The Soul of Raskolnikov as a Mirror of Human Contradiction

How Dostoevsky’s Protagonist Reveals the Paradoxes of Our Own Nature

Over 150 years ago, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky published one of the best-known works of Russian literature: Crime and Punishment. First serialised in a literary magazine in 1866, the novel tells the story of Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, a young law student in Saint Petersburg. Since then, readers have repeatedly returned to its central, haunting questions: What drives someone to kill in cold blood? What goes through the mind of a murderer? And what kind of society breeds such individuals? These questions have remained controversial and unanswered for generations, ever since humans began to explore philosophy, logic, and psychology.

In this article, I’m not going to try to answer these questions because, in my view, they don’t have the kind of answer many of us hope to find. Instead, I want to reverse the last question: What kind of society breeds such people? My answer is that it isn’t society that creates them, it is human nature itself. Long before the emergence of societies and civilisations, human beings already carried within them the full spectrum of behaviours and impulses we now try to explain. Society is a product of these behaviours, not the other way around. Societies don’t produce human nature, they contain it, just as they contain people, in all their inevitable complexity and contradictions.

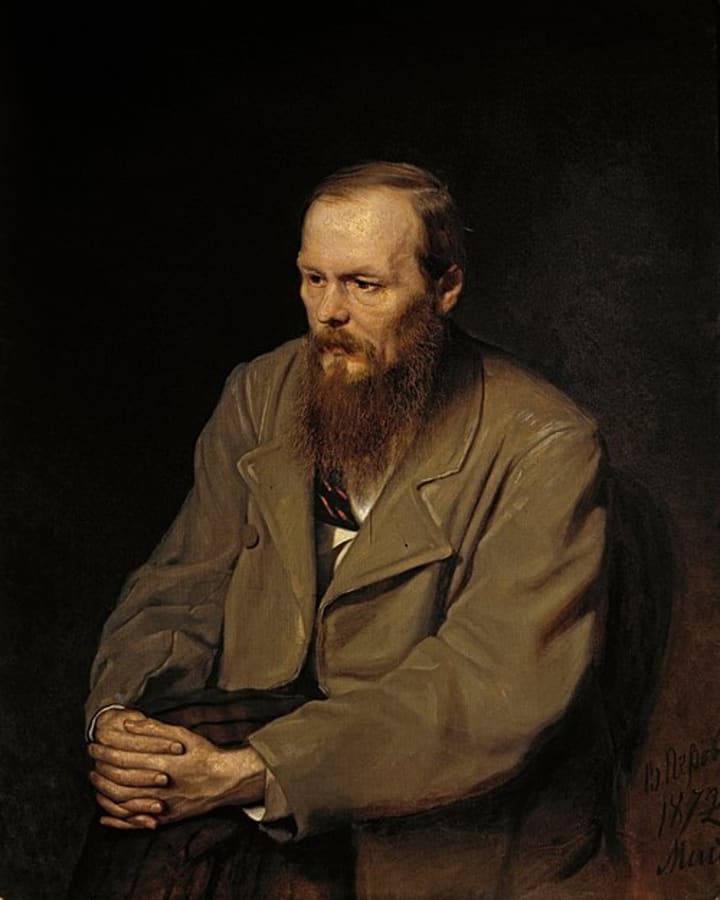

Dostoevsky’s Inner World

"But what about the book?" I hear you ask. Let me first answer a different question: "What about the author?" Dostoevsky, writing in the aftermath of political radicalism, imprisonment, and spiritual transformation, was no stranger to inner turmoil. The Russia of the 1860s was a battleground of ideologies: socialism, nihilism, orthodoxy, and Western liberalism collided in the minds of its thinkers. In this crucible of intellectual and moral tension, Crime and Punishment emerged not merely as a crime story but as a profound philosophical investigation into morality, power, suffering, and redemption.

The Author as Witness to Contradiction

This bleak portrait of Russian society reflects Dostoevsky’s own complex life experiences and evolving ideas. As a young writer who had left behind a promising military career, he was initially drawn to socialism and reform. He joined a circle of intellectuals who met to discuss radical texts banned by the Imperial government. When the group was exposed, its members, including Dostoevsky, were arrested. He spent four harrowing years in a Siberian labour camp before being released in 1854. The experience left him with a far more pessimistic view of social reform and turned his focus toward spiritual and existential concerns. In his 1864 novella, Notes from Underground, he laid out his belief that utopian Western philosophies could never satisfy the contradictory longings of the human soul. Crime and Punishment, conceived and completed the following year, carried forward many of these same themes with even greater psychological and philosophical depth.

