Episode 1 of "Awakening from the meaning crisis"

Paraphrased transcription and notes

These are my paraphrased transcription and notes (1) on the first episode of John Vervaeke's lecture series "Awakening from the meaning crisis". John is a Professor in the Cognitive Science Program of the Psychology Department at the University of Toronto. He also teaches at the Buddhism, Psychology and Mental Health Programme.

(Vervaeke 2019)

In this introduction to the series John recounts that the idea for the lecture series started with his observation that there seems to be a growing confluence between people who are interested in Buddhism and people who are interested in Cognitive Science (2).

John said that this can be seen in the world at large in the Mindfulness Revolution as for example described in the book of the same title edited by Barry Boyce and editors of Shambala Sun (2011)(3).

John points to the increasing public and academic interest in wisdom, currently a hot topic in Psychology and Cognitive Science (eds. Ferrari & Weststrate 2013). He refers to a popular book he bought for his son on how to be a stoic (Pigliucci 2017). John asks how is it that a philosophical position from the Hellenistic era has become a popular book that people are seeking?, why is there this hunger for wisdom? and why are people meeting it with these kinds of things? (4)

He refers to the increasing interest in psychedelics and psychedelic experiences including their efficacy in treating treatment-resistant addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder.

John highlights the shift in focus from happiness & mere contentedness towards meaning in life (Wolf 2010) as well as mystical and transformative experiences (Paul 2014).

In addition to the above, John refers to another set of dark factors that seem to be converging as well. These include societies going through mental health crises, expressions of nihilism and cynicism in individuals and groups, expressions of a deep sense of frustration and futility, abandonment of trust in public institutions, and a decline in religious affiliation and participation in clubs and organisations.

John and his co-authors Christopher Mastropietro and Filip Miscevic of the book Zombies in Western Culture (2017) argued there's an increasing sense of losing touch with reality, and proliferation of bullshit as technically defined by Harry Frankfurt (2005). We're spending too much time in our virtual environments with increasing evidence on the connection between various social media and increased depression and loneliness.

He said these also show up in the entertainment we seek and mythological forms we like such as zombies and superheroes. These to him are expressions of a cultural sense that we are stuck somehow. It shows up in narratives of crises, collapse, or the Apocalypse which used to be radical and confined to science fiction but has now become a pervasive background sense.

John considers that these are not mere coincidences but that there is a unifying explanation of why all these things, both positive and negative, are happening right now. This is the idea that our culture is suffering a profound meaning crisis. To John, this is not the only crisis we have but it relates to and is interdependent with other crises such as environmental and socio-economic. He said the lecture series will explore this.

John asks these three questions that he said will be asked again and again in the series (1) "what is this meaning that has come into crisis?", (2) "why do we hunger for it?", and (3) "how do we cultivate the wisdom to generate and enhance this meaning?".

Wisdom to him is realising (in both the sense of becoming aware and the sense of making real) meaning in life in a profound way. He said he is going to talk about this not just theoretically but practically as well. What are the practices people can and are engaging in (such as mindfulness) to cultivate wisdom?

John said he will give a historical account of what this meaning is that has come into crisis. We will get into the connection between meaning, wisdom and self-transcendence. Self-transcendence to him is a core need of a human being because it performs certain functions that are bound up with meaning and wisdom.

He said early in the series he will explore the connection between meaning, wisdom and self-transcendence with altered states of consciousness. Why do people and other intelligent organisms like Caledonian crows seek to alter their state of consciousness? Why does intelligence need to be conjoined with an altered state of consciousness? Why have humans in particular generated very sophisticated processes for generating, harnessing, and interpreting altered states of consciousness? This will be discussed in the series in connection with shamanism, ritual, flow state, being in the zone, and mystical experiences that can occur within psychedelic experiences (5).

John said that there is a subset of these mystical experiences that are very crucial. These are awakening experiences where people come back from the mystical experience and say "that is somehow more real than this and I need to change my world, I need to change myself"(6). They engage in what LA Paul has called a transformative experience—also known as quantum change, a radical transformation of their lives. He says we now have good research showing that they're right, their lives get better after these awakening experiences.

