Minority groups in the U.S. have spent their lives fighting for inclusion in American Society, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered (LGBTQIA+) community is no exception. Many young members of the community begin their search for self in a public or academic library. What gets learned is a huge part of what shapes our lives for a very long time.

It is so important that an accurate portrayal of LGBTQIA+ life be accessible to anyone. That portrayal should be human, exploring both the positive and negative aspects of LGBTQIA+ life. Library Science is a service organization that could supply information to all of the public, not just a select few, but history has shown that even in Library Science the LGBTQIA+ community holds the position of outsider, whose needs are barely addressed in public society.

Our American Library history is built on the same patriarchal conservatism that exists in all American institutions. Although 80% of the library profession is female, the higher managerial administrative positions are more often than not, given to men. Through the 1800's to the 1940's, the patriarchal conservatism within library science made it especially easy to control dissenting voices within the profession.

Because the view of library professionals was always ahistorical, we are just now discovering some of those dissenting voices, and are able to look at how their voices were silenced within the organization. Many of these voices were women. Some men in charge operated within the system to maintain a patriarchy that left many groups of people out (Hildebrand).

Early library professionals, much like professionals of today, focused on the needs of the patron. That early focus was the sole approach to the profession, so very little has been written about library professionals, or about the issues that affected them. While a great deal was written on issues concerning the patron, unfortunately those concerns were toward the white patron only.

People of color, and LGBTQIA+ individuals did not get a large focus except as potential problem situations. It took black groups to force the issue of collections geared to the black patron and it has taken forces from the LGBTQIA+ community to get libraries to go beyond the negative materials that have always been available.

As LGBTQIA+ individuals were represented only as sick, perverted, or criminally deviant, it became necessary for the community to tell the truth about themselves, and to record that truth for others.

Unfortunately, just after WW2, and through the 1950's, a new fear swept the nation. McCarthyism highlighted fear of the “other,” and drove people to destroy each other before they even learn who they are.

Fear of difference created a new degree of patriotism that vowed to eliminate "the other" "the traitor.” It was a call to destroy any non-capitalistic non-democratic point of view. Loyalty swept the country. Pride, patriotism, and fervor allowed McCarthyism to destroy the lives of those who would question how the United States did things.

This meant anyone not a member of white dominant heterosexual society could be called into question. Anyone who questioned any aspect, (including capitalism), was high on the list.

Communists and LGBTQIA+ members were actively pursued (Robbins). Library professionals, along with other government employees were scrutinized for their personal beliefs. Some were purged from the service; suffered prison time, and even personal attacks.

McCarthyism attacked every American by spreading homophobic views to the nation's citizens. Government documents state that “by "enticing” normal people to engage in “perverted practices" homosexuals were a "corrosive influence” on their colleagues (Gough). It was often said that [...] One Homosexual ...can pollute an entire government office."

These constructed mainstream ideals presented homosexuals in the most negative connotations possible, and forced them out of all professions including library science. This period of only negative information about homosexuality lasted well into the 1970's.

But the revolutions of the 1960's, lead to a challenge of patriarchal traditions in the 1970's. Library Science was the first profession where members of the profession forced the profession to re-evaluate itself, and question what its mission and function really was.

The Social Responsibilities Round Table was born, and became an umbrella group for the problems of society that were often also a part of problems for the library profession. Questions of racism, sexism, and classism were looked at. Caucus groups were formed.

The Women's caucus, the Black caucus, and The Task Force on Gay Liberation were formed in the early 1970's. Of all these groups, only The Task Force on Gay Liberation was made up of members of the LGBTQIA+ community who never served as library professionals after they joined the task force, even though some of them had been in the library profession long before their (Gittings).

After 1970 many new philosophies and approaches to the job were espoused, and unofficially many were followed, especially when questioning issues about censorship, and homophobia in cataloguing by way of subject headings. Those were the fields most attacked during the seventies, and great strides were made in the renaming of issues pertaining to homosexuality.

