One Step Back, Ten Steps Forward: A Brief History of Antibiotic Use and Development Around the Globe

T.J. Greer, MSML

As an Emory-trained medical historian, my fascination with antibiotics stems from their critical role in the practice of medicine. Though my previous research efforts were mostly focused on DDT, vaccines, and Parkinson's disease; antibiotics have caught my attention lately as conversations about "superbugs" have exploded. Understanding the evolution of antibiotics will surely help us understand the challenges and triumphs of healthcare professionals over the millennia.

Furthermore, I recently learned that a piece of Alexander Fleming's penicillin mold was auctioned for nearly $80,000. This extraordinary price reflects not only its historical significance but also the ongoing impact of Fleming's discovery on modern medicine. Such milestones remind me that the story of antibiotics is not just about science; it’s about how much people value the relentless pursuit of health and healing in the face of adversity (Bonhams, 2024).

1. Ancient Egypt (approximately 2650-2600 BC):

"Imhotep, the remarkable ancient Egyptian doctor, is known to treat infections with moldy bread" (Wainwright, 1996).

Empirical Evidence: "Dr. Armelagos and Dr. Nelson argued that the presence of tetracyclines [in Ancient Egyptian bones] were not simply artifacts. To support this, they used a technique called tetracycline labeling which is a technique that measures the concentration of tetracycline that is present in the bone. They found that 95% of Egyptian bones extracted had some form of tetracycline labeling, and 56% of these cases had more than 5% of their osteons labeled. This suggests that the Egyptian population must have been exposed to the antibiotic on a regular basis" (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2019).

2. Ancient China (around 500 BC):

"By using moldy soybean curds, China developed the first antibiotic used to treat boils" (Winter, 2020).

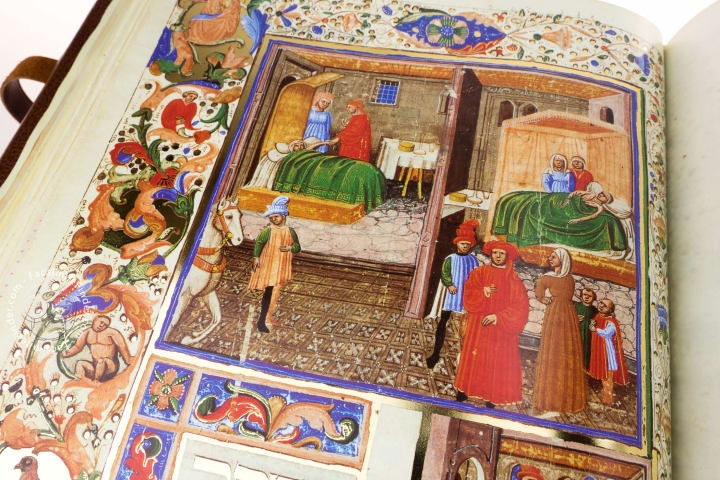

3. Medieval Europe (10th century)

"In 2015, our team published a pilot study on a 1,000-year old recipe called Bald’s eyesalve from “Bald’s Leechbook,” an Old English medical text. The eyesalve was to be used against a “wen,” which may be translated as a sty, or an infection of the eyelash follicle... In our study, this recipe turned out to be a potent antistaphylococcal agent, which repeatedly killed established S. aureus biofilms – a sticky matrix of bacteria adhered to a surface – in an in vitro infection model. It also killed MRSA in mouse chronic wound models" (Connelly, 2017)

4. Avicenna's Contributions (circa 1025):

"Avicenna , in his well-known book, Al Qanoon Fil Tib (The Canon of Medicine), recommended garlic as a useful compound in treatment of arthritis, toothache, chronic cough, constipation, parasitic infestation, snake and insect bites, gynecologic diseases, as well as in infectious diseases (as antibiotic)" (Bayan et al., 2014)

5. A Quick Discussion of Germ Theory (1860s-1880s)

Germ theory, developed in the late 19th century, revolutionized our understanding of disease causation. Pioneered by scientists such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, it proposed that microorganisms—specifically bacteria—were responsible for many infections (Brock, 2016). This marked a significant shift from the prevailing miasma theory, which attributed diseases to "bad air" or environmental factors. The acceptance of germ theory laid the groundwork for modern microbiology and fundamentally changed the approach to medical treatment.

