Severe Perspective | Pathophysiology of Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock

Recently discovered

Although the classic pathophysiological pathway of cardiogenic shock (ie, reduced organ perfusion due to insufficient cardiac output and peripheral vasoconstriction) has been around for a long time, the role of macroscopic and microscopic hemodynamics in the severity of the disease and its prognosis It has only been widely studied in recent years. In addition, in order to complete the complex picture of the pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock, research on cytokine cascade, inflammation and proteomics analysis has also recently been put on the agenda.

to sum up

Understanding the pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock is very important for its optimal treatment.

Key points

• Cardiogenic shock is characterized by peripheral vasoconstriction and severe end-organ damage caused by insufficient stroke volume and oxygen delivery.

• A significant decrease in myocardial contractility can cause cardiogenic shock syndrome.

• Systemic inflammation activation and decreased vascular tone change the classic hemodynamic characteristics of the previous decreased cardiac output and peripheral vasoconstriction.

• On the basis of investigating the case of cardiogenic shock and understanding its pathophysiology is essential for how to deal with the syndrome correctly.

Introduction

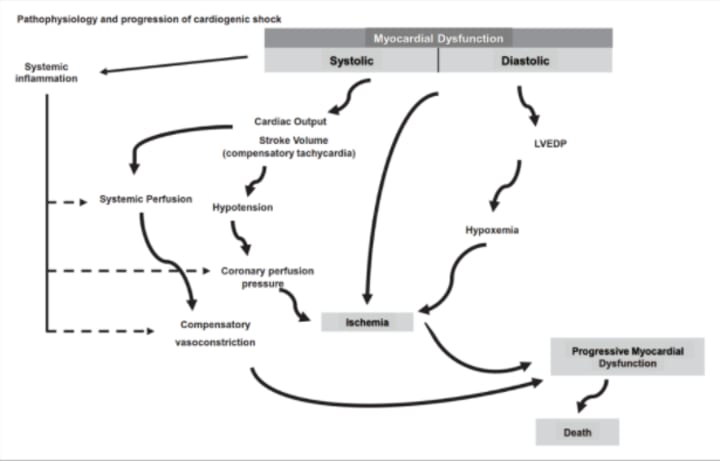

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is characterized by peripheral vasoconstriction and severe end-organ damage caused by insufficient cardiac output (CO) and oxygen delivery (DO2). In general, cardiogenic shock involves a significant decrease in myocardial contractility, and a significant decrease in myocardial contractility can gradually and potentially lead to a decrease in cardiac output, a decrease in blood pressure, and further coronary ischemia, all of which may lead to Further reduction in myocardial contractility and multiple organ failure. This closed loop may end in death.

To determine the underlying cause, specific drugs or mechanical treatments can be initiated after hemodynamic recovery and stabilization. The current record shows that up to 81% of patients with cardiogenic shock have the underlying acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Therefore, for patients with risk factors for coronary heart disease, acute coronary syndrome should be the primary examination object for the initial diagnosis, and the electrocardiogram within 10 minutes after the onset of symptoms should be included in the examination.

It is well known that cardiogenic shock can cause acute and subacute disorders of the entire circulatory system and the surrounding vascular system. Hypoperfusion of limbs and vital organs is also common. If the trigger event is insufficient stroke volume (SV), peripheral vasoconstriction can maintain tissue perfusion pressure to improve coronary and peripheral perfusion, and it also represents an increase in afterload. This situation is complicated by changes in tissue perfusion and systemic inflammation triggered by acute heart injury, which in turn will complicate pathological vasodilation. Tachycardia is the most common type of supraventricular tachycardia, and tachycardia is generally considered to be an important compensatory mechanism for stroke volume decline.

Primary heart problems

The classic pathological process is myocardial tissue damage after severe acute myocardial infarction (AMI), leading to severe left ventricular insufficiency. Although the etiology may be different, the pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock involves many different but superimposing factors: initial cardiac damage, reduced cardiac output, and changes in central hemodynamics [including left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV) Changes in the interaction between pressure and volume when filling pressure increases], microcirculation instability, systemic inflammation, and organ dysfunction. These events can be considered as transient cardiogenic shock stages, and depending on the severity of the initial heart injury and/or the early implementation of treatment, each of these events may be delayed. In addition, in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), predisposing factors such as arrhythmia or respiratory tract infection can cause acute deterioration of cardiac compensatory function and evolve into cardiogenic shock. In patients with no underlying cardiovascular disease, if cardiogenic shock occurs, the results are often worse.