Setting the Stage

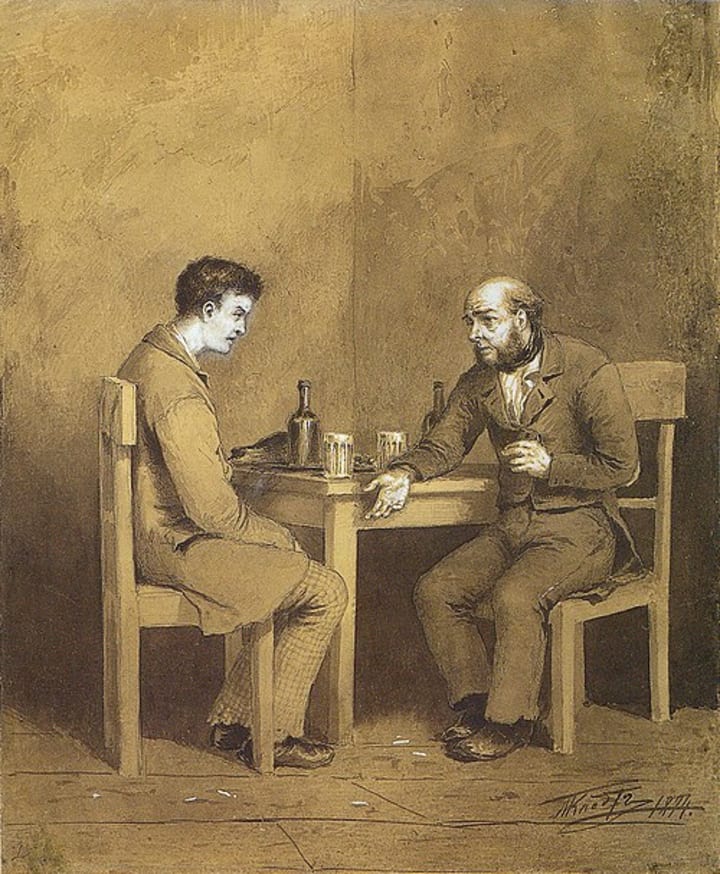

Now that we’ve outlined the profile of the author, we can turn to a brief description of the novel’s context. Set in the sweltering slums of 19th-century St. Petersburg, Crime and Punishment follows the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, a penniless and disillusioned former student who murders an old pawnbroker, convinced that such an act can be justified if it serves a higher purpose. As he attempts to live out his theory of the “extraordinary man,” he becomes increasingly haunted by guilt and existential dread. Surrounding him is a cast of deeply human characters: Sonia, the devout and self-sacrificing prostitute who becomes his spiritual guide; Porfiry, the sharp and psychologically astute investigator who suspects him; Razumikhin, his loyal and kind-hearted friend; and his family, his mother, Pulcheria Alexandrovna, and his sister, Dunya, whose love and suffering intensify his inner conflict. Through these intertwined lives, Dostoevsky constructs a profound psychological and philosophical drama about morality, redemption, and the fractured human soul.

My focus today will be on the book’s protagonist, not to diminish the importance of the other compelling characters, but simply because including a detailed analysis of them all, would require me to write an entire book, not just an article.

