The Current Ebola Crisis

As of June 4, 2019, this is considered the second largest Ebola outbreak in history.

Ebola has developed a major threat to mankind in recent years. Although the virus has been present and familiar to science since its discovery in 1976. The risk of a worldwide epidemic has increased greatly due to advances in globalisation. The 2014 to 2016 outbreak in West Africa brought the virus into the global spotlight.

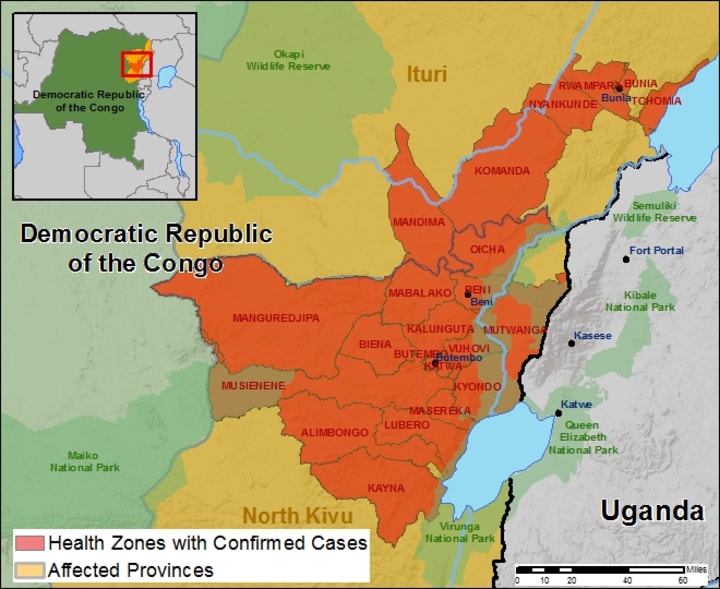

But did you know that there's another outbreak? It began in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) back in 2018, and as of June 4, 2019 it's consider the second largest outbreak in history, behind the 2014 to 2016, which killed more than 11,300 people. Currently, there have been 1,994 confirmed cases, with a death toll of approximately 1,339. Aid agencies working in DRC are set announce that more than 2,000 people have been infected with Ebola since the outbreak was declared.

Scientists have been working on an Ebola vaccine for at least a decade before the 2014 outbreak, and according to data released by the World Health Organization in April 2019, an experimental vaccine is being used to try to contain the current outbreak in DRC, and was proving to be effective. Of more than 90,000 people who were vaccinated, only seventy-one went on to develop Ebola and fifty-six of those people developed symptoms fewer than ten days after being vaccinated. This makes scientists believe that it takes around ten days for an immune protection to develop after being vaccinated. It's also worth noting, that none of the people who had developed Ebola 10 days or more after vaccination died from the virus.

The vaccine, which is begin developed by Merck, is being used in what is known as a ring vaccination. Simply, those who have had close or high-risk contact with known Ebola cases are offered the vaccine. Then contacts of those contacts are offered the vaccine. Finally, those who are also at high-risk of exposure due to jobs—health workers, ambulance drivers, etc.—are also offered to be vaccinated. The thought is to build a wall of protection, cutting off the virus's ability to spread.

Despite an effective vaccine, medical teams and new treatments being tested in the region infection and death tolls continue to rise. Aid workers went from seeing three to five cases a day to a staggering eight to more than twenty cases a day.

Why?

In this particular outbreak, the virus seems to be infecting an unusually high number of children and killing a large percentage of people before they are able to seek or receive treatment. As teams try to track the spread, they are finding brand new cases with no obvious connection to previous patients, sending some health specialists to worry that the end of the epidemic in nowhere in sight.

Photo Source: CDC

Then there was a delay, or rather an inability in vaccinating those in the hot spots, during a spike in cases. This was due to many parts in the Katwa and Butembo areas being too dangerous for vaccination teams to operate. And, as proven time and again with infections, any type of delay makes the treatment more dangerous and gives it more chances to spread and kill. Rebel attacks, violence, political conflict and a deep mistrust of outsiders, make it all the more dangerous for aid workers to treat patients and hesitant for people to seek treatment.

