fulfilment and Dopamine Release

Romance novels offer readers emotional satisfaction through narratives that emphasise love, connection, and idealised relationships. Studies show that reading romance can increase dopamine levels, the neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward (Regis, 2013). This explains why romance novels, with their focus on emotional connection and happy endings, provide readers with a sense of security and comfort.

Romantic fiction also allows readers to explore different relationship dynamics and emotional experiences in a way that is both immersive and consequence-free. The predictability of romance narratives—where love triumphs despite obstacles—offers a psychological reassurance that real-world relationships often lack. Authors such as Jane Austen, Colleen Hoover, and Nora Roberts have sustained devoted readerships due to their ability to craft compelling emotional arcs that resonate with universal human desires for love and belonging.

Nonfiction

Biographies & Memoirs: Understanding Others and Self-Reflection

Biographies and memoirs allow readers to step into another person’s life, fostering both empathy and self-reflection. Research indicates that reading about others' experiences helps individuals process their own emotions and gain perspective on their personal challenges (Mar et al., 2006). Inspirational memoirs, such as Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom (1994) or Michelle Obama’s Becoming (2018), often serve as guides for resilience, ambition, and self-discovery.

Beyond personal growth, biographies provide historical and cultural insights, giving readers a deeper understanding of influential figures and their impact on the world. This aligns with the human tendency to seek role models and learn from the lives of those who have overcome adversity.

Self-Help & Psychology: The Drive for Control and Self-Improvement

Self-help books cater to the universal human desire for growth, stability, and control over one’s life. The appeal of this genre lies in its promise of actionable change—whether in productivity, relationships, or mental well-being. Studies suggest that reading self-help books can have a placebo effect, creating a sense of progress even before behavioural change occurs (Schwartz, 2018).

Books on psychology and personal development, such as Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) or Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly (2012), help readers understand cognitive biases, emotional intelligence, and resilience. The increasing popularity of these books reflects modern society’s emphasis on self-awareness and optimisation.

History & Science: The Need to Understand the World

History and science books appeal to readers who seek to understand the world’s complexities through a factual and analytical lens. Historical narratives, such as Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens (2011), provide context for modern events, helping readers make sense of political and cultural shifts. The study of history satisfies a fundamental human curiosity about our origins, mistakes, and progress.

Similarly, science books cater to those interested in the mechanics of reality, from astrophysics to neuroscience. Popular science authors like Carl Sagan and Stephen Hawking translate complex theories into accessible narratives, making the pursuit of knowledge both engaging and intellectually fulfilling. The appeal of these books lies in their ability to make readers feel more informed and connected to the broader universe.

The Key Differences Between Fiction and Nonfiction Reading

Reading, whether fiction or nonfiction, is an intellectual and emotional experience shaped by distinct cognitive processes, motivations, and outcomes. While both forms of literature offer value, they engage the brain in fundamentally different ways. Fiction fosters imagination, empathy, and abstract thinking, immersing readers in experiences beyond their own. Nonfiction, by contrast, prioritises logic, factual understanding, and direct knowledge acquisition, appealing to rational thought and intellectual curiosity. Understanding these distinctions reveals why we turn to different genres depending on our psychological and cognitive needs.

Cognitive Differences: Imagination vs. Analysis

One of the most significant differences between fiction and nonfiction reading lies in the way they engage the brain. Fiction activates areas associated with imagination, creativity, and emotional processing. Studies in neuroscience suggest that reading narrative fiction stimulates the default mode network, a brain system involved in mental simulation, perspective-taking, and daydreaming (Tamir et al., 2016). When readers immerse themselves in a novel, they mentally construct the characters, settings, and emotions described in the text, exercising their capacity for abstract thinking.

Moreover, fiction requires readers to infer meaning, interpret subtext, and engage with complex themes. The open-ended nature of many literary works encourages ambiguity and multiple interpretations, fostering critical thinking and intellectual flexibility. In contrast, nonfiction engages the brain’s executive functions, which govern logical reasoning, problem-solving, and factual recall (Graesser et al., 2002). When reading history, science, or philosophy, readers process information analytically, focusing on evidence, argumentation, and the accuracy of claims.

For instance, a reader engaging with George Orwell’s 1984 must interpret allegory, character psychology, and dystopian themes, while someone reading a political history of totalitarian regimes will primarily analyse documented events, patterns, and historical sources. Both require cognitive effort, but the mental pathways activated differ significantly.

Emotional Differences: Immersion vs. Curiosity

Fiction and nonfiction also evoke different emotional responses. Fiction is designed to create deep emotional engagement by drawing readers into the lives of characters, fostering empathy and identification. Psychological research shows that literary fiction, in particular, enhances emotional intelligence by helping readers understand complex human emotions (Kidd and Castano, 2013). The immersive quality of fiction allows readers to experience joy, grief, fear, or hope as if they were part of the narrative.

