Painting Through Pain

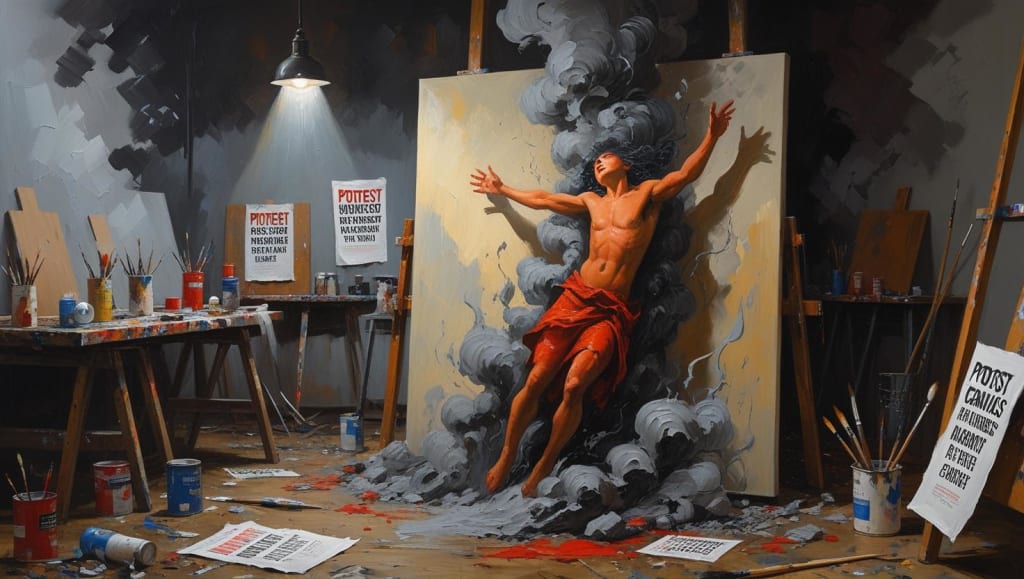

I stood in a cramped basement gallery last month, staring at a canvas by Perla Santiago, a contributor to Salt in the Wound. The painting was raw—swirls of crimson and ash gray, a figure clawing upward from a scorched earth, its face half-formed but screaming life. It wasn’t just art; it was a wound laid bare, a howl of grief turned into color. Perla, a Chilean artist who lost her brother in the 2019 protests, painted it during a blackout, using scavenged pigments mixed with tears. In Salt in the Wound, a zine collecting dispatches from artists in crisis, visual art like Perla’s holds beauty and pain in the same breath. This is the story of how artists paint through grief, transforming loss into something that refuses to be forgotten.

The Alchemy of Grief

Grief is a heavy thing, shapeless and suffocating. For visual artists in Salt in the Wound, painting is a way to give it form, to wrestle it onto a canvas where it can be seen, felt, held. These artists—working in war zones, protest camps, or exile—create amidst personal and collective loss. Their work isn’t about escape; it’s about confrontation, a refusal to let grief consume them whole.

Perla Santiago’s story is one of many. Her brother, Mateo, was killed during Chile’s estallido social, caught in a police crackdown. “I didn’t know how to keep living,” she told me over a grainy video call. “But I knew how to paint.” Her contribution to Salt in the Wound, a series of illustrations called “Ghosts of Santiago,” shows faceless figures marching through tear gas, their silhouettes glowing with defiance. Each stroke is heavy, layered with rage and love. “Painting him keeps him here,” she said. “It’s my way of saying he didn’t die for nothing.”

Another artist, Ellis_DA, paints from a refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. A Rohingya survivor, Ellis lost their family in Myanmar’s 2017 genocide. Their work in Salt in the Wound—ink sketches of burning villages and outstretched hands—feels like a fever dream. “I draw what I can’t say,” Ellis told a zine editor, their words translated from Rohingya. “My pencil is my voice.” Using charcoal scavenged from cooking fires, Ellis creates on scraps of cardboard, their art a testament to survival.

Art as a Vessel

Why paint through pain? Art doesn’t undo loss or stop violence. Yet for artists like Perla and Ellis, it’s a vessel for what words can’t hold. A canvas can carry contradictions—beauty and horror, despair and hope—without resolving them. “Grief isn’t linear,” Perla said. “Painting lets me live in the mess.” Her canvases, smeared with violent reds and soft golds, feel alive, as if Mateo’s spirit pulses through them.