The words Homosexual and Lesbian were added, recognizing for the first time, the individuals who made up a newly acknowledged group of people. Later the terms Gay and Queer would also be added as possible subject headings (Carmichael). Many librarians voiced the idea that it was the librarian's duty to fight censorship, and follow the idea that the library is by nature, a place of controversy (West).

A look at how long it took dissenting voices to see corresponding action within the profession, can be seen in a look at the evolution of the Gay Liberation Task Force. It clearly shows how homophobia and patriarchy manages to slow down the progress of our organizations.

It was not until 1986 that the word lesbian was added to the title to become the Gay and Lesbian Task Force. The prefix Bi was not added until 1994 to address Lesbigay issues. Transgendered members of the community had just barely been recognized."

These additions occurred only after the words themselves became official Library of Congress subject headings. This is the official acknowledgment of mainstream admission of our existence as part of the American public.

It was not until the late 1980's that the majority of mainstream libraries and archives actively began to seek out gay and lesbian collections. It is argued by most gays and lesbians that this is a fad that could conceivably end as abruptly as it began, and if that happens the collections may disappear, along with their intent to represent a minority group who is always under represented. This has a tremendous effect on both the LGBTQIA+ user and the LGBTQIA+ professional.

Mainstream libraries and archives currently tend to focus on famous persons or those connected to famous persons, and do not accurately reflect the gay and lesbian population as it really exists. It leaves out the story of the average LGBTQIA+ community member.

So does the restricted access in academic libraries, which leaves out a large portion of the non-academic public (Nestle). It makes it hard for the average LGBTQIA+ member to find good information about themselves. This does a great disservice to young users just beginning to question their sexuality.

To do research on LGBTQIA+ issues you must talk to librarians and archivists. A patron's early experience can be greatly influenced by the homophobia of a library professional. Since library professionals are not trained to deal with minority groups as patrons, they can scare off potential long-term users by their attitudes.

LGBTQIA+ patrons also find that materials they are searching for are not on the shelves and don't seem to be checked out. Getting a professional to help find them can be difficult, especially if the professional lacks the sensitivity and experience necessary to respond to special needs and controversial subjects. In some cases though, homophobia causes reference librarians to tell individuals that the materials they are looking for simply don't exist.

What that fear has done is "silence, hide, marginalize, and devalue gay and lesbian lives and issues." LGBTQIA+ professionals are subjected to all the problems that any patron is subjected to, but in addition, they bear the burden of fighting for inclusion of LGBTQIA+ issues on the job. They fight homophobia in cataloguing, acquisitions, patron services, and as an out activist within the library profession.

Since librarians have always put the needs of the patron first, the beginning of LGBTQIA+ activism was fought in the realm of Cataloging and Subject Headings. It took massive amounts of work to change subject headings so that researchers could find information that pertained to them. LGBTQIA+ librarians still fight to make catalog cross-references more LGBTQIA+ friendly.

One issue still a problem in many archives is that the sexuality of a subject has been left unrecognized by professionals. Lovers and couples are not cross-referenced, which makes tracking down letters and documents next to impossible unless you already know who couples were (Marston).

Acquisitions is an especially troubling area. If the books aren't bought, they aren't going to be available to users. Several arguments are used by homophobic acquisitions clerks: 1) There isn't enough money in the budget to pursue minority collections. 2) They try to find books but there isn't enough information on LGBTQIA+ publications. That means it takes up too much of the business day to find LGBTQIA+ books that can be purchased. 3) There is no gay community in a particular location. No one asks for that kind of material, so none is needed, because there are no LGBTQIA+ patrons, or not enough to warrant major purchases (Marston).

LGBTQIA+ professionals have argued that there is also a tremendous lack of training in LGBTQIA+ issues for the professional to be. A [1995] national survey of library school graduates [...] found that nearly half of them had not received any information about lesbigay issues in their library education programs" (Gough).

Library school students suggest that their experience is influenced by professional paranoia. Students who suggest that they want to pursue LGBTQIA+ issues, are led away from that research, and sent into other directions. Some are told outright: you can't do that type of research until you have tenure, otherwise you will have no academic career.

