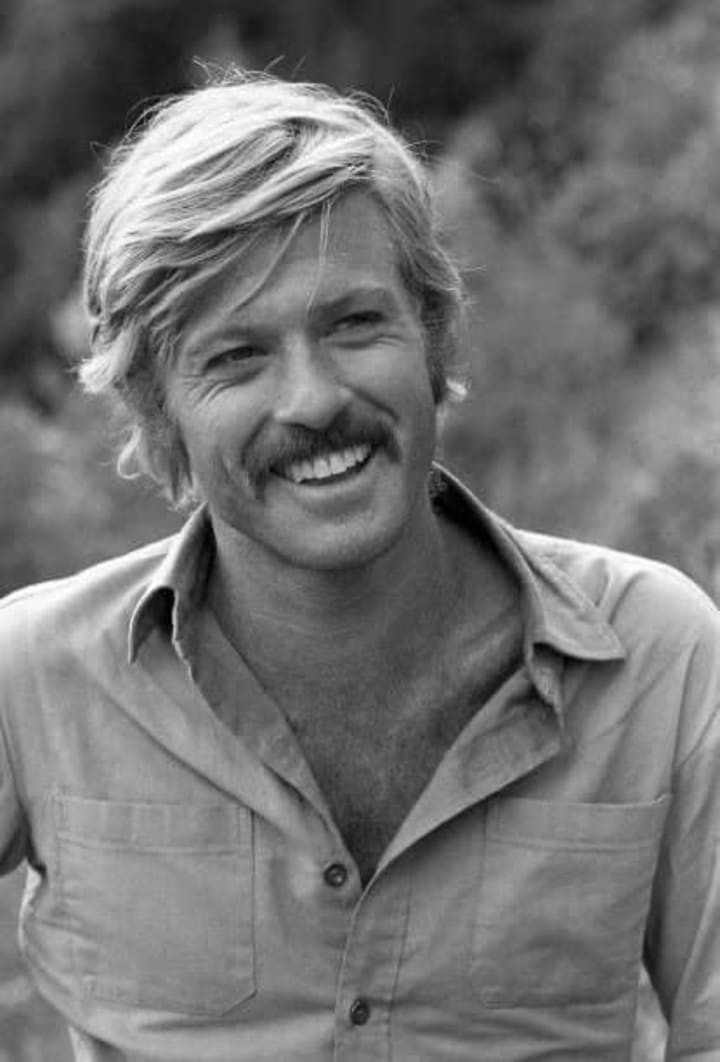

The Death of the Last Leading Man: Robert Redford and the End of an Era

Robert Redford died on September 16, 2025, in Provo, Utah, at the age of 89.

With him, a door that had stood ajar for decades finally closed: that of the last actor able to be both a star of the system and a critic of its foundations. His publicist confirmed that he died “in the place he loved, surrounded by those he loved,” but the ritual phrasing couldn’t begin to explain the magnitude of what was lost with his passing.

Over eight decades, Redford had been many things: the golden-haired leading man who defined 1970s screen masculinity, the Oscar-winning director of Ordinary People, the founder of the Sundance Institute who reshaped the landscape of American independent film. But above all, he was the architect of a form of stardom built on contradiction: using physical beauty as a tool to analyze the mechanisms that turned that beauty into merchandise.

His career stretched from the twilight westerns of the sixties to today’s streaming platforms, but two films from the 1970s crystallized his method: The Great Gatsby and The Way We Were. In both, Redford played men trapped between what they desired and what they could attain—between illusion and reality, between the American myth and its concrete workings.

The crucial difference was how each character resolved that tension.

The Man in the White Suit

The Great Gatsby reached theaters in 1974, directed by Jack Clayton from a script by Francis Ford Coppola, at a moment when Hollywood was adapting literary classics with the same epic ambition it had applied to The Godfather. The result divided critics but fixed Redford’s image as the definitive interpreter of American myths.

