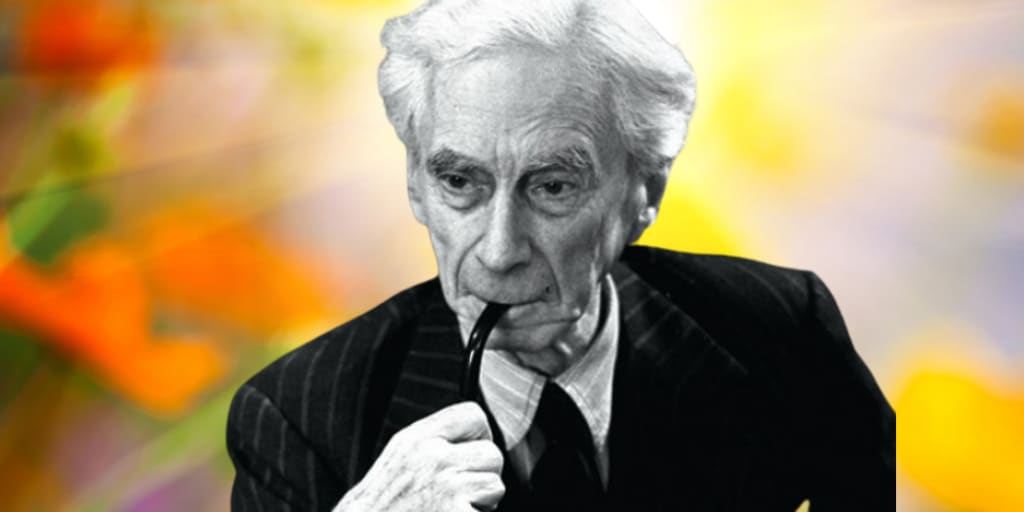

Bertrand Russell on Happiness

A selection of thoughts on happiness and unhappiness from the philosopher, mathematician, and activist.

I was doing some research for a series of articles last year on the nature of happiness, and material from Russell made its way under my nose. No doubt you have heard, and perhaps have read his material before now. However, if on the contrary you have not, a very brief introduction;

Bertrand A.W. Russell (1872–1970) was a British philosopher, logician, essayist and social critic best known in academia for his work in mathematical logic and analytic philosophy. His famous paradox, theory of types and work with Alfred North Whitehead on Principia Mathematica re-energised the study of logic in the twentieth century. In the public mind, he was as famous for his atheism and his activism during WWII and subsequent conflicts, as he was in the realms of philosophy.

On Sources of Unhappiness

“Though the kinds are different, you will find that unhappiness meets you everywhere. Stand in a busy street during working hours, or on a main thoroughfare at a week-end, or at a dance of an evening; empty your mind of your own ego and let the personalities of strangers about you take possession of you one after another. You will find that each of these different crowds has its own trouble”

Engaged in the pursuit of pleasure, it is conducted by all at a uniform pace, Russell says. This was written in 1971 but is no less accurate than it is today. Arguably, it is more so. We are completely absorbed in distraction tactics — anything to avoid seeing ourselves for what we are, really.

Russell speaks of the importance of the creation of wealth, but what use is wealth, he asks, if everyone rich is miserable? The purpose of The Conquest of Happiness, Russell says, was to propose a cure for the ordinary day-to-day unhappiness from which most people in civilised society suffer.

“I believe this unhappiness to be very largely due to mistaken views of the world, mistaken ethics, mistaken habits of life, leading to the destruction of that natural zest and appetite for possible things upon which all happiness, whether of men of animals, ultimately depends.”

From his autobiography, we read that Bertrand Russell contemplated suicide regularly in his teenage years such was his depression at the prospect of living to old age. The only thing that prevented this was his urge to know mathematics. Reflecting on this period in his later years, he reported to love life more and more with each passing year. He suffered just like you and I do, but the force to live and understand the world was stronger for him than the drive for death. I would say that a report on happiness coming from an individual who has been on the brink only to come back, has greater value than that of someone who has not been where he was.

He attributes his recovery from this depressive state to removing his focus from himself. That is, his focus on his deficiencies. He says;

But very largely, it [love of life] is due to a diminishing preoccupation with myself. Like others who had a Puritan education, I had the habit of meditating on my sins, follies, and shortcomings. I seemed to myself — no doubt justly — a miserable specimen. Gradually I learned to be indifferent to myself and my deficiencies.”

“The secret of happiness is very simply this; let your interests be as wide as possible…”

On Curing Unhappiness

Russell goes onto say that the only way to recover from a negative preoccupation with oneself is to become occupied in the world. He recognises external interests can bring discomfort and disappointment, but these kinds of pains do not disrupt, necessarily, the essential quality of life as those that come from self-deprivation and self-flagellation. He says that the road to happiness for those whose self-absorption is too profound to be cured in any other way, can only be achieved through external discipline.

Russell cites many and varied sources of unhappiness, but suggests that the most profound is our preoccupation with distraction through pursuit of hedonic pleasure. Alcohol, drugs, sex, social media, TV programs that heighten our sense of isolation and powerlessness; they are a means to make the unbearable bearable.

As long as we continue to obsess over why we are unhappy, Russell says, we remain self-absorbed and therefore create a vicious circle. If we are to get ourselves outside it, we must find something that absorbs our interests.

“…it must be by genuine interests, not by simulated interests adopted merely as a medicine. What those objective interests are to be that will arise in you when you have overcome the disease of self-absorption must be left the spontaneous workings of your nature na of external circumstances.”

Sounds to me like he’s suggesting that we just follow our curiosity and go with the flow. Instead of doing what is expected of us or what we think we should be doing, we should pursue the interests that arise in us from simply being alive.

Russell finishes The Conquest of Happiness by suggesting that through engagement in naturally occurring interests, we come to feel ourselves part of the stream of life, not a hard and separate thing such as a billiard ball. All unhappiness, he says, depends upon some form of disintegration or lack of integration; a schism within the self, or the self and that of society. The happy person is not a divided subject, nor are they isolated from and at odds with the objective world.

“The secret of happiness is very simply this; let your interests be as wide as possible, and let your reactions to the things and persons that interest you be as far as possible friendly rather than hostile.”

My View Hasn’t Changed

Nothing profound in this book for me, and my view on happiness/unhappiness hasn’t changed. Happiness does not exist at either end of an imaginary spectrum. It comes about, in fact, in the experience of both good and bad. It’s not a denial of terrible conditions, but a willingness to do whatever it takes to get somewhere better.

It’s naïve to look for happiness, for a couple of reasons;

- Looking for it reinforces its absence.

- Whatever we think it is, it is not.

Russell is accurate, I think, in that preoccupation with what we don’t have perpetuates it. If we feel like crap, we’ve got to somehow take ourselves out of the circular pattern and into something else that takes our attention. It’s almost like we have to derail ourselves before we can find a new track. That’s certainly how it seems to have been for me.

Anyway…

There’s a lot of waffle in this book, and an over-use of language unnecessarily. But there’s value in it nonetheless.

About the Creator

Larry G Maguire

I'm a writer and work psychologist in private practice at HumanPerformance.ie. I work with people on workplace well-being, leadership, culture and performance and provide one-to-one sessions, group training and workshops. Subscribe here

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.