In contrast, nonfiction tends to evoke emotions through curiosity, intellectual satisfaction, or a sense of discovery rather than direct emotional immersion. While some memoirs or historical accounts may be deeply moving, the primary appeal of nonfiction often lies in its ability to provide knowledge and insight. Readers of science books may feel awe at the vastness of the universe, while those exploring philosophy may experience intellectual excitement rather than emotional catharsis.

For example, reading Pride and Prejudice immerses the reader in Elizabeth Bennet’s world, fostering emotional attachment and personal investment in her fate. By contrast, reading A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking inspires wonder about the cosmos but does not require the same level of emotional identification.

Motivational Differences: Experience vs. Knowledge

The motivation behind reading fiction differs from that of nonfiction. Fiction offers a means of experiencing lives beyond one’s own, allowing readers to step into different perspectives, time periods, and worlds. This is particularly appealing to those who seek escapism, emotional connection, or psychological exploration. Fiction provides a way to temporarily inhabit alternative realities, which can be both entertaining and enlightening.

Nonfiction, on the other hand, is typically read with the goal of acquiring knowledge or practical understanding. Whether it is a self-help book aimed at personal growth, a biography providing historical insight, or a scientific text explaining complex phenomena, nonfiction appeals to readers seeking concrete information. Unlike fiction, which often presents questions without definitive answers, nonfiction generally aims to provide clarity and resolution.

This distinction is evident in how people approach reading choices. A reader picking up Jane Eyre is likely seeking an emotional and narrative experience, while someone choosing Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari is motivated by a desire to understand human history and societal development. Both forms of reading enrich the mind, but they do so in fundamentally different ways.

Conclusion

The act of reading is deeply personal yet universally significant, serving a multitude of purposes that extend beyond mere entertainment. Whether one reads to escape into imaginative worlds, to gain knowledge, or to connect emotionally with human experiences, books offer an unparalleled means of intellectual and psychological enrichment. Fiction and nonfiction alike contribute to shaping our thoughts, expanding our perspectives, and deepening our understanding of both ourselves and the world around us.

The motivations behind reading are as varied as readers themselves. Some turn to books for solace, seeking comfort in the familiar or adventure in the unknown. Others approach reading as a means of self-improvement, drawing wisdom from history, philosophy, or scientific inquiry. Many readers find a sense of belonging in literature, whether through shared cultural narratives, book communities, or the intimate experience of seeing their own emotions and struggles reflected in a story. More often than not, these motivations intertwine—an individual may read for pleasure while subconsciously absorbing new knowledge, or they may seek personal growth through the emotional journey of a novel.

All in all, reading remains one of the most profound ways we engage with the world. It invites us to step outside of ourselves, to challenge our assumptions, and to cultivate both empathy and understanding. In a world increasingly dominated by fleeting digital interactions, books remain a refuge—offering depth, reflection, and meaning. Perhaps the true question is not just why we read, but how the books we choose shape the people we become.

Works Cited

- Carr, N. (2010) The shallows: what the Internet is doing to our brains. New York: W.W. Norton & Company

- Clasen, M. (2017) Why horror seduces. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Graesser, A. C., Singer, M. and Trabasso, T. (2002) 'Constructing inferences during narrative text comprehension', Psychological Review, 109 (3), pp. 371–395

- Green, M. C., Brock, T. C. and Kaufman, G. F. (2004) 'Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds', Communication Theory, 14(4), pp. 311–327

- hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge

- Jenkins, H. (2013) Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. London: Routledge

- Kidd, D. C. and Castano, E. (2013) 'Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind', Science, 342 (6156), pp. 377–380

- Mar, R. A., Oatley, K. and Peterson, J. B. (2006) 'Exploring the link between reading fiction and empathy: Ruling out individual differences and examining outcomes', Communications, 34(4), pp. 407–428

- Nell, V. (1988) Lost in a book: The psychology of reading for pleasure. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Regis, P. (2013) A natural history of the romance novel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- Rosenbaum, R. (2019) Exploring the fantastical: The psychology of imagination and fantasy. London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Schwartz, T. (2018) The power of full engagement: Managing energy, not time, is the key to high performance and personal renewal. New York: Free Press

- Tamir, D. I., Bricker, A. B., Dodell-Feder, D. and Mitchell, J. P. (2016) 'Reading fiction and reading minds: The role of simulation in the default network', Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11 (2), pp. 215–224

- Zunshine, L. (2006) Why we read fiction: Theory of mind and the novel. Columbus: Ohio State University Press

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 300K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.