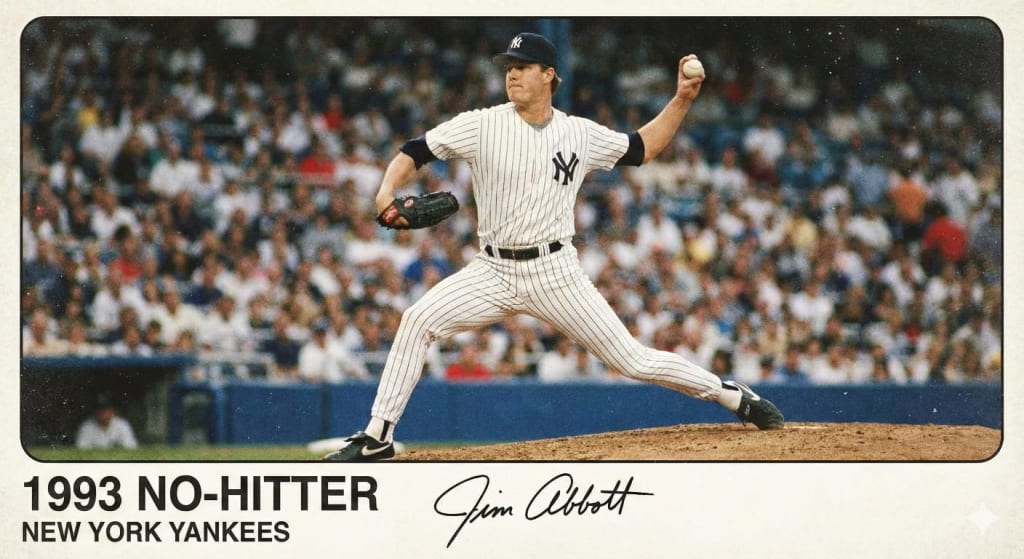

The Phantom Glove: Jim Abbott and the Art of the Impossible

In a game defined by two hands—throw and catch—Jim Abbott only had one. But on a Saturday in the Bronx in 1993, he didn't just play the game. He broke it

The incredible true story of Jim Abbott, the one-handed pitcher who defied physics and skeptics to throw a no-hitter for the New York Yankees, proving that adaptation is the highest form of skill.

Introduction: The Geometry of the Impossible

Baseball is a game of symmetry. It is a game of pairs. Two feet in the batter's box. Two eyes on the ball. And, most critically, two hands to play the field.

The mechanics of being a pitcher are brutal but simple: You hold the ball in one hand and the glove in the other. You throw the ball. If the ball is hit back to you, you use the glove hand to catch it.

In 1967, James Anthony Abbott was born in Flint, Michigan, without a right hand.

He didn't have a prosthetic that worked well. He didn't have a surgery that could fix it. He just had a wrist that ended too soon.

According to the unwritten laws of physics and sports, Jim Abbott should not have been a baseball player. He should have been a fan. He should have sat in the stands.

But Jim Abbott had a problem with the word "should."

He didn't just want to play. He wanted to pitch. And to pitch, he had to invent a magic trick that he would perform thousands of times, often so fast that the human eye couldn't track it.

Part I: The Abbott Switch

Growing up, Jim tried the prosthetics. They were heavy, ugly hooks that made him feel like Captain Hook. They made him stare at the floor in shame.

He hated them. He threw them in the closet.

He wanted to play catch with his dad. But how do you play catch with one hand? If you wear the glove, you can't throw. If you hold the ball, you can't catch.

Jim and his father invented a move out of necessity. It would later become known simply as "The Abbott Switch."

It went like this:

* Jim rested his glove on the end of his right arm (the stump).

* He held the ball in his left hand.

* He threw the pitch.

* The Switch: In the split second after the ball left his hand—while the ball was traveling 90 miles per hour toward the plate—Jim would slide his left hand into the glove.

* He would catch the return throw or a batted ball.

