When abuse is inflicted, the pain is not only physical or emotional — it seeps into the mind, warping one’s sense of self, perception of reality, and trust in the world. DARVO, a manipulative tactic identified by Dr. Jennifer Freyd, stands for Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender. This psychological maneuver is a common tool used by abusers to maintain control, shift blame, and avoid accountability.

While much attention is paid to what DARVO is and how it manifests, it is equally important to explore how DARVO affects the mind of the victim. Unlike the fleeting pain of an insult, DARVO’s effects are often prolonged and insidious, especially when experienced over an extended period. The duration of exposure, as well as the relationship between victim and perpetrator, significantly impacts the mental state of the survivor.

Drawing from the insightful analysis of Rev. Sheri Heller, LCSW, RSW in her article, “DARVO: How perpetrators manipulate and control”, this piece will delve deeper into how DARVO shapes the psychological experiences of its victims over time.

The Immediate Impact (A Few Months of DARVO)

For those who experience DARVO for a short time — perhaps in the context of a brief relationship, a new work environment, or an isolated incident — the effects may seem like confusion or self-doubt. But this is not mere “overthinking.” DARVO works by gaslighting the victim, making them question their perceptions of reality.

Imagine confronting a partner about a hurtful comment only to hear:

“I never said that. You’re making it up.”

Or confronting a manager about workplace bullying only to be told:

“You’re just trying to cause drama.”

These statements destabilize the victim’s understanding of reality. The human mind is naturally inclined to seek truth and coherence, so when one’s reality is denied, doubt sets in. This is where self-blame begins. “Did I misinterpret that?” “Maybe I was too sensitive.” This confusion isn’t random — it’s by design.

Self-doubt

One of the most common effects of DARVO is self-doubt, where victims begin to distrust their memory, thoughts, and emotional reactions. This self-doubt arises from the abuser’s persistent gaslighting tactics. For example, when the abuser insists:

“That never happened!”

“You’re imagining things”

The victim is forced to question their perception of reality. Over time, this mental tug-of-war creates cognitive dissonance, where the victim’s memories and lived experiences feel unreliable. Instead of trusting their intuition, survivors seek external validation for things they previously felt certain about. They might ask themselves

“Did I really hear that?”

“Am I blowing this out of proportion?”

This constant self-questioning can erode confidence in decision-making, leaving survivors feeling mentally “foggy” and dependent on others — often the abuser — for clarity and reassurance.

Anxiety

Anxiety is another pervasive mental effect of DARVO. The core of anxiety in this context stems from the inconsistency between the victim’s understanding of events and the abuser’s deliberate distortion of those events. This mental dissonance produces a state of unease, as the victim is caught between what they know to be true and what they are told to believe.

The body responds to this confusion with a surge of adrenaline, as it attempts to resolve the perceived threat. Survivors may experience racing thoughts, insomnia, rapid heartbeat, and an inability to “calm down,” even in moments of stillness.

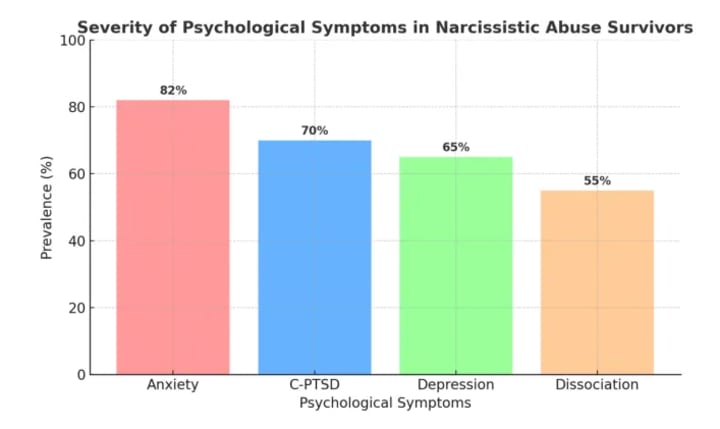

“78% of victims reported experiencing severe anxiety, making it one of the most prevalent psychological symptoms associated with DARVO.” — Vidyut Singh, 2024.

This anxiety is not confined to the moments when the abuser is present; it often extends into the survivor’s daily life, making it difficult to focus on work, relationships, and personal well-being.

Hypervigilance

Another lasting mental effect of DARVO is hypervigilance, a heightened state of awareness where survivors become excessively attuned to the moods, behaviors, and body language of the abuser. This is a survival mechanism that develops when victims feel they must “read the room” to avoid conflict, blame, or punishment.