Due to the sharp drop in the left ventricular contractility, the cardiac output decreases, resulting in a sharp drop in blood pressure, followed by an increase in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. Hypotension causes compensatory vasoconstriction, which functionally transfers blood volume to the circulatory pool, leading to increased cardiac filling pressure, thereby changing the ventricular-arterial coupling (VAC). The constriction of blood vessels throughout the body ultimately leads to an increase in afterload and a decrease in heart function. Eventually, the oxygen delivery (DO2) of peripheral tissues and the heart itself will be severely reduced.

The changes in tissue microcirculation are also related to the patient’s 30-day mortality rate and the temporal changes in the sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, which can be improved by mechanical circulatory support (MCS). A severe reduction in cardiac output (CPO = CO×BP) is a sign of extreme left ventricular dysfunction, and cardiac output below 0.53W is a strong indicator of adverse results.

The role of the right ventricle

Since the right ventricle is a "displacement pump" rather than a "pressure pump", the right ventricle cannot effectively withstand the sharp increase in afterload. Right ventricular dysfunction caused by primary systolic dysfunction or secondary preload/afterload imbalance may be the main cause of cardiogenic shock (such as acute pulmonary embolism, simple primary tricuspid regurgitation and right Ventricular cardiomyopathy). Similarly, when right ventricular dysfunction and left ventricular abnormalities (right ventricular infarction related to lower wall myocardial infarction, severe pulmonary hypertension) can also lead to cardiogenic shock. In severe right ventricular dysfunction, cardiogenic shock may be accompanied or not accompanied by pulmonary hypertension.

The effects of right ventricular failure are mainly due to "venous congestion." Due to the low venous vascular resistance, the driving pressure of the venous return to the right ventricle is also low (about 5mmHg), but the right ventricle congestion must be maintained by a proportional increase in venous pressure. In order to maintain the venous return in patients with cardiogenic shock, the pressure of the right atrium suddenly increases to 15 mmHg. At this time, the venous pressure of the tissue needs to be close to 20 mmHg. By reducing the perfusion pressure gradient (the difference between the arterial pressure of the system and the venous pressure of the organ), this back pressure in the organ can significantly impair its perfusion. Therefore, insufficient forward blood flow is the cause of insufficient end-organ perfusion and increased venous pressure when the right ventricle is damaged. Eventually, because right ventricular failure causes the right ventricle to expand, the ventricular septum moves to the left ventricle, impairing the filling of the left ventricle, and causing subendocardial ischemia. If this change persists, it can further aggravate systemic hypoperfusion. When the pulmonary artery pulsatility index [(pulmonary artery systolic pressure-pulmonary artery diastolic pressure)/right atrial pressure] decreases (pulmonary artery pulsatility index <0.9), it indicates a significant loss of right ventricular function.

Changes in microcirculation during cardiogenic shock

Patients with cardiogenic shock have early microcirculation dysfunction. It is associated with the development of multiple organ failure and indicates a poor prognosis for patients with acute myocardial infarction combined with cardiogenic shock. Systemic hypoperfusion leads to systemic inflammation, resulting in a large amount of nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation and a significant reduction in systemic vascular resistance. Other systemic inflammatory mediators that induce vasodilation include interleukin and tumor necrosis factor-α. Regardless of the mechanism, these inflammatory mediators can counteract certain aspects of the positive inotropic effects of neurohormones, resulting in reduced systemic vascular resistance and impairing the potential for venous dilatation, both of which can lower blood pressure and cause cardiogenic shock. The vicious circle continues to develop.

Since the microcirculation network depends on blood flow, the decrease in cardiac output and the increase in vascular tone may reduce the reactivity of capillaries, leading to hypoxia.

However, even under extreme hypoxia, the activity and function of mitochondria can be maintained for several hours. Animal models show that mitochondrial function is initially upregulated to meet metabolic demands. Changes in the biology of NO stored in red blood cells may cause vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation, and insufficient oxygen supply; blood transfusion may also cause inflammation.

On the second day after the onset of cardiogenic shock, clinically 20-40% of patients with cardiogenic shock will have obvious inflammation, which can lead to the initial reduction of systemic vascular resistance (SVR). Studies have shown that after the onset of cardiogenic shock, increased levels of cytokines (interleukin-1, 6, 7, 8, 10) can be observed immediately and are associated with early mortality. Local causes that promote vasodilatation include NO-mediated pathological vasodilation, blood glucose disorders, and a sudden increase in advanced glycation end products-these factors are all related to the increased risk of death. Unfortunately, for cardiogenic shock, there is no research to prove that anti-cytokine therapy or anti-NO therapy is successful.

A subgroup analysis of the BUCKONG-SHOCK study emphasized the important and independent correlation between microcirculation perfusion parameters and 30-day all-cause mortality and the comprehensive clinical outcome of renal replacement therapy, especially in microcirculation and macrocirculation perfusion parameters Among patients with inconsistent hemodynamics. Although research on cardiogenic shock microcirculation is tempting, its response to therapeutic stimuli is often unrelated to structural consequences; interventions aimed at normalizing cardiogenic shock microcirculation are currently inconclusive.