In bringing all of these together, John boldly proposes that perhaps we can have a cognitive, scientific account of what enlightenment is and why it alleviates the suffering from a lack of meaning.

In doing this he said we would also have to also tackle the darker aspects of meaning-making. He asks "what is the deep and profound connection between meaning-making and our endemic capacity for self-deception and self-destruction. Bullshit is a perennial threat to us. John says it will be important to talk about foolishness as something different from ignorance. To him, ignorance is a lack of knowledge, foolishness is a lack of wisdom. Foolishness is when one's agency, capacity to engage and pursue goals are undermined and threatened by self-deception and self-destructive behaviour that is a perennial vulnerability to cognition.

John will argue that the very same machinery that makes one so adaptively intelligent is the same machinery that makes one susceptible to foolishness (7).

This would take the series to tackle topics relevant to people's existential experience of the meaning crises. These include absurdity, alienation, futility, horror (when one's sense of grip on reality is being undermined which people find terrifying), meaninglessness, and the state of despair.

From these topics within the historical account of the origin of the meaning crisis, the series would move into the cognitive scientific study of cognition, the scientific investigation of meaning and meaning-making.

To John, when people use the word "meaning", it's a metaphor. They mean there's something in their life that is analogous to how a sentence has meaning. The pieces fit together in some way (8). They can impact one's cognition and connect one to the world in some way. There is something in our lives that is analogous to the way when a sentence has meaning. There is a need to unpack this metaphor. He asks "Why is this metaphor used?", "What is it that the metaphor points to when one talks about the meaning of one's life?", "How is it that some of the most meaningful experiences people have are precisely the ones that are completely ineffable to them, that they can't put into words?".

John says we would have to talk about different kinds of knowing where some of them have fallen off our cultural radar because of the meaning crisis. We tend to have reduced all of the ways that the ancients talked about how we know to one thing: to know is to have a special kind of belief. Because we have become so belief-centric, we as a culture became focused on ideologies (9).

We would need to have a more expanded notion of what knowing means. There's much more to knowing than having justified true beliefs. There's a kind of knowing that's involved in knowing how to catch a baseball. There's a kind of knowing of what it is like to be having this experience right now. There's a kind of knowing what it's like to be in something one is participating in like a relationship. John says that these kinds of knowing are important and integral to therapy, another thing that is booming right now. Part of why therapy is booming is the meaning crisis, part of it is people are seeking therapy because they are seeking to recover these lost kinds of knowing. These are the kinds of insights and transformation not of one's beliefs but of how one sees things, one's sense of self, and one's sense of realness (10).

These will give a structural-functional account of meaning. What is its structure? What are its cognitive processes? What are its cognitive mechanisms? How do they function? How can they fall into dis-function?

The historical account and the structural-functional account of the meaning crisis will be made to dialogue: inform, constrain, and enable each other (11).

From this dialogue could come a real response to the meaning crisis, an awakening from the meaning crisis. This is what the lecture series is about according to John. Not in some ideological fashion but in a profound transformative and existential manner.

He said this would not be something that he can do simply for this is not a problem for which there are simplistic answers. John said, "if anybody offers you an answer to this crisis in an hour, I would wager that they are deceiving you, manipulating or they are themselves significantly self-deceived". He said there's a reason why we're stuck, there's a reason why this is hard. This is a complex and difficult thing to be undertaken. John intends to carefully and responsibly build an argument to try and show how we can awaken from the meaning crisis, how this meaning crisis interacts with the mental health crisis, environmental crisis and socio-economic crisis.

John's stated commitment to the audience is that he will always do his best to offer rigorous, rational argumentation. He will try his best to give proper scholastic credit to other people. He said he is aware that he is not—and nobody should be— claiming to offer the absolute uncontested truth. He is going to offer good arguments, good evidence but he does not want the series to be an academic series. He wants it to be for people who are coming to this precisely because of a genuine, personal existential interest. He will try to keep jargon and technicalities to a minimum. He would have to introduce terms and he hopes to explain them carefully along the way. He said he cannot commit to being unbiased. To him, that's not a thing. What he said he will try to do is present his arguments and viewpoints and why he thinks they can be understood to be highly plausible.

John started with how and why this meaning is so much a part of our humanity.