* The Reverse: He would then squeeze the glove against his chest, pull his hand out with the ball, and be ready to throw again.

Read that again.

He had to do this while a professional athlete was hitting a projectile back at him at over 100 miles per hour.

If he fumbled the switch, the ball would hit him in the face. If he was too slow, he would miss the play.

He practiced against a brick wall for hours. Thump. Switch. Catch. Switch. Throw.

His neighbors heard the rhythm of it all night long. It was the sound of a boy rewriting the rules of anatomy.

Part II: The Bunt Test

By the time Jim reached the University of Michigan, he was a sensation. He wasn't a "charity case." He was throwing heat.

But baseball is a cruel game. It seeks out weakness and exploits it without mercy.

Scouts and opposing coaches saw Jim and thought: Bunt.

A bunt is a soft tap of the ball, forcing the pitcher to run forward, field it, and throw to first base quickly. It requires immense dexterity.

"Bunt on him," the coaches screamed. "Make the one-handed kid field his position."

They tried. Oh, how they tried.

But they discovered something frustrating. Jim Abbott wasn't just fast at the switch. He was faster than the two-handed pitchers.

He had practiced the transition so many times that it was fluid, like water. He would deliver the pitch, and by the time he followed through, the glove was already on his hand. He pounced on bunts like a cat.

He shut them down. He won the Golden Spikes Award (the Heisman Trophy of baseball). He led Team USA to a Gold Medal in the 1988 Olympics.

He was drafted by the California Angels. He skipped the minor leagues entirely—a feat almost unheard of.

He was in the Big Show.

Part III: The Bronx Zoo

In 1993, Jim Abbott was traded to the New York Yankees.

If you know baseball, you know that New York is not a place for sentimental stories. The fans don't care if you have one hand, three hands, or tentacles. If you win, they cheer. If you lose, they boo you out of the building.

The 1993 season was a nightmare for Jim.

The pressure was eating him alive. He was pressing. His ERA (Earned Run Average) ballooned. He was giving up home runs.

The whispers started.

“Maybe the league has figured him out.”

“Maybe the gimmick is over.”

“He’s a nice story, but he can’t pitch here.”

Jim wasn't reading the papers, but he felt the stares. He felt the weight of being "The One-Handed Pitcher." He didn't want to be a sideshow. He wanted to be an ace.

By September, he was exhausted. His confidence was shattered.

On Saturday, September 4th, 1993, he walked to the mound at Yankee Stadium to face the Cleveland Indians.

Cleveland had one of the scariest lineups in baseball. Kenny Lofton (speed). Manny Ramirez (power). Albert Belle (rage and power). Jim Thome.

Jim looked at his catcher, Matt Nokes. He took a deep breath.

"Just get through the first inning," he told himself.

Part IV: The Imperfect Perfection

A "No-Hitter" is one of the rarest feats in sports. It means a pitcher throws a complete game (9 innings, 27 outs) without allowing a single hit.

Most pitchers go their entire careers without sniffing one.

That Saturday, Jim didn't have his "good stuff." His fastball wasn't spotting perfectly. He walked the first batter he faced.

The crowd groaned. Here we go again.

But then, something clicked.

Jim started to rely on his "slider"—a breaking ball that moves sharply away from the batter.

In the first inning, he got a double play.

In the second, he got Manny Ramirez to fly out.

He wasn't blowing them away. He was outthinking them.

But the real challenge wasn't the pitching. It was the fielding.

In the early innings, a hard ground ball was smashed back up the middle.

A "comebacker."

This is the nightmare scenario. A ball traveling 105 mph aimed at your shins.

Jim threw the pitch. Switch.

The ball cracked off the bat.

Jim’s glove snapped down. Thwack.

He caught it. He squeezed it to his chest, pulled the ball out, and threw the runner out at first.

The crowd cheered. But it was a nervous cheer.

Part V: The Silence of the Seventh

By the 7th inning, the scoreboard showed a string of zeros for Cleveland.