Acute onset of chronic heart failure

5%~12% of patients with acute coronary syndrome have cardiogenic shock. Mechanical complications (including rupture of the papillary muscle, ventricular septal defect, or free wall rupture of the heart) are traditionally considered late complications, but they usually occur within 24 hours of hospitalization. For such a diagnosis, a high degree of vigilance and rapid echocardiography is required.

Chronic heart failure may be in an acute decompensated state, which can account for 30% of cardiogenic shock cases. These patients have experienced a decrease in the stability of their disease or poor adherence to guideline-based treatments, which can cause their chronic disease to worsen drastically. The hemodynamic status and sensitivity to neurohormones are often quite different. Therefore, the treatment of chronic heart failure patients with cardiogenic shock may be quite different from the treatment of non-chronic heart failure. Vasoconstrictors, such as angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and norepinephrine, often need to be significantly upregulated in the treatment of patients with heart failure.

Other factors that cause cardiogenic shock

Other conditions may cause instability and worsening of cardiogenic shock (Table 1). If not detected or insufficiently monitored, advanced heart valve disease and artificial heart valve dysfunction can also manifest as cardiogenic shock. Although with the improvement of echocardiography technology and monitoring, this possibility becomes smaller and smaller. Paradoxically, in acute myocarditis, the most severely ill patients have the greatest chance of recovery, especially younger patients. The rapid recognition of clinical symptoms and the rapid adoption of active hemodynamic support may be critical to the survival of these patients.

Stress cardiomyopathy or Takotsubo syndrome is becoming more and more familiar. It is related to cardiogenic shock and may also require mechanical circulatory support, although sometimes it will only show mild cardiovascular damage. In this syndrome, left ventricular dysfunction is usually transient.

Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism may also lead to circulatory failure. Heart diseases associated with pregnancy, including perinatal cardiomyopathy and acute coronary dissection can also be manifested as cardiogenic shock. Many other causes of cardiogenic shock have been discovered, but these causes are usually relatively rare (less than 1%).

2-6% of patients after cardiac surgery have cardiogenic shock. The reason may be insufficient cardiac output (causing myocardial hibernation, myocardial stunning, or insufficient myocardial protection), systemic vasodilation, or any of the above conditions.

Approximately 20-30% of patients with cardiogenic shock are co-infected.

Multiple organ dysfunction in sepsis or septic shock is the result of the combined effect of macro hemodynamic changes and microcirculation dysfunction, and indicates a poor prognosis for patients. Myocardial depression is a recognized factor leading to hemodynamic changes in patients with sepsis, and it is also a characteristic of septic cardiomyopathy. Some myocardial inhibitory factors have been identified, including inflammation and pathogenic factors. However, a key pathophysiological factor seems to be endothelial dysfunction, which is caused by inflammation-related increase in endothelial permeability and leads to cardiomyocyte edema and dysfunction. In addition, in addition, mechanisms related to changes in NO metabolism, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, autonomic dysfunction, and abnormal calcium transport are thought to be involved.

Damage to the microcirculation of the intestinal barrier leads to increased bacterial translocation, and the intestine is often one of the first organs affected by shock. The lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) produced by gram-negative bacteria enters the blood, leading to the development of cytokines and inflammation, thereby accelerating hemodynamic disorders, leading to multiple organ failure. In addition, sedatives that inhibit the heart (such as propofol), antiarrhythmic drugs, β-blockers, improper use of diuretics, and excessive volume load during right ventricular shock may all cause cardiogenic Iatrogenic factors of shock cardiovascular system dysfunction.

Interaction between the heart and blood circulation

Bedside pressure-volume (P-V) measurement is increasingly used in clinical practice to better explain the pathophysiological mechanism of cardiogenic shock and customize its treatment plan.

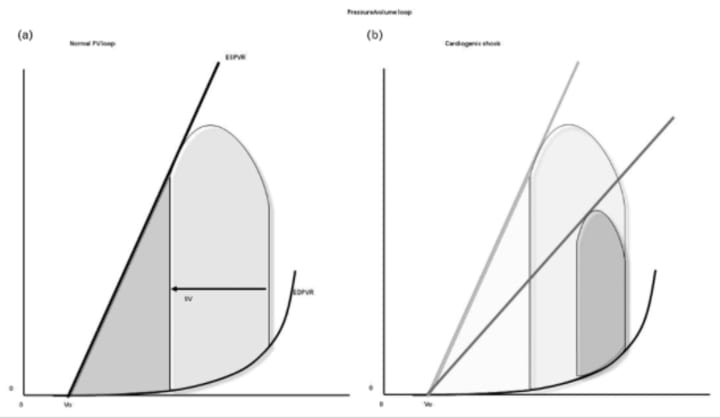

The PV ring is contained within the limits of the end-systolic and end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR and EDPVR) (Figure 2A). When the ventricular contractility drops rapidly, the ESPVR moves down and to the right. BP (the reduced height of the PV ring), stroke volume (the reduced width of the PV ring), and cardiac output will automatically be greatly reduced due to the decrease in ventricular contractility (Figure 2B). The left ventricular end diastolic pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure can also be seen to increase.