Cornell University Human Sexuality Collection, archivist Brenda Marston, tells how she was told that her primary research materials did not exist, and it was only after graduating from Graduate School that she found materials were out there.

It is currently up to LGBTQIA+ librarians within institutions [to] shape collection development policies and provide broad-based, high quality reference service" (American Libraries). They must “educate and challenge policy makers.”

Unfortunately this is too tall an order to lay on the shoulders of LGBTQIA+ professionals. “Many people who work for organizations perceived as progressive find that within those institutions, critical voices are often muted." Many LGBTQIA+ professionals find that this is a common experience (Nestle).

The fad position of the LGBTQIA+ community, and the continuing homophobia in the profession, makes people wary as to how long the fad will last. They question what will happen when mainstream collections decide that funding cuts will not allow them the luxury of collecting minority groups, and they move toward generic (white/mostly male) work as representative of all Americans.

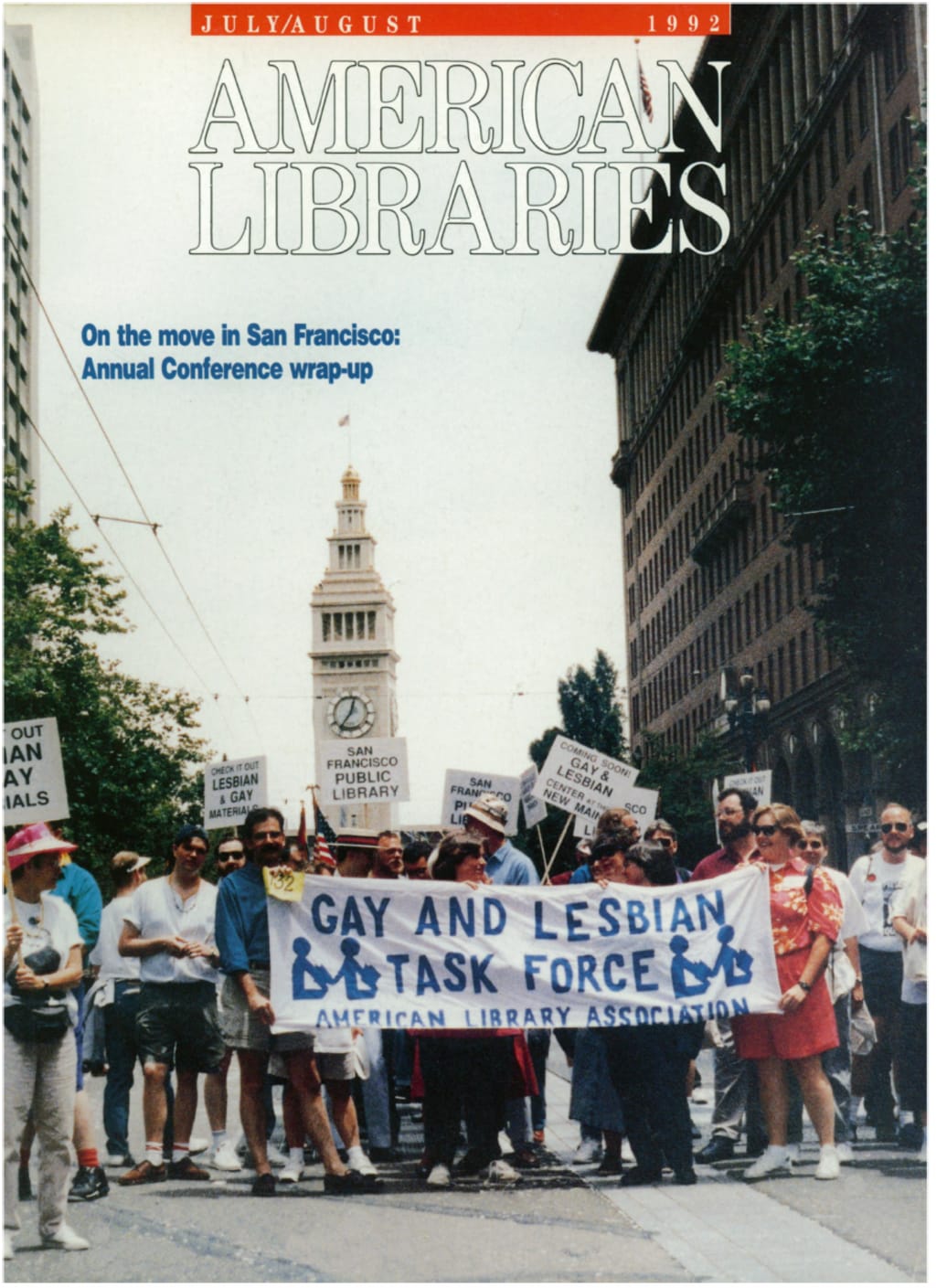

The depth and breadth of bigotry and homophobia in the library profession publicly became known in 1992 when the American Libraries magazine put a photo of the ALA Gay and Lesbian Task Force marching in a San Francisco Gay Pride parade (Gittings) The stream of letters that poured in from August to December of 1992 is an example of what the few LGBTQIA+ librarians were faced with.

There were a number of letters of support, but the homophobia expressed with extreme venom shows what librarians are truly up against an a typically conservative institution that by its very nature, should be controversial (Baum).

These problems lend credence to many straight women and lesbians who argue for the maintenance of both mainstream and individual / community collections. One of the non-mainstream holdouts has been The Herstory Collection in New York. Joan Nestle and LHEF members have been adamant that mainstream collections will continue to hide, marginalize, and suppress women until patriarchy is no longer a part of American institutions (Library Journal).

Within the library / archive professions both lesbians and straight women are indeed hidden. They are hidden among other subject headings, through bad cross referencing, identity issues, and racial issues. Lesbians in particular are hidden between gay men's books, women's books, identity issues, and materials on racial issues (Flowers).

