The University of Whispers: How Librarians and Students Defeated a Regime

In 1970s Poland, history was a lie and truth was a crime. So, they built a university that didn't exist—in living rooms, basements, and the shadows of the secret police

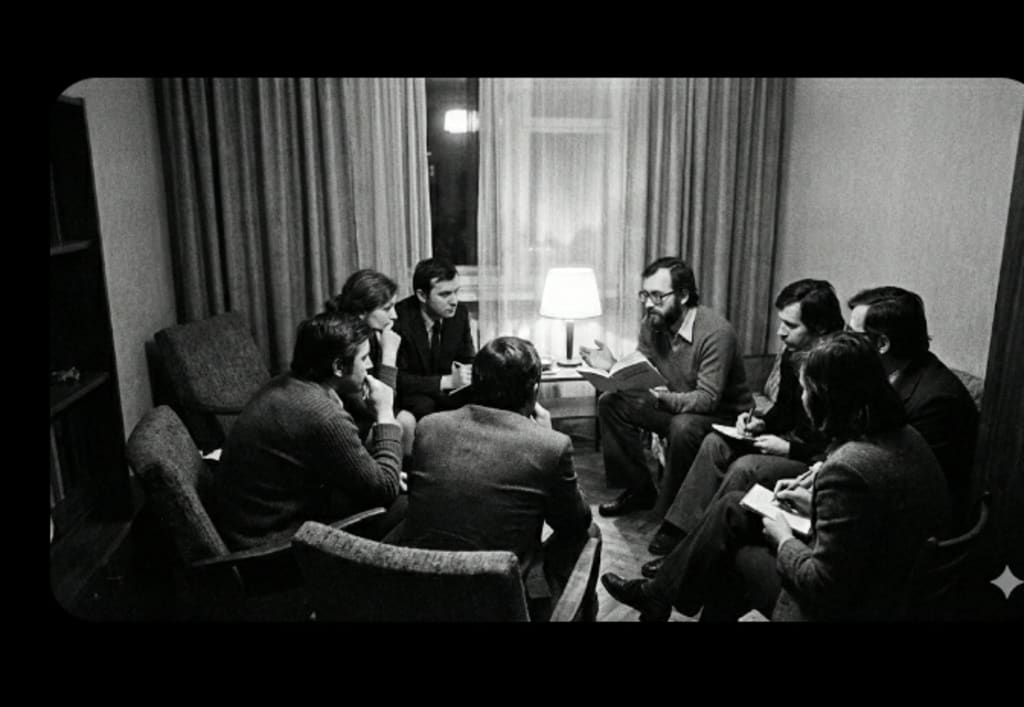

The untold story of the "Flying University" in Communist Poland, where Zofia Romaszewska and others risked prison to teach forbidden history in secret apartments.

Introduction: The Knock at the Door

In 1977, in Warsaw, a knock at the door didn't mean a neighbor was visiting. It didn't mean the postman was there.

It meant your life was about to be dismantled.

Inside a cramped apartment on a Tuesday night, thirty people froze. They were sitting on the floor, on the windowsill, on the arms of a worn-out sofa. The air was thick with cigarette smoke and the smell of damp coats.

Standing by the bookshelf was a professor. In his hand was a book—George Orwell’s 1984, or perhaps a historical account of the Soviet invasion of 1939. Both were banned. Both were illegal to own.

If the person knocking was the Milicja (Police) or the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (Security Service), everyone in that room faced expulsion from university, loss of employment, beatings, or prison.

The professor signaled for silence. He hid the book under a cushion. Someone opened the door a crack.

It was just a late student, breathless, shaking snow off his boots.

The room exhaled. The lock clicked shut. The professor pulled the book back out.

"As we were saying," he whispered, "let us discuss what they are trying to make you forget."

This was the Flying University (Uniwersytet Latający). It had no campus. It had no tuition. It had no official existence.

But for a few years in the gray, suffocating grip of Communist Poland, it was the only place where the truth was allowed to breathe.

Part I: The Gray Cage

To understand why a librarian would risk prison to organize a lecture, you have to understand the grayness of the Polish People's Republic.

It wasn't a war zone with tanks on the street every day. It was a prison of the mind.

The Soviet-backed government controlled everything. They controlled the price of bread. They controlled where you lived. But mostly, they controlled the past.

History books were rewritten.

* The Katyn Massacre (where Soviets executed 22,000 Polish officers)? erased. The books said the Germans did it.

* The Soviet invasion of 1939? erased. The books said the Soviets came to "liberate."

* Sociology? Banned as a "bourgeois pseudo-science."

* Western Literature? Censored.

The regime understood something very dangerous: If you control the vocabulary, you control the thought.

By the mid-1970s, a generation of students was growing up lobotomized. They were being fed a diet of lies so pervasive that reality itself felt slippery.

But there were people who remembered.

Librarians. Historians. Writers.

They knew that a society that forgets its own history is a society that has already surrendered.

Part II: The Woman in the Center

One of the key figures in this underground web was Zofia Romaszewska.

She wasn't a soldier. She was a petite woman, a physicist by training, and a fierce activist. Together with her husband Zbigniew, she operated in the heart of the Workers' Defense Committee (KOR).

Zofia understood logistics. A revolution needs thinkers, yes, but it also needs someone to organize the chairs.

The idea of the "Flying University" was resurrected from the 19th century (when Poles organized secret education under Russian partition). But this time, the enemy wasn't a foreign Tsar; it was their own government.