Clayton understood that Gatsby was not simply a character, but the embodiment of a core American contradiction: faith in self-reinvention versus the evidence that the past drags us like an irresistible current. Redford built Gatsby as a problem in emotional engineering: every gesture calibrated to transmit contradictory information, every silence loaded with meanings that accumulated without ever quite resolving.

The white linen suit clung like a second skin, signaling both class aspiration and the artificiality of that aspiration. His hair, slicked back with a perfection that seemed to require multiple mirrors, gleamed beneath the West Egg party lights as if it were one more element of the production design. But his most sophisticated work appeared in the quiet moments: the scenes of Gatsby contemplating the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock played like meditations on the nature of impossible desire.

In the reunion at Nick’s house, Redford achieved something technically complex: he conveyed that Gatsby was a professional actor playing the part of Jay Gatsby—that his entire identity was a conscious construction designed to recover a past that likely never existed as he remembered it. The man was forever rehearsing for an audience that never arrived, and Redford sustained that performance-within-a-performance without tipping into meta-theater or self-awareness.

It was a performance that demanded delicate balance: Gatsby had to be convincing as a millionaire and transparent as an impostor, attractive as a man and unsettling as a symptom of a broader cultural illness. Redford solved the equation by maintaining multiple levels of meaning in every scene, allowing viewers to build their own version of the character without any single reading becoming definitive.

The Wisdom of Retreat

The Way We Were had arrived a year earlier, in 1973, directed by Sydney Pollack, and approached the problem from the opposite angle. If Gatsby represented the obstinacy of desire, Hubbell Gardner embodied the philosophy of intelligent accommodation. The film traced the relationship between Katie Morosky (Barbra Streisand), a politically active Jewish woman from a working-class background, and Hubbell, a writer from a well-off family, from their college years in the thirties through the Hollywood blacklist of the fifties.

What made the film more than a conventional romance was the way each character represented a complete worldview for navigating a world that constantly disappoints us. Katie was absolute political commitment—the belief that people must fight for their principles regardless of personal cost. Hubbell stood for something subtler: a sophisticated survival mode that required knowing when to engage and when to withdraw, when to fight and when to accept that some battles cannot be won.

Politics wasn’t mere backdrop; it was the dramatic engine: the incompatibility between someone who believes that “people are their principles” and someone who believes that “people matter more than their principles.” In the climax, when Katie insists on protesting the witch hunts and Hubbell asks her to think of their family instead of abstract causes, the conflict transcends the personal and becomes a debate about responsibility in civic life.

The final scene—a chance encounter on a New York street years after the divorce—served as a demonstration of the Redford method’s effectiveness. In a few minutes of dialogue, he conveyed the entire off-screen history of a relationship: the marriage, the compromises, the final acceptance that their worldviews were irreconcilable.

The Actor Who Refused to Be Ken

What few knew at the time was Redford’s initial resistance to playing a character he considered underdeveloped. As Barbra Streisand writes in her memoir My Name is Barbra: “Bob was concerned that the script was so focused on Katie that the character of Hubbell wasn’t well developed. (He was right.) Bob asked Sydney, ‘Who is this guy? He’s just an object… He doesn’t want anything. What does this character want?’”

The objection revealed both his technical grasp of dramatic construction and his instinctive refusal to become what he himself would later describe as “a Ken doll—and that was for somebody else.” It wasn’t enough to be the handsome man who stayed quiet while the protagonist drove the drama. Redford insisted that Hubbell possess a philosophy of his own, a specific way of understanding the world that justified his seemingly passive choices.

The adjustments that followed turned Hubbell into a more complex figure: someone who had developed non-confrontation as a strategy of social survival, who had learned to navigate institutions without fully binding himself to any of them. His apparent surface revealed itself as a refined emotional intelligence—a capacity to sustain distance from the passions consuming those around him.