He said that he had to start somewhere and that could be misleading. The deep connection between cognition and meaning may well be in a continuum that goes way back in our evolutionary heritage way before our humanity. He said that the fact that he is starting somewhere is not meant to indicate that this is the absolute starting point. John wanted to point to a time when many people think that the kind of people we are now came into form—the kind of humanity that we would recognise as us. And how much this was bound up with meaning-making.

This period is known as the "Upper Paleolithic Transition" that occurred around 40,000 BCE. To John what is interesting is that biologically we have existed much longer than this—since around a conservative estimate of 200,000 BCE. Around 40,000 BCE there was a radical change. At some point, we see things that human beings were not doing before. They were making representational art like sculptures, cave paintings, and music. He said there is good evidence that there was a significant enhancement in their cognition. There was the first use of calendars using symbolic representations of the phases of the moon and the passage of days. Human beings were keeping track of time across very abstract patterns to enhance their hunting activities.

The Homo Sapiens were developing projectile weapons in contrast to their contemporaries, the Neanderthals, who didn't have them. Neanderthals developed heavy stone thrusting tools that needed them to come close to their quarry and incurred injuries from close encounters with large angry mammals—as shown in bone damage evidence.

The Homo Sapiens started to do something different. They developed thin spears with bone tips. These were very light and very good as projectile weapons. They developed spear throwers and slings. They developed the ability to carry multiple missiles and project them at a long distance. These activities required increased development of one's frontal lobe area which turned out to be important in enhancing one's intelligence.

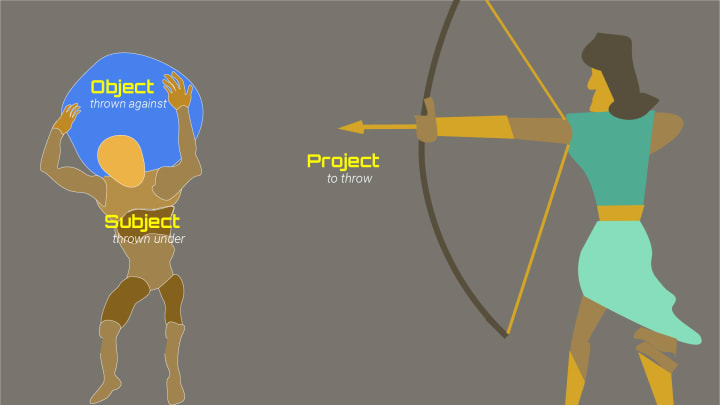

John says that this idea of throwing is deep in our cognition. This shows up when one talks about having a "project" one is working on. This is throwing. People will talk about "there's an object"—object means thrown against. Or when people say "I'm the subject"—subject means thrown under (12). He says all day long cognitively we are throwing. This is because this throwing task is such a complex task. We take it as trivial. There's a moving target, I can throw this and I can hit it. But attempts in artificial intelligence to do this turns out to be a really hard problem to solve.

John invites us to notice that all of these are associated with different aspects of what we mean by "meaning". Art and music are somehow "meaningful". Time was also being made meaningful—being measured and understood in calendars. Time and space became more meaningful because they were being used in a highly dynamic way in projectile weaponry.

John asks "What's going on?", "Why did it occur?". John says there's a lot of good work done on this including those by David Lewis-Williams (2002), Matt Rossano (2007, 2010), and Michael Winkleman (2010). John says that we know before the Upper Paleolithic Transition, about 30,000 to up to 70,000 years before, human beings almost went extinct. Humans were crunched down to around a maximum of 10,000 individuals. We almost died off. Part of it seemed to have been due to the overall climatic change of the end of the last Ice Age. Part of it could have been a supervolcano that exploded around 70,000 years ago (13). There was tremendous pressure put on human beings. Humans generally moved to the coast to try and survive. John said human beings seemed to have adopted interesting responses to this like they diversified their diet.

What's really interesting to John was that they came up with not so much a technological response—climate change was too huge and too poorly understood. It was that they came up with a socio-cognitive response. What humans started to do was to create broader trading networks. By doing this they were not as subject to individual environmental variation thus giving them access to more resources both in terms of what they can have and the discoveries they're making. Broader trading relationships broadened the scale at which human cognition has to operate in an important way. These humans probably developed things we see now as pervasive like rituals for dealing with the environmental challenge and the enhanced social network that they created to deal with them.