Nestlé’s mantra has been Audre Lorde’s quote: “The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house." She maintains that only the end of patriarchy will bring about a change in our attitudes and our institutions. For Nestle, and many other women, that "separatism preserves integrity, ensures safety, and exercises the collective will (Carmichael)."

A great deal of women's research supports Nestle's separatist stance. Just by looking at women in the profession since 1970, we get a sense of how long progress takes inside conservative institutions. In 1970, a committee urged a creation of a committee on the status of women, it wasn't until 1975 that the committee was approved by the ALA Council, and then formed (Marston, Carmichael, Kester).

In the 1990's life did not make significant changes for women and lesbians. A 1995 equity study by Doris Flowers and Pamela Lepage called “Whose Personal Stories Are Published in Education Journals?” found that subtle influences keep institutional women out of the loop. Other results indicated that “personal experience stories written by men have been published more often than those by women.

Until changes in attitudes of the professional lead to a non-homophobic, hassle-free environment, we may have to continue to look to individual and community collections for the truth of our existence.

Marston, Nestle, and many other women have emphasized time and time again that the need to connect, to network, will bring LGBTQIA+ collections together, and that support alone, may save collections that can no longer be operated by individuals on their own. It may also encourage every LGBTQIA+ individual to record their history for others. The good news is that Cyberspace offers minority groups a connection to others that did not exist in the past.

This acknowledgment that others are out there in the world and willing to share information and experiences, may be able to help sustain all minority groups until institutions can re-think and change the way they currently operate.

Bibliography

“AL's Gay Pride Cover Pro... Con.” American Libraries. November 1992. 840-42.

Baum, Christina. Feminist Thought in American Librarianship. Jefferson NC: McFarland, 1992.

Carmichael, James V. Daring To Find Our Names: The Search For Lesbigay Library History._Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1998.

“COSWL: Prospects at Age 21.” Library Journal. March 1, 1997.