The structure was simple and chaotic:

* The Professors: Leading academics who had been fired or blacklisted by the state.

* The Venues: Private apartments. People offered their living rooms, knowing that if they were caught, the police could confiscate their furniture, their books, or even the apartment itself.

* The Students: A mix of university kids, factory workers, and curious citizens.

Zofia and the organizers acted as the nervous system. They had to coordinate locations that changed every week—hence the name "Flying."

If you stayed in one place too long, the police would find you.

Part III: Education as Combat

A typical session looked like this:

A courier would whisper an address to a student leader in a university hallway. “Tuesday. 7 PM. Marszałkowska Street. Apartment 4.”

That student would tell three others. No flyers. No phone calls (phones were tapped).

At 7 PM, the apartment would fill up.

The professor would stand in front of a bookshelf. There were no slides. No microphones. Just a voice.

They talked about the things that were forbidden.

They analyzed the economic lies of the Five-Year Plans.

They read poetry that criticized the state.

They discussed human rights.

It sounds romantic now. It wasn't. It was terrifying.

The apartments were hot and airless. People sat for three or four hours on hard floors. The tension was constant. Every siren passing outside made hearts stop.

But the hunger for truth was stronger than the fear.

Students later recalled that these lectures felt like "drinking water after walking in a desert."

For the first time in their lives, nobody was lying to them.

Part IV: The "Unknown Perpetrators"

The regime didn't ignore this. But they couldn't just arrest everyone. Arresting famous professors would create martyrs and international scandals.

So, the government used a dirtier tactic: "Unknown Perpetrators."

These were thugs. Gangs of muscular men, often recruited from judo clubs or criminal prisons, paid by the Secret Police.

They would burst into the apartments during a lecture.

They didn't carry badges. They carried brass knuckles and batons.

They would smash the furniture. They would throw tear gas grenades into the crowded living rooms. They would beat the students and the professors.

In one famous incident, the "Flying Commandos" (as the thugs were called) stormed an apartment where Jacek Kuroń, a legendary dissident, was lecturing. They beat him severely. They beat his son.

The police waited outside. When the victims stumbled out, bleeding, the police shrugged. "Just a private dispute," they said. "Nothing we can do."

This is where Zofia Romaszewska’s work became vital.

She ran the Bureau of Intervention.

When a student was beaten, Zofia was there. She recorded the names. She recorded the injuries. She documented everything.

The regime wanted these beatings to happen in the dark. Zofia made sure they happened in the light. She sent the reports to the West, to Radio Free Europe.

She turned their violence into evidence.

Part V: The Economy of Trust

How do you keep a secret involving thousands of people?

You don't.

The police knew. They had spies everywhere.

But the Flying University survived because of social solidarity.

If a professor was fired for teaching, the underground network raised money to pay his rent.

If a student was expelled, other professors fought to get them reinstated.

It was an ecosystem of trust.

In a totalitarian state, the ultimate goal of the government is to isolate you. They want you to believe that your neighbor is a spy. They want you to be afraid to speak to your brother.

The Flying University broke that isolation.

By sitting together on a floor, listening to a lecture, strangers became allies.

They realized: I am not crazy. The world is crazy. And I am not alone.

That realization is more dangerous to a dictatorship than a bomb.

Part VI: The Slow Burn of Victory

The Flying University didn't overthrow the government. Not directly.

There was no "graduation day" where they marched on the parliament.

It was a slow burn.

The students who sat on those floors in 1977 became the leaders of the Solidarity movement in 1980.

They became the journalists of the underground press.

They became the lawyers who defended political prisoners.

When the massive strikes began in the Gdańsk Shipyard in 1980, the workers weren't just asking for better wages. They were asking for truth.

They demanded the end of censorship. They demanded the truth about history.

Why? Because the Flying University had taught a generation that bread is not enough. You need dignity. And dignity requires truth.

Zofia Romaszewska and her husband continued their work. During Martial Law in 1981, when tanks rolled into the streets and Solidarity was crushed, they went into hiding. They ran Radio Solidarity, broadcasting pirate radio signals from rooftops to keep hope alive.

They were eventually arrested. They went to prison.

But the seeds were already planted.

Part VII: The Lesson of the Librarian

Communism in Poland fell in 1989.

It fell because the economy collapsed, yes. But it also fell because the government lost the war for the human mind.

They had the tanks, the police, the courts, and the prisons.

But the Flying University had the books.

Zofia Romaszewska is an old woman now. She is a dame of the Order of the White Eagle, Poland's highest honor.

But her story is not about medals.

It is a story about the fragility of freedom.

We live in an age where information is everywhere. We drown in it. We take it for granted.

The story of the Flying University reminds us that knowledge is not a luxury. It is a weapon.

In 1977, a librarian, a professor, and a student proved that you don't need an army to fight a dictatorship.

You just need a room, a locked door, and the courage to whisper the truth.

Conclusion: The Quiet Resistance

This story doesn't have a cinematic explosion.

There is no scene where Zofia Romaszewska defeats a tank.

It ends quietly. It ends with a student walking home in the dark, cold Warsaw night, clutching a handwritten copy of an essay inside his coat.

He is scared. He is cold. But his mind is on fire.

He knows something he didn't know yesterday.

And because he knows it, the regime is a little bit weaker.

That is how the world changes.

Not with a bang, but with a book.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.