John says that he will talk a lot in the series about how cognition is very much participatory. We participate in distributed cognition—large networks of cognition. He said way before the Internet networked computers together, culture networked brains together in order to provide some of our more powerful problem-solving abilities. The rituals these humans developed include various trading rituals. John said we take it for granted that we live in cities. It is the deep presupposition of civilisation—we hang around with lots of strangers. This is a hard thing. Other species don't do this. There was a shift with humans beginning to interact with people who were not in their kinship hunter-gatherer group and had to form relationships with them. Humans then had to develop rituals that enhanced their ability to come into communication and relationships of trust for individuals they did not personally know.

According to John, this is why we still do stuff that does not make much sense today. We meet someone. We extend a hand. They grab it and move it up and down. This ritual was meant to show the other we're not holding a weapon. It allows the other to touch me and see if my hands are 'clammy' or not. The other can feel how tense I am. There are a lot of intuitive things going on. Most of us don't pay attention to all these anymore but they're there when we shake hands.

It's there when we ask how are you? This has become trivial. We actually don't want an answer. Originally this reflected something. We need to think about what important skills are needed to be enhanced for these rituals. I have to be able to take the other's perspective. I have to know what's going on in the other person's mind. I have to know how the other feels. I have to be able to move from a first-person perspective to a third-person perspective really well. If I can't do that then I will not be able to trade with the other person. This ability to take an enhanced perspective on others, especially people I don't know. This means I have to develop an ability that Daniel Siegel (2009) calls mindsight—the ability to pick up on other people's mental states. When I increase my ability to pick up on other people's mental states, I also increase my ability to pick up on my own mental states. This becomes part of the origin of things like metacognition and mindfulness.

John continues by explaining how the other set of rituals goes in the other direction. Trade rituals were for dealing with strangers. The problem becomes when one starts to interact with all these strangers, one's commitment and loyalty to one's group becomes more in question than they used to be in the past. It could have been taken for granted in the past because one was with one's group all the time. Now there were all these temptations from strangers—which have now become part of all our myths—the way which strangers can come in and tempt us. What to do? Humans created initiation rituals designed to show one's commitment to the group. These rituals often required risk, threat and sacrifice. Today's initiations rituals have been very tamed down. Initiation rituals in the past were often dramatic and traumatic. People were put in situations where they might experience tremendous pain or fear. Why make somebody go through pain and fear? Because if somebody goes through pain and fear it shows they are really committed to the group. What does this mean cognitively—how does the mind gets trained? It means improving one's ability to really regulate one's emotions. It means really improving one's ability to do decentering—to let one's self be in the hands of other people—a non-egocentric perspective. What's important during the ritual is not centred on one's self. The ritual is centred on the individual but through the ritual, the individual is being centred on the group. This has a tremendous impact on one's cognition (14).