Hypervigilance can manifest as scanning for danger, anticipating outbursts, or feeling on edge even in calm situations. Survivors may become sensitive to small cues like tone of voice, subtle changes in facial expressions, or shifts in body language. While this heightened awareness is useful in avoiding immediate danger, it comes at a cost. It keeps the body in a state of chronic stress, leading to physical symptoms like headaches, muscle tension, and fatigue.

Over time, the constant “fight-or-flight” response weakens the nervous system, making it difficult for survivors to return to a baseline state of calm. Singh’s research points out that hypervigilance is a key indicator of C-PTSD, which is a common outcome for survivors of prolonged DARVO. Even after leaving the abusive situation, survivors may continue to “scan” for danger in new environments, making it hard to relax or trust that they are safe.

These symptoms may sound mild in isolation, but they are precursors to larger mental health struggles if the DARVO continues for an extended period.

The Mid-Term Impact (Several Months to 1–2 Years of DARVO)

As DARVO continues, the effects become more entrenched. The victim may still be in the relationship or the toxic environment, or they may have left but are grappling with its psychological aftershocks. At this stage, the mind begins to adapt to the abuse. This period is when cognitive dissonance becomes a defining feature of the victim’s experience.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance refers to the psychological discomfort that occurs when one holds two conflicting beliefs. For a victim of DARVO, the contradiction might sound like:

“They love me, but they also hurt me.”

“My manager says I’m incompetent, but I have glowing reviews from clients.”

To resolve this discomfort, the mind often seeks to reduce tension, and sadly, the mind tends to side with the abuser. Why? Because it’s easier to shift one’s belief system than to face the unsettling reality that someone you trust is harming you.

Internalized Self-blame

Over time, victims begin to believe that they are responsible for the abuse they endure. This occurs because the abuser’s denial and blame-shifting tactics force the victim to search for fault within themselves. Statements such as:

“You’re always overreacting”

“You’re the one causing all the problems”

Cause victims to question their behavior, thoughts, and reactions. Instead of recognizing the abuser’s manipulation, victims may think:

“Maybe I am too sensitive”

“Maybe it is my fault.”

As self-blame becomes habitual, it becomes deeply ingrained in the survivor’s psyche. This internalized narrative of personal failure can have long-term effects on self-esteem, self-worth, and decision-making, often making it difficult for victims to advocate for themselves in future relationships or professional environments.

Imposter Syndrome

Another significant mental effect of DARVO is the emergence of imposter syndrome. Victims subjected to constant doubt, discrediting, and attacks on their character start to believe that they are “fooling” people into thinking they are competent, capable, or deserving of success. This happens because the abuser’s attacks on their intelligence, competence, or motives wear down their confidence.

In cases of workplace harassment, for example, abusers may claim that the victim is “incompetent” or “difficult to work with,” despite the victim having a history of positive performance reviews. Over time, these accusations chip away at the victim’s sense of accomplishment, causing them to doubt their skills. When success does come, survivors often dismiss it as luck or trickery, thinking:

“I didn’t really deserve this.”

This can lead to self-sabotaging behaviors, where survivors intentionally underperform to avoid being “exposed” as a fraud.

Isolation

Victims often withdraw from friends, family, and support networks. This isolation is fueled by two key factors: shame and fear of disbelief. Since DARVO operates by reversing victim and offender roles, survivors are frequently framed as the “troublemakers” in the eyes of others. When survivors seek support from loved ones, they are sometimes met with skepticism or are told to “move on” or “forgive.”

This invalidation can be emotionally devastating, leading survivors to conclude that it is safer to remain silent than to risk being blamed again. As a result, they retreat from social interaction, stop reaching out for help, and endure the abuse in isolation. This isolation not only makes it harder for them to escape the abusive situation but also reinforces the abuser’s control over them, as they become more dependent on the abuser for emotional validation.

Chronic Guilt

This guilt stems from the abuser’s portrayal of themselves as the “real victim” and the actual victim as the “aggressor.” Abusers frequently weaponize guilt by saying things such as:

“After all I’ve done for you, you treat me like this?”

“You’re making my life miserable with your accusations.”

These statements shift attention away from the abuser’s actions and place an emotional burden on the victim. Over time, the survivor feels as though they must “atone” for the harm they supposedly caused. This chronic guilt often persists even after the victim leaves the abusive situation, as the abuser’s voice is internalized within the survivor’s mind.