6. Penicillin: The Miracle Antibiotic

“I did not invent penicillin. Nature did that. I only discovered it by accident.” - Alexander Fleming

"In 1928, Fleming began a series of experiments involving the common staphylococcal bacteria. An uncovered Petri dish sitting next to an open window became contaminated with mould spores. Fleming observed that the bacteria in proximity to the mould colonies were dying, as evidenced by the dissolving and clearing of the surrounding agar gel. He was able to isolate the mould and identified it as a member of the Penicillium genus. He found it to be effective against all Gram-positive pathogens, which are responsible for diseases such as scarlet fever, pneumonia, gonorrhoea, meningitis and diphtheria. He discerned that it was not the mould itself but some ‘juice’ it had produced that had killed the bacteria. He named the ‘mould juice’ penicillin. Later, he would say: “When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”

Although Fleming published the discovery of penicillin in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology in 1929, the scientific community greeted his work with little initial enthusiasm. Additionally, Fleming found it difficult to isolate this precious ‘mould juice’ in large quantities. It was not until 1940, just as he was contemplating retirement, that two scientists, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, became interested in penicillin. In time, they were able to mass-produce it for use during World War II" (Tan et al., 2015).

Today, we use penicillin to treat bacterial infections like strep throat, ear infections and urinary tract infections. They work by attaching to and damaging the cell walls of bacteria.

FDA-Approved Uses of Penicillin

"Penicillin G:

Anthrax caused by Bacillus anthracis

Actinomycosis caused by Actinomyces israelii

Clostridium infection in conjugation with antitoxin

Diptheria caused by Corynebacterium diphtheria with antitoxin

Fusospirochetosis caused by Fusobacterium species and spirochetes

Endocarditis caused by sensitive Streptococcus pyogenes

Rat bite fever caused by Spirillum minus or Streptobacillus moniliformis

Tetanus caused by Clostridium tetani with immune globulin and vaccine administration

Meningitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes, Meningococcus, and Streptococcus

Neurosyphilis caused by Treponema pallidum

Penicillin V:

Mild-to-moderate infections of the upper respiratory tract infection caused by Streptococcus and Pneumococcus

Scarlet fever and erysipelas (mild) caused by group A Streptococcus

Gingivitis caused by Bacillus fusiformis and Borrelia vincentii (along with appropriate dental care)

Benzathine Penicillin:

Preventing rheumatic fever

Treating syphilis (primary, secondary, and latent)" (Yip, 2024).

7. Significant Antibiotics Developed After Penicillin:

Streptomycin (1943) - The first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis.

Tetracycline (1948) - Broad-spectrum antibiotic used for a variety of infections.

Chloramphenicol (1949) - Effective against a wide range of bacteria; used in severe infections.

Erythromycin (1952) - A macrolide antibiotic, useful for those allergic to penicillin.

Vancomycin (1956) - Important for treating Gram-positive bacterial infections, including MRSA.

Ciprofloxacin (1987) - A fluoroquinolone antibiotic, effective against various infections, including urinary tract infections.

Azithromycin (1991) - Another macrolide, known for its long half-life and convenience.

Daptomycin (2003) - A lipopeptide antibiotic used for serious Gram-positive infections.

Linezolid (2000) - An oxazolidinone effective against resistant Gram-positive bacteria.

Ceftaroline (2010) - A cephalosporin with activity against MRSA.

8. Modern Advances in the World of Antibiotics (2020-2024)

Since 2020, groundbreaking research on antibiotics has focused on combating antimicrobial resistance and discovering novel compounds. One significant advancement is the development of new classes of antibiotics, such as teixobactin, which targets bacterial cell walls and has shown promise against resistant strains (Ling et al., 2015). Researchers are also exploring bacteriophage therapy, utilizing viruses that specifically infect bacteria, offering a potential alternative to traditional antibiotics (Gorski et al., 2019).

Another notable area of research involves the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to identify new antibiotic candidates. AI algorithms can analyze vast databases of chemical compounds and predict their effectiveness against various bacteria, significantly speeding up the discovery process (Stokes et al., 2020). Studies have highlighted the importance of combination therapies, where existing antibiotics are paired with adjuvants to enhance their efficacy and combat resistance (Kumar et al., 2018).

Advancements in genomic technologies have enabled scientists to better understand bacterial genomes and resistance mechanisms, allowing for the design of targeted therapies (Wright, 2017). Research on the human microbiome has revealed that certain beneficial bacteria can produce natural antibiotics, leading to potential new treatments (Haiser et al., 2014).

Overall, the period from 2020 to today has seen a surge in innovative strategies to tackle the growing threat of antibiotic resistance, aiming to secure effective treatments for future generations.