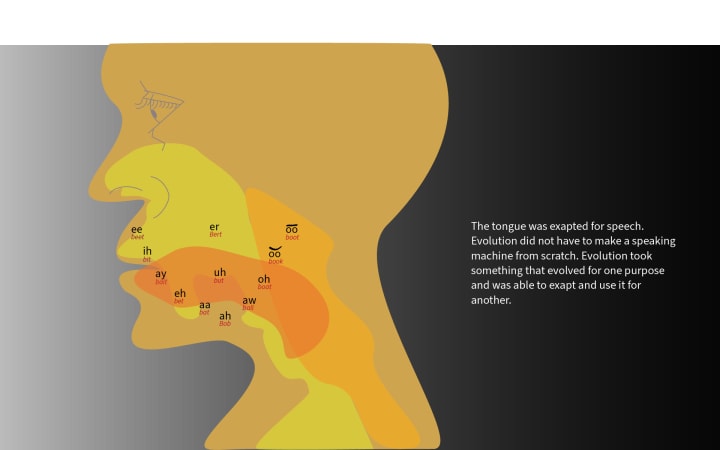

The third kind of ritual seemed to have also emerged according to John. It seems to have picked up on the cognitive enhancements that the trade and initiation rituals bring. This was brought in with the notion of exaptation—originally an idea from biology. The work of Michael Anderson (2014) has brought exaptation directly into understanding how the brain and cognition operates. Exaptation in biological terms is an evolutionary mechanism (15). As an example, we use our tongues to speak yet tongues did not evolve for speech. If tongues were evolved for speech then all animals with tongues would be speaking to us. Tongues evolved to move food around in our mouths. It is very flexible. And tongues are also poison detectors—a last-ditch defence for poison. The tongue has all these nerve endings. It is a highly sensitive and highly flexible muscle. The way humans evolved the tongue is situated along our air passageway. Evolution is not an intelligent designer. Using the same tube for air and food is a very bad design but that is how it is, how it evolved.

A flexible, sensitive muscle that can interrupt airflow—is what is needed for speech. The tongue was exapted for speech. Evolution did not have to make a speaking machine from scratch. Evolution took something that evolved for one purpose and was able to exapt it and use it for another.

What Michael Anderson and others are arguing according to John is that this is very often what the brain does. The brain develops a set of cognitive processes for one thing and the brain will re-learn to use that for something else totally different. A theme that will be talked about repeatedly in the series says, John.

What happened was that these enhanced mental abilities that were coming out of the trading and initiation rituals seemed to have been taken up into another set of rituals, exapted into, that seemed to be also pervasive. These were shamanic rituals.

John continues, we know that the ability to become aware of the mind, to control the mind, to control emotions, were being trained. We know that humans, just because they are highly intelligent creatures with sophisticated consciousness, seek out altered states of consciousness. In shamanism, there is a cultivated practice for altering one's state of consciousness that taps into and exapts this enhanced mindsight—this enhanced ability to manipulate and control one's mental and emotional states.

John says that Michael Winkelman's work (2010) shows that pervasive through hunter-gatherer groups were shamanic individuals. The shaman is such a pervasive historical figure that a good case could be made that it has become an archetypal figure. Something like the wise old man. Yoda, Merlin, these are all shamanic figures. What we know about shamanism was that it was the best healthcare humans could have for a long time. Having a shaman in one's group reduced discord within the group, enhanced the hunting abilities within the group. John with Rossano and Winkelman seek an alternative (to supernatural abilities, spirits and the like) explanation to why are shamans so effective.

John highlights how central shamanism was to the Upper Paleolithic Transition. A plausible case could be made that it was the advent of shamanism that helps to explain how human beings became capable of the sudden explosion in their cognition. John said this is the thesis of several people including Lewis-Williams (2002), Winkelman, Rossano and others.

This was not a hardware change. The brain was already existing for 160 thousand years prior. It was not changing significantly during the Upper Paleolithic Transition. It's much more likely it was not a hardware change but a software change in the brain on how human beings were using the brain. Shamanism probably played a big role in this software change.

John introduced the concept and term "psychotechnology". Technology is the systematic use of a tool. For example, a whiteboard marker is a tool. The first thing to understand John said is that in Andy Clark's phrase we are natural-born cyborgs (2003). The human brain evolved across several species to use tools. When we start to use a tool, even for a short period of time, our brains start to model it as a part of our bodies. This is why we can do things like we can feel the edges of our car when we are parking it. We have evolved to be integrated with machines (16).

John said to look at him and the classroom he is in. He said he is a natural-born cyborg. He said that the only natural thing in the room was the naked him. Everything else is a tool. Clothes are tools. No one is born with clothing. Clothes are used to modify one's ability to move through environments and carry stuff around. Spectacles, watches, shoes, tables, whiteboards, walls etc. are tools.

What is interesting to John is that this affinity for physical tools can be exapted onto cognitive ones. A physical tool fits one's biology and enhances it. A whiteboard marker can be grasped by the hand and be used to mark surfaces in a way not possible with bare hands. A bottle is graspable and can be used to carry liquids around in a quantity not possible with bare hands.

Similarly, a psychotechnology fits one's brain and enhances how it operates. An example is literacy. One is not born literate. One is born linguistic—learning how to talk (Chomsky 2002). For most of history, humans were completely illiterate. Literacy is a standard set of tools that standardise how one processes information. It enhances cognition. One does not have to hold what is written all in one's mind. One can leave them written on the whiteboard for example. One can write stuff down and come back to it later. One can link one's present brain functions and link them to those in the past and in the future. One can network all these instances together. One is improving one's cognition. One can also network his brain to another's brain, and improve one's ability to solve problems (17).