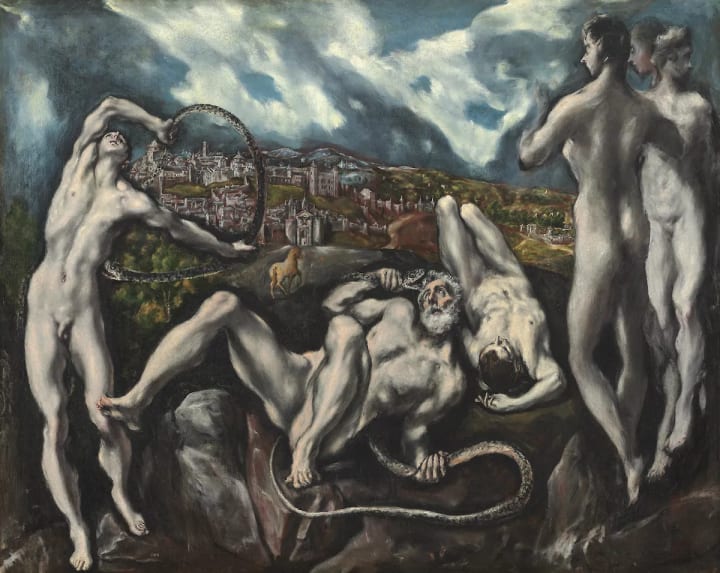

Jesus and the Devil: A Realistic Portrayal of the Human Psyche

What made me truly interested in Raskolnikov is that he embodies an intense polarity: he is both saviour and sinner, both Jesus and the Devil. Allow me this metaphor as an example of the kind of antithesis that Fyodor Dostoevsky himself might have used, raised in a devout Russian Orthodox Christian family and identifying as a Christian throughout his life. In one moment, Raskolnikov donates his last kopecks to a dying man’s family; in another, he commits a brutal double murder. But this is not the inconsistency of a poorly drawn literary character, it is depth. His character represents a refusal to conform to the binary logic of saint versus villain. He is Dostoevsky’s rebellion against moral reductionism.

In Raskolnikov, we find a more honest portrait of humanity: the inner war, the rationalisations, the spiritual yearning, and the arrogance. We see a self that shifts and contradicts, that seeks justification but also desires punishment. To reduce Raskolnikov to a mere moral category would be to miss Dostoevsky’s genius. He is not a cautionary tale; he is a mirror of humanity.

Dialectics of the Self

What emerges from Raskolnikov’s journey is not a linear moral evolution, but a dialectical process. He begins with a thesis, his theory of the extraordinary man. He then confronts its antithesis: the reality of murder and psychological collapse. From this collision, a new self emerges, more humble, spiritually open, and aware of his limitations. This movement mirrors Hegel’s dialectic, where progress unfolds not in straight lines but through contradiction, tension, and synthesis.

The development of selfhood, in this reading, requires both transgression and reconciliation. It is not through purity that Raskolnikov finds meaning, but through rupture. His moral “failures” become necessary waypoints in the formation of a more complete self. Thus, morality in Dostoevsky’s world is not a checklist of actions, but a battlefield of inner forces. Sometimes, to understand what is good, one must encounter evil, not as an external force, but as a part of the self.

On Being Fractured and Human

In the end, Raskolnikov is not exceptional in his contradiction; he is exemplary because he lays bare what most of us conceal. We all house opposites within us. We love and resent. We are generous and cruel. We long for transcendence while clinging to the material. This interplay of opposites is not a flaw of human nature, it is its very structure.

Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher, was among the first to articulate this vision. “The way up and the way down are one and the same,” he wrote. “War is the father of all.” In his view, contradiction was not a sign of failure, but the engine of existence itself. Raskolnikov, then, is not just a man in crisis; he is all of us: fractured, searching, contradictory, and alive.

The Dialectic of Inspiration

Now, as we approach the end of this article, the inevitable questions arise: why did I write this piece? What is the meaning or purpose of briefly sharing my thoughts on the protagonist of one of the most famous novels in the world? Afterall, the questions and ideas I discuss here have been examined, theorised, and answered in many ways before. To this, I return once more to the concepts of inevitability and human nature.

The inspiration for this article came about a month ago after I watched a theatrical adaptation of Crime and Punishment. The play influenced me deeply while staying true to the original story and themes of Dostoevsky’s novel. Perhaps many of you, as readers, have found yourselves compelled to start a book after watching a movie, TV series, or reading an article. For me, this play was the motivation; I hadn’t even realised I needed to read Dostoevsky’s novel until then, and perhaps inevitably, to write this article.

Maybe my subconscious reason for writing this was a desire to encourage others to read the book and undergo the same kind of diagnostic experience I recently went through. Perhaps it was also a search for reassurance and understanding, a feeling of connection in knowing others have wrestled with similar realisations.

The truth is, I have always been fascinated by the Heraclitean, then Nietzschean and Hegelian idea of dialectical contradiction. What I would call the contradiction of existence. Through Raskolnikov’s story, once again, I found these ideas resonating deeply within me.

Written and Published by Sergios Saropoulos

Sources

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Crime and Punishment. (Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Vintage Classics, 1993)

- Frank, Joseph. Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time. (Princeton University Press, 2009)

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morality. (Translated by Carol Diethe, edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson, Cambridge University Press, 2007)

- Heraclitus. Fragments. (Translated by T.M. Robinson, University of Toronto Press, 1987)

- Hegel, G.W.F. Phenomenology of Spirit. (Translated by A.V. Miller, Oxford University Press, 1977)

- Scanlan, James P. “Crime and Punishment: Dostoevsky’s Philosophy of the Self.”

- Morson, Gary Saul. The Genius of Dostoevsky’s Morality.( The New York Review of Books.)

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.