In Salt in the Wound, visual art is a witness to suffering. Ellis_DA’s sketch “Mother’s Shadow” shows a woman cradling a child against a backdrop of flames. Shared in the zine, it was later projected at a human rights vigil in Dhaka, its stark lines moving strangers to silence. “I want people to see what we lost,” Ellis said. Their art doesn’t just mourn; it demands accountability, forcing viewers to confront atrocities the world prefers to ignore.

Art also preserves memory. Perla’s “Ghosts of Santiago” immortalizes the 2019 protests, capturing faces and moments that news cameras missed. One illustration shows a protester’s bandana, soaked in vinegar against tear gas, fluttering like a flag. “I paint so we don’t forget,” she said. In a world quick to move on, art like hers is a stubborn reminder of what was lost—and what’s still at stake.

The Cost of Creation

Painting through grief is not gentle. It’s a brutal act, ripping open wounds to let them bleed onto the canvas. Perla described nights spent sobbing over her work, each brushstroke a memory of Mateo’s laugh or his bloodied jacket. “It hurts to paint,” she admitted. “But it hurts more to stop.” Ellis_DA’s sketches are drawn in stolen moments, their hands trembling from hunger or fear. “Sometimes I hate my drawings,” they confessed. “They make me relive it. But I can’t let those memories die.”

Materials are another hurdle. In crisis zones, paint is a luxury. Perla mixes house paint with dirt, her palette limited to what she can scavenge. Ellis uses charcoal and ink made from boiled plants, their “canvas” often the back of aid flyers. Both work in unstable conditions—Perla during blackouts, Ellis under monsoon rains that threaten to smear their ink. Yet these constraints shape their art, giving it a raw, tactile urgency. “The imperfections are the point,” Perla said. “They show what we’re up against.”

There’s also the danger of visibility. In Chile, Perla’s protest art has drawn police scrutiny; her studio was raided last year. Ellis_DA’s sketches, smuggled out of the camp, could mark them as a target if traced back. “I’m scared,” Ellis admitted. “But silence is worse.” Their art is an act of courage, a refusal to let fear snuff out their voice.

Beauty in the Breakage

Standing before Perla’s canvas in that basement gallery, I felt my chest crack open. Her painting wasn’t beautiful in a conventional sense—its colors clashed, its lines were jagged—but it was alive with a fierce, haunting beauty. Art like hers, or Ellis_DA’s, holds a truth: grief and beauty coexist. A painting can be a wound and a balm, a scream and a prayer. “I paint to find the light,” Perla said. “Even if it’s just a flicker.”

In Salt in the Wound, this light flickers across pages. Perla’s illustrations sit beside Ellis_DA’s sketches, each piece a fragment of a larger story. They’ve inspired others—Perla’s work sparked a mural project in Valparaíso, while Ellis’s sketches were reprinted in a solidarity zine in Malaysia. “I didn’t expect anyone to see my drawings,” Ellis said. “Now they’re carrying my people’s pain to the world.” Art, in its quiet way, amplifies voices that power tries to crush.

Philosopher Elaine Scarry wrote that beauty demands we act, that it pulls us toward justice. The art in Salt in the Wound does this. It doesn’t solve grief or end oppression, but it humanizes, connects, provokes. It says, “Look at this pain. Now do something.” Perla’s canvases, Ellis_DA’s sketches—they’re not just art. They’re calls to arms, painted in the colors of loss.

Keep Painting

As I write this, I’m haunted by Perla’s half-formed figure, rising from ashes, and Ellis_DA’s inked hands, reaching through flames. Their art is proof that grief doesn’t have the final word. To paint through pain is to claim life, to insist on creating even when the world crumbles. It’s not enough to stop wars or heal wounds, but it’s something—a spark, a memory, a refusal to disappear.

Salt in the Wound is a gallery of such refusals. Its artists, with their scavenged paints and trembling hands, show us that creation is resistance. They paint not to escape grief, but to live with it, to make it bear witness. So here’s the call, to them and to us: Keep painting. Keep drawing. Keep making, no matter the cost. The canvas is waiting, and the world needs your grief’s fierce beauty.

About the Creator

Shohel Rana

As a professional article writer for Vocal Media, I craft engaging, high-quality content tailored to diverse audiences. My expertise ensures well-researched, compelling articles that inform, inspire, and captivate readers effectively.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.