John suggested a thought experiment: what if we take literacy out of our brains— we're not able to imagine words, we can't put stuff on paper, and we can't reflect on our own cognition. The brain, the hardware stays the same but the range of problems we can solve collapses down dramatically. That's what psychotechnologies do. They enhance the software of our cognitive machinery.

According to John, shamanism is a set of psychotechnologies for altering states of consciousness and enhancing cognition. He also adds to the current situation the question: why is there a rise in neo-shamanism today? What are people thinking they are trying to get from it? (18)

The shaman does a lot of interesting things to get into a particular state. The shaman would often engage in things like sleep deprivation, intense long periods of singing, dancing and chanting. The shaman would often engage in imitation—put on clothing, and masks that represent some other figure or animal. Sometimes the shaman would engage in periods of isolation out in the wilderness. Though not necessary it has been pervasive, shamans would make use of psychedelics in order to help bring about an altered state of consciousness.

John referred to Steve Taylor's book "Waking from sleep" (2010) where the author discusses disruptive strategies people, even today, use in order to bring about awakening experiences—radical transformations in people's sense of self and reality.

One of the main ideas John said is that what a shaman is typically doing is trying to disrupt the normal ways in which one is finding patterns in the world. Why do this? It is because as previously mentioned the very thing that makes one adaptive also makes one subject to self-deception. The way one finds patterns is very profound.

John proceeded to demonstrate the 'nine-dot problem'. The task is to join all nine dots with four straight lines. One has to start the next line from the terminus of the last line. This turns out to be hard for many people to do. The solution is to go beyond the square to make non-dot turns. John said this is where the expression "think outside the box" comes from. Why this was hard was that one projected a pattern on the nine dots, and unconsciously engaged skills in connecting the dots learned from childhood where one is taught not to go beyond the boundaries of the shape to draw objects. One projected a pattern, activate appropriate skills then one is locked and blocked. One is unable to solve the problem. Not because of what is in the dots themselves, in the data, but because of how one framed it. One has to disrupt one's framing in order to get an insight.

John added that saying to people "think outside the box" does not help people with the nine-dot problem. Giving them the belief that they had to go outside the box does not help to solve the problem. This is what John meant when he said that one should not reduce all of one's sense of knowing to believing. What is involved in the nine-dot problem is not believing that one has to go outside the box, it's knowing how to go outside the box, how to alter one's attention, how to change one's perspective on what's salient, what's relevant, how to alter what's important or real to one's self.

Shamanism is, to John, a set of disruptive and attentional practices that are designed to disrupt everyday framing (19). This is so that the shaman can get enhanced insight. These include insight into patterns in the environment that other people may not be picking up on, and enhanced mindsight into other people. When the shaman is enacting the animal, the shaman isn't having beliefs about the deer, the shaman is becoming the deer. Not metaphysically according to John. But the shaman is trying to get together the sense of the skills, the kind of perspective the deer has, the way the deer thinks, the kind of world the deer lives in. And by becoming the deer, by having this participatory knowing of what it is to be a deer, it enhances the ability to track and find the deer.

With these enhanced capacities for insight and mindsight, participatory knowing, the shaman combines a lot of things that are separate for many of us as individuals. The shaman is highly charismatic. John asks us to imagine if we can take a rockstar, a super therapist, a super artist, put them all in one individual and they come to you when you are sick. They can enhance your ability to trigger your own placebo effect. John said that the placebo effect is real. John said thirty to forty per cent of all real medication, the ones sold as real drugs, is a placebo effect. If there is an individual that can trigger that, and that's all they had at that time, that's thirty to forty per cent better than what they had before.

Shamans are enhancing the capacity for cognition. John said that in the next episode he will come back to the shamans and talk more about what they're doing, how they're enhancing cognition, and why this played such an important role in making human beings into the kind of meaning-making beings they are. In order to tap into all these kinds of knowing, to bring about these altered states of consciousness, John invites us to notice how the shaman is manipulating the meaning of things. This is not the same thing as being a charlatan.

