The Man Who Stopped the Clock: How a Bureaucrat Saved Lives With a Map

In rural Japan, people were dying because ambulances couldn't find them. One man realized the problem wasn't the drivers, or the roads, or the hospitals. It was the map

The true story of Masao Yoshida, a Japanese civil servant who revolutionized emergency response in rural areas by redesigning the addressing system, saving countless lives.

Introduction: The Geography of Death

In the mountains of rural Japan, time works differently. It moves slower. The roads are narrower. The landmarks are centuries old—a stone shrine, a twisted pine tree, a patch of moss.

But in an emergency, time is the enemy.

In the late 1990s, before every phone had GPS, calling an ambulance in a rural Japanese village was a gamble with death. The dispatchers in the city centers didn't know the local roads. The ambulance drivers, often rotated in from other areas, were driving blind.

A panicked call would come in: "My father is collapsing! Please hurry!"

The dispatcher would ask for the address.

And the caller, terrified and confused, would give the only directions they knew:

"We are past the old bridge, near the noodle shop that closed last year, turn left at the big rock that looks like a turtle."

The ambulance driver would take off, siren wailing.

Five minutes would pass. Then ten.

The driver would slow down at an intersection, looking for a "turtle rock" that he couldn't see in the dark. He would stop to ask a local farmer for directions. The farmer would point vaguely up the mountain.

More minutes ticked by.

Inside the house, the father’s breathing would stop.

He wasn't too far away. He wasn't unreachable. He was simply unlocatable. He died not because medicine failed, but because geography did.

This was the silent crisis happening across rural Japan. A crisis of inefficiency that was killing people quietly, one confusing phone call at a time.

Until Masao Yoshida noticed the pattern.

Part I: The Invisible Man in the System

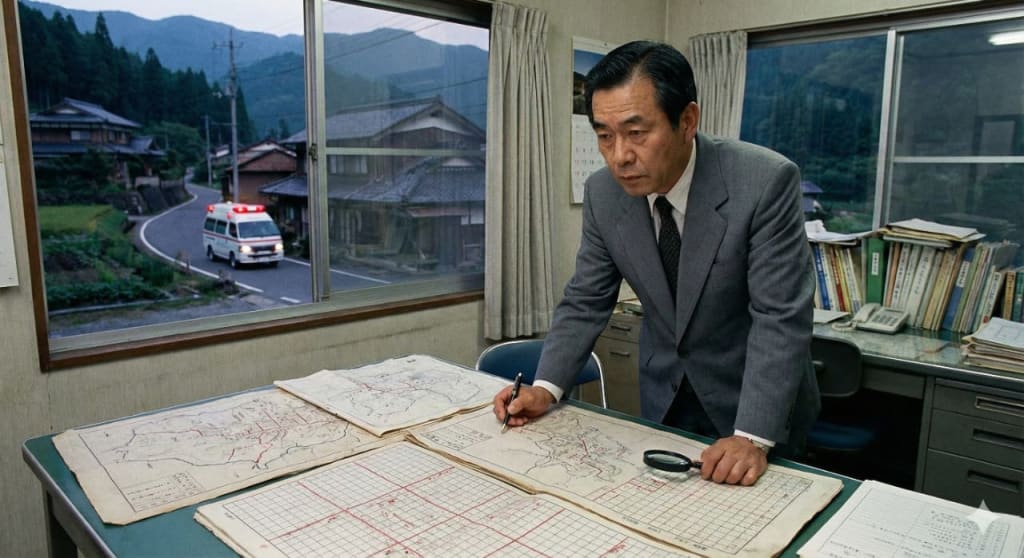

Masao Yoshida was not a hero. He didn't wear a uniform. He didn't run into burning buildings. He was a mid-level civil servant, a bureaucrat in a gray suit working in a fluorescent-lit office. His job was paperwork.

His specific job was reviewing post-emergency reports. He read the debriefs from ambulance crews. Most people would have scanned them and filed them away.

But Yoshida was the kind of man who noticed details.

He began to see a recurring theme in the "Delays" section of the reports.

* “Unable to locate residence due to unclear landmarks.”

* “Spent 12 minutes searching for access road.”

* “Caller provided contradictory directions based on local slang.”

He started tracking the data. He realized that the average response time in rural areas was double that of urban areas. The difference wasn't distance; it was confusion.

The problem wasn't that the ambulances were slow. It was that they were lost.

Japan has a notoriously complex addressing system. In many rural areas, there are no street names. Houses are often numbered not in order along a street, but in the order they were built. House #1 could be next to House #50.

For a mailman who has worked the route for 30 years, this is fine. For an emergency responder driving at 80 kilometers an hour at 2:00 AM, it is a nightmare.

Yoshida realized that the system was designed for locals, not for emergencies. It was designed for a slower world.

He realized: "We are trying to navigate a modern crisis with a medieval map."

Part II: The Resistance of Tradition

Yoshida didn't have the power to change national laws. He couldn't pave new roads or force villages to name their streets. He had no budget.

So, he decided to hack the existing system.

He started in his own prefecture. He proposed a pilot project to create a new, standardized way of referencing locations for emergency services.

He called it the "Grid and Block System."

It was absurdly simple. He took a map of a village. He overlaid a grid. He divided the village into logical blocks based on permanent, unmoving features—rivers, main roads, power lines.