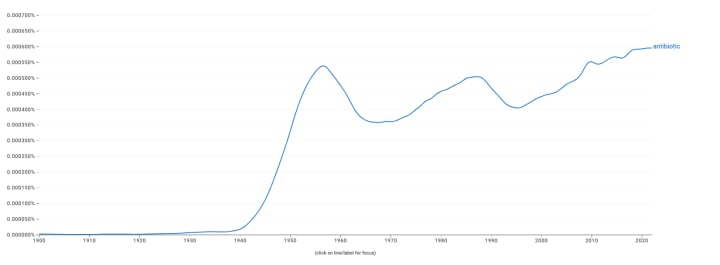

9. Google Ngram Viewer (Use of the Word 'Antibiotic' in 8 millions books from 1900-2024):

10. Bonus Section: Select African American Contribution

Meet Dr. Louis Tomkins Wright

References

Gorski, A., et al. (2019). Bacteriophage therapy: A new frontier in antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology. Retrieved from Nature Reviews Microbiology

Haiser, H. J., et al. (2014). Finding antibiotics in the human microbiome. Nature. Retrieved from Nature

Kumar, P., et al. (2018). Combination therapy strategies for antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. Retrieved from Nature Reviews Drug Discovery

Ling, L. L., et al. (2015). A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature. Retrieved from Nature

Stokes, J. M., et al. (2020). A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell. Retrieved from Cell

Wright, G. D. (2017). Opportunities for natural products in antibiotic discovery. Nature. Retrieved from Nature

Wainwright M. Biocontrol of microbial infections and cancer in humans: historical use to future potential. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 1994;4:123–131

Elsayad K. What Ancient Egyptian Medicine Can Teach Us. JCO Glob Oncol. 2023 Jun;9

https://www.vumc.org/lacy-lab/adventure-travel-guide-microbial-world/modern-antibiotics-ancient-egyptian-civilization#:~:text=They%20found%20that%2095%25%20of,5%25%20of%20their%20osteons%20labeled.&text=This%20suggests%20that%20the%20Egyptian,antibiotic%20on%20a%20regular%20basis.

Winter, S., & Bill, T. (2022). The future of genetic engineering in biotechnology. J Appl Biotechnol Bioeng, 9(1), 1-3.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/getting-medieval-on-bacteria-ancient-books-may-point-to-new-antibiotics/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/medieval-potion-kills-stubborn-bacteria-180975459/

Bayan, L., Koulivand, P. H., & Gorji, A. (2014). Garlic: a review of potential therapeutic effects. Avicenna journal of phytomedicine, 4(1), 1.

Brock, T. D. (2016). Milestones in Microbiology: 1550 to 1996. ASM Press.

Lax, E. (2004). The Mold in Dr. Florey's Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle. Henry Holt and Company.

Ventola, C. L. (2015). "The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis: Part 1: Causes and Threats." Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 40(4), 277-283.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). "History of Vaccines." Retrieved from CDC website.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). "Antibiotic Resistance." Retrieved from WHO website.

Tan SY, Tatsumura Y. Alexander Fleming (1881-1955): Discoverer of penicillin. Singapore Med J. 2015 Jul;56(7):366-7.

DW, Gerriets V. Penicillin. [Updated 2024 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan

About the Creator

T.J. Greer

B.A., Biology, Emory University. MBA, Western Governors Univ., PhD in Business at Colorado Tech (27'). I also have credentials from Harvard Univ, the University of Cambridge (UK), Princeton Univ., and the Department of Homeland Security.

Comments (2)

Addition 14 + 9 = ? 25 + 17 = ? 36 + 22 = ? 49 + 13 = ? 67 + 19 = ? Subtraction 97 - 43 = ? 75 - 29 = ? 99 - 67 = ? 123 - 56 = ? 216 - 139 = ? Multiplication 6 × 9 = ? 8 × 7 = ? 9 × 8 = ? 7 × 6 = ? 4 × 9 = ? Division 48 ÷ 6 = ? 63 ÷ 9 = ? 99 ÷ 11 = ? 120 ÷ 10 = ? 216 ÷ 12 = ?

EDIT: The first antibiotic, salvarsan, was deployed in 1910. In just over 100 years antibiotics have drastically changed modern medicine and extended the average human lifespan by 23 years. The discovery of penicillin in 1928 started the golden age of natural product antibiotic discovery that peaked in the mid-1950s. Matthew I Hutchings, Andrew W Truman, Barrie Wilkinson, Antibiotics: past, present and future, Current Opinion in Microbiology, Volume 51, 2019, Pages 72-80,