Runs: 0 Hits: 0 Errors: 0

In baseball superstition, you never say the words "No-Hitter" while it's happening. You don't look at the pitcher. You don't talk to him. You let him sit in his zone.

Jim sat in the dugout, staring at the floor.

His heart was hammering. He knew. Everyone knew.

The pressure in Yankee Stadium was physical. 27,000 people were holding their breath.

But Jim was fighting a battle no other pitcher had to fight.

Every pitch required the switch.

Pitch. Switch. Field. Switch.

Pitch. Switch. Field. Switch.

His left hand was sweating inside the glove. His coordination had to be perfect. If he dropped the glove once, the no-hitter was gone.

Albert Belle, the most feared hitter in the league, came up to the plate. He smashed a ball deep to center field.

Jim held his breath.

Bernie Williams, the center fielder, drifted back. Back. Back.

He caught it at the wall.

The crowd erupted. Jim let out a breath he felt like he’d been holding since 1967.

Part VI: The Ninth Inning

Top of the 9th. Three outs to go.

The stadium was on its feet. The sound was deafening.

Jim Abbott, the man who was told he should get a desk job, the man who was told he was a liability in the field, stood on the mound.

He got the first out.

He got the second out.

One man left. Carlos Baerga. A switch-hitter who didn't strike out often.

Jim looked at Matt Nokes. Nokes signaled: Fastball.

Jim wound up. He kicked his leg high. He threw.

Baerga swung.

Crack.

It was a ground ball to the shortstop, Randy Velarde.

But it wasn't an easy hop. It was a slow roller. Velarde had to charge it.

Jim ran to cover first base, just in case.

Velarde scooped the ball. He threw it across the diamond.

The first baseman caught it.

OUT.

Part VII: The Eruption

Jim Abbott threw his left arm into the air.

He didn't just smile. He roared.

Matt Nokes ran out and tackled him. The entire team piled on top of him.

The crowd at Yankee Stadium didn't just cheer. They wept.

They weren't crying because they felt sorry for him. They were crying because they had just witnessed the absolute destruction of the word "impossible."

Jim Abbott had thrown a no-hitter.

He had faced 27 outs. He had switched his glove roughly 100 times. He had fielded his position. And he had dominated the best hitters in the world.

Later, in the locker room, reporters swarmed him. They wanted the inspirational quote. They wanted him to talk about being disabled.

Jim wiped the champagne from his eyes and said something profound:

"I’ve never been so happy to be just a pitcher."

In that moment, he wasn't "Jim the one-handed guy." He was "Jim the Ace."

Part VIII: The Real Legacy

Jim Abbott played ten seasons in the Major Leagues. He retired with 87 wins.

But his legacy isn't in the stats.

Jim Abbott changed the way the world looked at disability.

He proved that adaptation is not compromise.

When people looked at Jim, they saw what was missing. They saw the empty right sleeve.

When Jim looked at himself, he saw a left arm that could throw a baseball through a brick wall.

He didn't ask the league to let him pitch from a closer distance. He didn't ask for a designated fielder. He played by the exact same rules as everyone else.

He realized that the world doesn't care about your circumstances; it cares about your results.

Conclusion: The Excuse Killer

We all have excuses.

I’m too old.

I’m too short.

I don’t have the connections.

I wasn't born with the right gifts.

Jim Abbott stands on the mound of history and quietly destroys every single one of those excuses.

He teaches us that we are not defined by what we lack. We are defined by what we do with what we have.

If a man can throw a no-hitter in the Major Leagues with one hand, surely you can start that business. Surely you can write that book. Surely you can make that sales call.

Jim Abbott didn't overcome his disability. He simply refused to let it be the most interesting thing about him.

He mastered the "Abbott Switch"—not just the physical move of the glove, but the mental switch of the soul.

The switch from "Why me?" to "Watch me."

And on a September afternoon in the Bronx, the whole world watched him. And they didn't see a missing hand. They saw a legend.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.