No one is sure if this outbreak will reach the scale of West Africa or not, but the current outbreak is enormous in comparison to any other outbreak in Ebola history and the frightening aspect is how it continues to spread and the amount of infections keep going up. It's amazing that this has yet to spread more geographically, but it's only a matter of time until it begins spreading to neighbouring Rwanda or Uganda. With all the violence taking place in the hot and surrounding areas, it's only a matter of time until a single person or family flee to another country for their own safety, unknowingly bringing the Ebola virus with them. Only time will tell if this will happen; but the notion that this epidemic will be brought under control in the near future is bleak.

Ebola Facts:

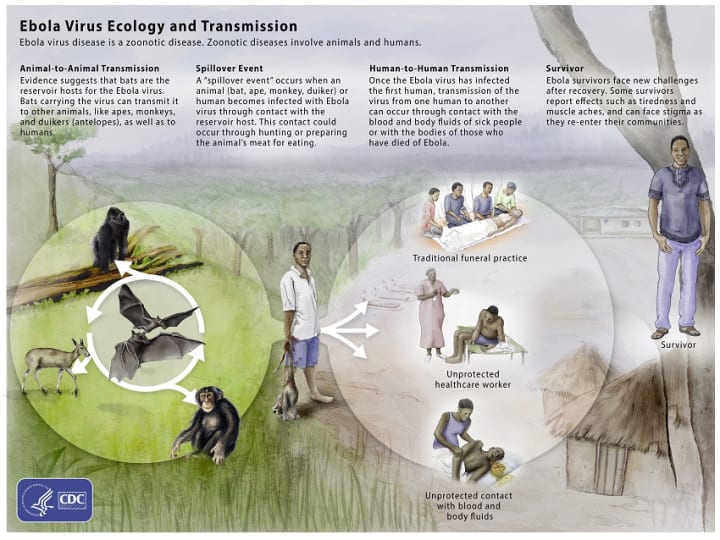

Photo Source: CDC

- Ebola virus disease (EVD) also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF) is a rare but often fatal disease.

- It can be transmitted to people from wild animals and direct human-to-human contact. This includes bodily fluids such as blood, feces, vomit, breast milk or semen. People remain infectious as long as their blood contains the Ebola virus.

- Ebola first discovered in 1976 in two simultaneous outbreaks. One in Nzara (a town located in South Sudan) and the other in Yambuku (Democratic Republic of the Congo), a village near the Ebola river, from which the disease takes its name.

- The 2014 to 2016 outbreak in West Africa is currently the largest Ebola outbreak since the disease was discovered. The current 2018 to 2019 is highly complex and the second largest outbreak.

- Ebola is part of the Filoviridae family that includes Cuevavirus, Dianlovirus, Marbugvirus and Ebolavirus.

- Within Ebolavirus are Bundibugyo, Sudan, Tai Forest, Bombali, Reston, (which is not thought to cause disease in humans, but has caused disease in other primates) and Zaire (the most dangerous and was the virus that causes the current outbreak in DRC and the 2014 to 2016 West African outbreak).

- Symptoms of Ebola include, fever, severe headache, rash, muscle pain, sore throat, Fatigue, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, weakness, unexplained bleeding or bruising.

- Symptoms can mimic commons illnesses such the flu or malaria.

- Symptoms may appear anywhere from two to twenty one days after contact with the virus, with an average of eight to ten days.

- Since it can be difficult to tell if a person has Ebola from the symptoms alone, doctors may run tests to rule our other diseases like cholera or malaria. Blood tests and tissues samples can help diagnose Ebola. If positive, the person will be isolated from the public immediately to try and prevent the spread. Public health workers will also conduct an investigation that includes tracing all possible expose contacts.

- Supportive care, such as rehydration with oral or IV fluids, and treatments for specific symptoms can improve survival. While there is currently no proven treatment available for Ebola, a range of potential treatments including blood products, immune and drug therapies are being evaluated.

- The current 2018 to 2019 outbreak in DRC, is the first ever multi-drug randomised control trial. It is being conducted to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of drugs used in the treatment of Ebola.

- If in an area where Ebola is present, don't eat or handle raw or undercooked meat or any bushmeat.

- Lab workers, ambulance drivers, doctors and nurses are at high risk of contracting the Ebola virus. Those working with patients and samples related to the virus should be trained. They should avoid contact with infected persons without the use of recommended protective equipment. Equipment includes masks, gloves, gowns and goggles.

- Whether you've come into contact with Ebola or not, its always a good idea to never touch your eyes, nose or mouth until your hands are clean. Wash your hands often. If soap and water are not available, using a hand sanitiser that contains at least 60 percent alcohol.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.