Duggan, Lisa. “History's Gay Ghetto: The Contradictions of Growth in Lesbian and Gay History.” Presenting the Past: Essays on History and the Public. Ed. Susan Porter Benson, Stephen Brier, Roy Flower Rosenweig. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1986. 281-90.

Freedman, Estelle B. “The Burning of Letters Continues” Elusive Identities and the Historical Construction of Sexuality.” Journal of Women's History Vol. 9 No. 4. Winter 1998. 181-200.

“Gay/Lesbian Authors Appraise family Values" American Libraries. September 1992. 635-36. "Gay and Lesbian Archives” American Libraries. November 1992. 872.

Gittings, Barbara. “Gays In Libraryland: The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First Sixteen Years.” Daring To Find Our Names: Ed. James V. Carmichael. 81-94.

Gaughan, Tom. “The Last Socially Acceptable Prejudice." American Libraries. September, 1992. 612. 2 612

Gough, Cal and Ellen Greenblatt. Gay and Lesbian Library Service. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1990.

Guttag, Bianca. “Homophobia In Library School.” Revolting Librarians. Celeste West 1973.

Heim, Kathleen (Ed). The Status of Women In Librarianship: Historical, Sociological, and Economic Issues. New York: Neal Schuman, 1983.

Hildenbrand, Suzanne (Ed.). Reclaiming the American Library Past: Writing the Women In. Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1996.

"From the Politics of Library History To the History of Library Politics.” Reclaiming the American Library Past: Ed. Hildenbrand. 1 Johson Cooper - See End Notes

Kester, Norman. Liberating Minds: The Stories and Professional Lives of Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Librarians and Their Advocates. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1997.

"Lesbigay Librarians Share Their Stories." American Libraries. June/July 1997

"Queer Histories: Queer Librarians: The Historical Development of a Gay Monograph.” Daring To Find Our Names: Ed. James V. Carmichael. 65-80.

Kniffel. Leonard. “You Gotta Have Gerber-Hart: A Gay and Lesbian Library For the Midwest.” American Libraries. November 1993. 958-60.

Loverich, Patricia and Darrah Degnan. “Out On The selves? Not Really.” Library Journal. June 15, 1999.

Marston, Brenda. “Archivists, Activists, And Scholars: Creating A Queer History.” Daring To Find Our Names: ed. James V. Carmichael. 135-152. Nestle, Joan and LHEF Inc. “Lesbian Herstory Archives.” 1997.

http://www.datalounge.net/network/pages/lha/ (December 6, 2000).

Pritchard, Sarah. “Backlash, Backwater, or Back To the Drawing Board? Feminist Thinking and Librarianship in the 1990's.” Wilson Library Bulletin. June 1994.

"Reader Forum” American Libraries. July/August 1992. 552.

“Reader Forum.” American Libraries. September 1992. 625. "Reader Forum." American Libraries. October 1992. 738-40.

Rimpau, Ina. “Carnal Knowledge and the Librarian." Liberating Minds: Ed. Kester. 126-28.

Robbins, Louise S. “A Closet Curtained By Circumspection: Doing AB Research on McCarthy Era Purge of Gays from the Library of Congress.” Daring To Find Our Names. Ed. James V. Carmichael. 55 64.

Schwarz, Judith. “The Archivist's Balancing Act: Helping Researchers While Protecting Individual Privacy.” The Journal of American History. June 1992.

Strippling, Sherry. “A History Comes Out Of the Closet—Mainstream Groups Vie For Gay and Lesbian Archives To Help Tell the Whole Northwest Story.” The Seattle Times. October 3, 1999.

West, Celeste, Elizabeth Katz etc. Revolting Librarians. San Francisco, CA: Bootlegger,1973.

Wolfe, Steve. “Sex and the Single Cataloger: New Thoughts On Some Unthinkable Subjects.” Revolting Librarians. 1973.

About the Creator

CL Robinson

I love history and literature. My posts will contain notes on entertainment. Since 2014 I've been writing online content, , and stories about women. I am also a family care-giver.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.