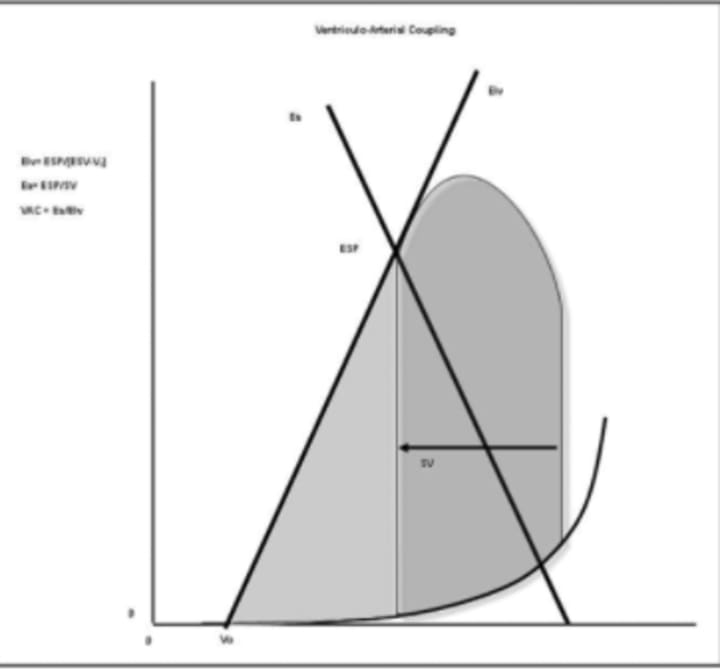

The slope of ESPVR is called left ventricular elasticity (ELv), which is equivalent to left ventricular contractility. The slope of the straight line connecting the end-systolic volume/pressure point and the end-diastolic volume/zero pressure point on the PV plane is called arterial elasticity (Ea) and is related to afterload. The relationship between Ea and ELv is called ventricular-arterial coupling (VAC) (Figure 3), and its values are close to the same under physiological conditions. However, under drastically changed hemodynamic conditions, decreased contractility and/or increased afterload will lead to increased ventricular-arterial coupling and increased myocardial oxygen consumption.

The role of ventricular-arterial coupling assessment in acute cardiogenic shock needs to be further explored. However, our experience in bedside assessment of ventricular-arterial coupling in patients with septic shock and experience in tracking and predicting hemodynamic response after treatment indicate that the development of left ventricular elasticity and ventricular-arterial coupling in patients with cardiogenic shock should be promoted. Joint bedside assessment research. Evaluating the heart-circulation interaction can provide insight into the pathophysiology behind hemodynamic monitoring data to further support clinical management and re-evaluation.

Baroreceptors are less sensitive to blood pressure and cause the efferent fibers of the autonomic nerve to release adrenaline from the adrenal glands. These factors increase the heart rate (thus increasing cardiac output), increase myocardial contractility, and cause vasoconstriction throughout the body.

Venous contraction is also an important part of the pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock. It will make the venous P-V curve shift to the left, and functionally transfer blood from the non-tension pool to the tension pool, thereby increasing the functional circulating blood volume to increase central and pulmonary vein pressure. In addition, these effects will cause the PV ring to shift further to the right and blood pressure will increase, but the effect on cardiac output is negligible. At this point, cardiac output is more susceptible to increase due to the drive generated by the increased heart rate.

Ventricular remodeling is driven by continuous neurohormonal activation and increased filling pressure, which is characterized by the gradual enlargement of the left ventricle but weakened function. On the PV plane, reconstruction manifests as ESPVR and EDPVR shift to the right, and manifests as overall changes in the size, structure and function of the whole heart in chronic heart failure

in conclusion

Cardiogenic shock is a long-standing disease that can lead to hemodynamic failure and patient death. Reasoning and understanding of the pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock is the cornerstone of formulating appropriate treatment plans and clinical management. Correctly identifying hemodynamic phenotypes and understanding the role of cytokines and inflammatory mediators are essential to avoid misunderstandings of hemodynamic parameters, prevent their disorders and limit their mortality. Advocate research on the heart-circulation interaction and the pathophysiological role of cells and proteomics in order to better understand the pathways leading to cardiogenic shock and better adjust the direction of its future treatment efforts.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.