Instead of "turn left at the turtle rock," the new system would translate a location into a coordinate: "Block C, Grid 4, House 12."

It didn't require new street signs. It just required the dispatchers and the drivers to use the same map.

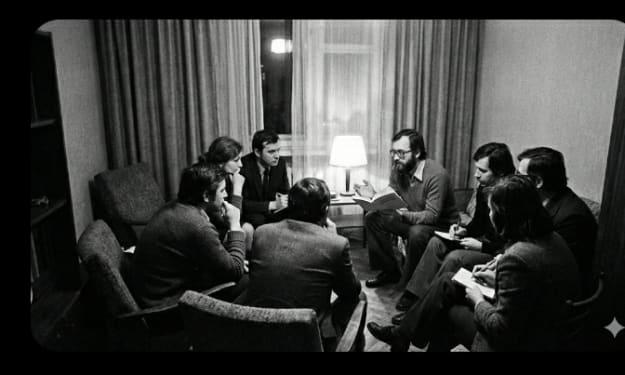

When he presented this idea to the local government chiefs, they laughed at him.

They were old men, steeped in tradition. They liked their village the way it was.

"Why do we need this?" they asked. "Everyone here knows where everyone lives."

Yoshida tried to explain that the ambulance drivers didn't live there.

They told him it was too complicated. They told him the villagers—many of them elderly—would never learn a new system. They told him he was a city bureaucrat trying to impose order on a rural world.

"You cannot turn a mountain village into a chessboard," one elder told him.

Yoshida didn't argue. He didn't get angry. He just went back to his desk and kept refining the maps.

Part III: The Quiet Revolution

He changed tactics. Instead of trying to force the system on the villagers, he focused on the dispatch center.

He spent months working with the dispatchers. He created large, laminated maps with his grid system overlay. He trained them on how to translate the panicked, confused directions of a caller into a grid coordinate.

When a caller said, "I'm near the old temple," the dispatcher would look at the map, find the temple, and see that it was in Block B, Grid 2. They would then tell the driver: "Head to Block B-2. Look for the temple."

It was a translation layer between local knowledge and emergency logic.

He also worked with the ambulance drivers. He gave them the same maps. He taught them how to read the grid. He ran simulations.

The drivers were skeptical at first. But in the simulations, they noticed something: they stopped hesitating at intersections. They stopped looking for "turtle rocks." They just looked at the grid.

They were faster.

Part IV: The Test

The system went live quietly on a Tuesday. There was no press conference. No ribbon cutting. Just new maps on the dispatchers' desks.

The first call came in that afternoon. An elderly woman had fallen down a steep embankment behind her house.

The caller was her neighbor, hysterical.

"She's behind the Sato house! Near the big persimmon tree! Hurry!"

Before Yoshida's system, the dispatcher would have relayed: "Behind Sato house, near persimmon tree." The driver would have spent ten minutes trying to figure out which "Sato house" it was, and which persimmon tree.

But this time, the dispatcher looked at the map. He found the cluster of houses belonging to the Sato family. He saw they were all in Grid D-3.

He radioed the driver:

"Location is Block D, Grid 3. Eastern edge. Look for embankment behind houses."

The ambulance driver looked at his map. He saw D-3. He saw the road leading directly to it. He didn't have to think. He just drove.

They arrived in seven minutes.

The previous average for that area was fifteen.

They found the woman. She was badly injured, hypothermic, but alive. They stabilized her and got her to the hospital.

The doctors said later that if they had arrived ten minutes later, she would have died of exposure.

Part V: The Invisible Success

The pilot program ran for six minutes. The data was undeniable.

Response times in the test areas dropped by an average of 30%. In some particularly confusing areas, they dropped by 50%.

Suddenly, the village elders who had mocked Yoshida were silent. They couldn't argue with the math of survival.

The system began to spread. Neighboring districts adopted it. Then the prefecture. Eventually, elements of Yoshida's logic were integrated into the national emergency response protocols.

And here is the most Japanese part of the story: Masao Yoshida was never promoted. He didn't become famous. He didn't write a book.

He remained a mid-level bureaucrat. He kept reviewing reports. He kept tweaking the maps, making them slightly better, slightly clearer.

He retired quietly a few years later.

Today, if you fall down a mountain in rural Japan, the ambulance will find you. You will likely survive. You will thank the doctors. You will thank the driver. You will thank your lucky stars.

You will never know that you are alive because twenty years ago, a quiet man in a gray suit decided to draw lines on a map.

Conclusion: The Power of the Boring Solution

Why does this story matter?

We live in an age obsessed with disruption. We want revolutionary technology. We want AI, drones, and flying ambulances.

We forget that sometimes, the biggest problems have the most boring solutions.

Masao Yoshida didn't invent a new technology. He invented a new process.

He showed us that systems don't break with a bang; they break with a thousand tiny inefficiencies. They break because we rely on "how it's always been done" instead of looking at "how it actually works."

He proved that you don't need power to change a system. You just need the obsessive attention to detail to see the invisible cracks in the foundation.

He was a bureaucrat. A paper-pusher. A cog in the machine.

But he was the cog that made the machine work.

His legacy isn't a statue. It’s the silence of a telephone that doesn't ring with news of a preventable death.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.