John ended this first episode by saying that right from the start, one can see the connections between meaning-making, altered states of consciousness, enhanced capacity to be in touch with the world. Then what is the connection to wisdom? The word "shaman" means one who knows, one who sees, one who has insight. Shamans are considered wise people. The word "wizard" means a wise person.

Notes

(1) I have listened to the entire "Awakening from the meaning crisis" once in the form of a podcast. This is my second time encountering the lecture series. This time from the YouTube channel. I watch the video and manually transcribe what John says. Not in verbatim but pretty much very close to what John has said. I also list down the books mentioned and have placed them either in my Scribd reading queue or borrowed the physical book from the library. I'm also using this series of transcription and notes to hone my skill in illustration. So I'm also using Adobe Illustrator to create some vector graphics to highlight points in the text.

(2) I suppose I'm a data point in this observation about people interested in Buddhism and cognitive science. I have a long-running interest in consciousness, cognitive science and artificial intelligence. At the same time, I'm currently studying Applied Buddhism after having finished Humanistic Buddhism at the Nan Tien Institute. You can read some of my writings on this topic in my Substack.

(3) I have started reading Boyce's book on the Mindfulness Revolution. So far I find it quite useful. It has a breadth of theory, practice and application of mindfulness. I'm liking the variety of authors in the collection of essays who are writing their take on mindfulness from differing traditions and points of view.

(4) A part of me is curious if there is a corresponding contemporary hunger for wisdom in African, Latin American, Islamic, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and other non-Anglo-American cultures. If there is, what books or tradition would they be turning to? Would they be turning to Hellenistic philosophy? Or would they be turning to philosophers from their own traditions? For example I was pleasantly surprised to know how the popular South Korean pop group BTS is influenced by the works of Carl Jung—in particular, Jung's Map of the Soul.

(5) I'm reminded of the book "Stealing Fire" by Steven Kotler and Jamie Wheal. The book is an exposition of how elite groups like the Navy Seals, Silicon Valley founders, adventurous scientists and extreme sports afficionados are "harnessing rare and controversial states of consciousness to solve critical challenges and outperform the competition".

(6) I personally have had this experience a number of times now in what follows after 5-MeO-DMT and psylocibin ceremonies as well as in deep meditation retreats. I partly describe my experiences in White and Ex stasis.

(7) I am reminded of what Daniel Schmachtenberger says about how the exponential technology in social media AI which currently is optimised simply for profit creates deliterious unitended consequences for individuals and societies. The same technologies can be re-factor to optimise individual and societal well-being. For example by tweaking the metrics and goals of the AI systems and what they are used for. See Daniel's conversation with Lex Fridman where they discuss this among other things.

(8) I remember Jordan Peterson using this metaphor—letters to phrases to sentences to paragraphs to chapters to books to collection of books...—in his lectures, and his tweets for that matter.

(9) I believe this is coming to head now in 2022 in the war between the virtualists and the physicalists as beautifully described by NS Lyons in "The Reality War" and "Reality Honks Back" and Mary Harrington's "Welcome to fully automated luxury gnosticism: Many of us are giving up on our bodies".

(10) I partly see this in the works of Bessel Van Der Kolk's "The Body Keeps the Score", Eugene Gendlin's "Focusing", Tor Norretranders's "The User Illusion", Johann Hari's "Chasing the Scream: the search for the truth about addiction", Antonio Damasio's "The Feeling of What Happens", Stephen Porges's "The Polyvagal Theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation", and Peter Levine's "Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma".

(11) This reminds me of how Joana Macy showed the congruence of dependent co-arising from the historicity of Buddhist traditions with the foundational principles of systems theory. For example, Macy likens the interplay of kāya and karma to the inter-determination of structure and function in systems theory where the structure is a record of past functions and the source of future ones, while the function is the behaviour of structure that at the same time enables the formation of new structures. See: Review of ‘Dependent Co-Arising: The Distinctiveness of Buddhist Ethics’.

(12) Guy Deutscher aptly characterised language as a "reef of dead metaphors" in his book "The Unfolding of Language: an evolutionary tour of mankind's greatest invention".