Victims may continue to apologize excessively in future relationships, avoid confrontation, and downplay their own needs to prevent “hurting” others. This misplaced sense of responsibility often requires trauma-informed therapy to unlearn, as it can linger for years after the abuse has ended. A powerful example can be seen in toxic family dynamics. A parent might say:

“After all I’ve done for you, how dare you accuse me of being abusive?”

The child, still dependent on the parent for emotional or physical survival, internalizes the belief that they are selfish for speaking up. Over time, this “selfish” label shapes their self-image, often leading to a fear of asserting boundaries well into adulthood.

The Long-Term Impact (Years of DARVO Exposure)

Long-term exposure to DARVO is comparable to being exposed to a slow-release psychological poison. Victims who have experienced DARVO for years to decades. Often familial abuse, romantic entanglements with narcissists, or systemic workplace harassment — are forced to endure an erosion of their mental health.

According to Vidyut Singh’s research, victims exposed to long-term narcissistic abuse often develop symptoms similar to complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD).

“78% reported symptoms of severe anxiety, while 65% exhibited signs consistent with C-PTSD.” — Vidyut Singh, 2024.

Prolonged exposure to DARVO does not merely leave emotional scars — it rewires the brain’s threat response system. Victims are frequently trapped in a state of hypervigilance, constantly scanning their environment for signs of danger. This heightened state of alertness is linked to the overactivation of the amygdala, the brain’s fear-processing center, and the reduced functioning of the prefrontal cortex, which governs rational thinking and decision-making. As a result, survivors may experience difficulty concentrating, making decisions, or feeling safe in situations where no threat exists.

Singh’s study also notes the emergence of self-gaslighting, where victims begin to doubt their memories, perceptions, and instincts. This is a direct consequence of prolonged exposure to gaslighting and manipulation. This cycle of self-doubt perpetuates dependence on the abuser and can make it even harder for survivors to break free from toxic environments.

Key Mental Effects:

- Loss of Identity: Victims lose sight of their authentic selves as they conform to the abuser’s expectations.

- Emotional Numbness: Feelings of hopelessness and detachment from one’s emotions are common.

- Depression & Suicidal Thoughts: The mental exhaustion of constantly being blamed, disbelieved, and isolated can lead to depressive symptoms.

- Persistent Intrusive Thoughts: Victims replay arguments, accusations, and their perceived “failures” over and over.

- Difficulty Trusting Others: Once the mind has learned that “no one will believe me,” it becomes difficult to trust future friends, partners, or therapists.

Victims may feel as though they are “going crazy.” But this is not a mental illness in a vacuum — it is a logical reaction to years of manipulation and mental warfare. In extreme cases, victims experience dissociation, where they “check out” mentally to avoid dealing with reality.

How To Heal From DARVO’s Effects

Healing from DARVO requires more than time. It requires conscious unlearning. If a victim has spent months or years internalizing blame and doubt, they need to work on reversing those patterns.

- Name the Abuse: Victims often can’t begin healing until they recognize they were abused. Learning about DARVO is often an “aha” moment, where survivors realize, “This happened to me.”

- Reclaim Reality: Therapy (especially trauma-focused therapy) is crucial for grounding survivors back in objective reality. Therapists must validate the victim’s experiences rather than playing “devil’s advocate.”

- Rebuild Trust in Self: Victims must relearn how to trust their intuition. It might start with small acts, like trusting their gut on minor decisions, eventually scaling to bigger choices.

- Set Boundaries with Perpetrators: If possible, cutting off or reducing contact with the abuser helps prevent further manipulation.

- Seek Trauma-Informed Therapy: Singh highlights the benefits of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for survivors. These therapies help reprocess traumatic memories and reframe negative self-beliefs.

Reclaiming the Mind

DARVO is not only a tactic of deflection and gaslighting — it is a tool of mental entrapment. By making victims doubt their reality, question their worth, and assume blame for their suffering, perpetrators achieve control. But control can be broken.

Rev. Sheri Heller’s analysis of DARVO emphasizes that understanding these tactics is a step toward liberation. For survivors, learning to recognize DARVO is like finding the key to a long-locked door. Once victims name the abuse, they can begin reclaiming their minds, their sense of self, and their reality.

The mind, once entangled, can be untangled. It is not easy, but it is possible. Through therapy, education, and support, survivors of DARVO can reframe the narrative. No longer the “aggressor” or “troublemaker,” they can become what they were all along — the truth-tellers.

If you or someone you know has experienced DARVO, know that it is not your fault. Resources and support are available.

About the Creator

Tania T

Hi, I'm Tania! I write sometimes, mostly about psychology, identity, and societal paradoxes. I also write essays on estrangement and mental health.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.