(13) Among other people, Graham Hancock posits the existence of civilisations much older than what is accepted by current consensus in archeology—as for example in his book "Finger-prints of the Gods".

(14) Daniel Schmachtenberger in this conversation with ZDoggMD on "Saving Civilization: Healthcare, Tech, Democracry" mentioned a story of him participating in a sweat lodge. One of the participants suddenly left when the space heated up. The shaman told Daniel that they did not trust people who leave the group in sweat lodges. This is because either he knew that the temperature was dangerously hot to the point of significant harm. In this scenario he just left his tribe to die. Or he knows it's not lethal but he has no ability to keep his panicked emotions in check.

(15) Stuart Kauffman in this lecture spoke about this as Darwinian pre-adaptations. He spoke about Darwin's example of the heart. The function of the heart is to pump blood. But we know that an organ with a function which is a subset of its causal consequences might find itself in a different environment. Causal consequences that are not functions now might be selected and a new function would come into exist in the biosphere. This is what a Darwinian pre-adaptation is. Stuart said this does not mean evolution had foresight. It just so happened. Stuart said Stephen Jay Gould wanted to get rid of the notion of foresight on the part of evolution so Gould came up with the word "exaptation".

(16) I would add to this that there are also psycho-social dynamics to technological progress.

(17) Literacy may also have deprived us of traditional memory abilities which we could probably reclaim as suggested by Lynne Kelly in her book "Memory Craft".

(18) An example of neo-shamanism is the growing and vibrant International School of Temple Arts (ISTA). I have done the Level 1 ISTA Spiritual Sexual Shamanic Experience training last May 2021 in Ivory's Rock, Queensland, Australia. It was perfect for what I needed at the time. I'm looking forward to doing the rest of the trainings in other countries in other continents.

(19) I am reminded of Kees Dorst's book "Frame Innovation: create new thinking by design" where, among other things, the exploration of how things are framed is purposely engaged to innovate out of complex conundrums.

References

Anderson, M 2014, After phrenology: neural reuse and the interactive brain, MIT Press, Boston.

Boyce, B (ed.) 2011, The mindfulness revolution: leading psychologists, scientists, artists, and meditation teachers on the power of mindfulness in daily life, Shambala, Boston.

Chomsky, N 2002, Syntactic Structures, 2nd edn, Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin.

Clark, A 2003 Natural-born cyborgs: minds, technologies, and the future of human intelligence, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ferrari, M & Weststrate, N 2013, The scientific study of personal wisdom: from contemplative traditions to neuroscience, Springer, Dordrecht.

Frankfurt, H 2005, On Bullshit, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Lewis-Williams, D 2002, The mind in the cave: consciousness and the origins of art, Thames & Hudson, London.

Paul, LA 2014, Transformative experience, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Pigliucci, M 2017, How to be a stoic: using ancient philosophy to live a modern life, Basic Books, New York.

Rossano, M 2007, 'Did meditating make us human?', Cambridge Archaeological Journal, vol. 17, issue 1, 30 January, pp. 47–58 https://www2.southeastern.edu/Academics/Faculty/mrossano/recentpubs/Did_Meditating_Make_us_Human.pdf

Rossano, M 2010, Supernatural selection: how religion evolved, Oxford University Press, USA.

Siegel, D 2009, Mindsight: change your brain and your life, Scribe Publications Pty Ltd, Carlton North, Victoria, Australia.

Taylor, S 2010, Waking from sleep: why awakening experiences occur and how to make them permanent, Hay House, London.

Vervaeke, J, Mastropietro, C & Miscevic, F 2017, Zombies in western culture: a twenty-first century crisis, OpenBook Publishers, Cambridge, UK.

Vervaeke, J 2019, Ep. 1 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Introduction, online video, YouTube, 23 January, viewed 23 January 2022, https://youtu.be/54l8_ewcOlY

Williams, D 2002, The mind in the cave: consciousness and the origins of art, Thames & Hudson, London.

Winkelman, M 2010, Shamanism: a biophysical paradigm of consciousness and healing, Praeger, Santa Barbara.

Wolf, S 2010, Meaning in life and why it matters, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

About the Creator

Oliver James Damian

I love acting because when done well it weaves actuality of doing with richness of imagination that compels transformation in shared story making.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.