The result was a performance that transformed the character’s apparent limitations into narrative strengths. Hubbell wasn’t the obstacle keeping Katie from happiness; he was a man who had forged a different way of relating to the world, equally valid yet incompatible with hers.

Two Currents, One Actor

The comparison between Gatsby and Hubbell illuminates the broader strategy Redford crafted to position himself in American cinema as an interpreter of the nation’s fundamental tensions. Both men shared privileged origins and an education that prepared them for social power, yet they offered opposite responses to the central problem of American disillusionment.

Gatsby turned disillusionment into fuel for an impossible enterprise: reclaiming the past through the systematic application of will and money. Every West Egg party was a dress rehearsal for the moment Daisy would see that they could “repeat the past,” that five years of separation could be erased by the correct application of wealth and desire. It was heroic and self-destructive—a quintessence of American individualism driven to its logical extreme.

Hubbell made disillusionment the organizing principle of his relationship with the world. He had learned that love doesn’t guarantee compatibility, that good intentions don’t erase fundamental differences of character, that sometimes the highest form of love is knowing when to let go. His wisdom was less dramatic than Gatsby’s, but perhaps more sustainable: the recognition that life has rhythms of its own that often contradict our deepest wishes.

Redford played both men with the same technical precision, and what was remarkable was his ability to convey entirely different life philosophies without judging either one. He didn’t condemn Gatsby’s romantic obstinacy or Hubbell’s emotional pragmatism. He presented them as two equally human answers to the universal problem of how to live in a world that rarely matches our expectations.

The Architect of Alternatives

That duality became the foundation for Redford’s work not only as an actor but as a cultural entrepreneur. In 1981 he founded the Sundance Institute “to foster independence, risk-taking, and new voices in American film.” It began with ten emerging filmmakers working with mentors in the Utah mountains and expanded into one of the most transformative forces in contemporary cinema.

The Sundance Film Festival became a launchpad for Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Steven Soderbergh, Gina Prince-Bythewood, and many others who defined the last few decades of film. But Sundance’s importance goes beyond the individual artists it supported: it proved it was possible to build viable alternatives to the dominant system without entirely forgoing participation in its benefits.

It was the institutional application of the same logic he developed as a performer: creating spaces where artists could maintain creative independence without sacrificing the chance to reach broad audiences. Sundance served as a refuge for filmmakers working outside the studio system, yet it accrued enough prestige and economic power to influence decisions at the major entertainment companies.

The operation demanded a delicate balance between idealism and pragmatism that very few actors of his generation sustained across decades. Redford found a way to be both insider and outsider—to set the rules of the game and question them at the same time.

The End of a Model

In March 2025, a few months before his death, the Sundance Institute announced that the festival would move to Boulder, Colorado, in 2027, closing a forty-two-year era in Utah. The news coincided with broader changes in the film industry that challenged many of the principles on which Redford had built his work.

Streaming platforms had altered distribution to the point that the indie/commercial divide Sundance helped codify was nearing irrelevance. Recommendation algorithms had replaced critics and curators as the filters determining what finds an audience. Marketing budgets had grown into factors more decisive than artistic quality.

In that context, Redford’s figure took on an archaeological dimension that transcends his importance as an individual actor or director. He represented a model of film career that depended on mediating institutions—festivals, critics, specialty distributors—that have lost much of their influence to the power of tech corporations.

His death marked not only the end of a singular career, but the conclusion of a period when it was possible to be a star of the system and a critic of its foundations at once—when there was room for the productive contradiction Redford made his specialty.

A Light Going Out

When Esquire UK asked him in 2017 how he wanted to be remembered, Redford replied: “For the work. What really matters is the work. And what matters to me is doing the work. I’m not looking back: ‘What am I going to get from this? What’s the reward going to be?’” It was an answer that distilled decades of thought on artistic posterity: the value of a film career lies not in trophies or grosses, but in the capacity to create works that retain their force regardless of shifting contexts.

There is something in the persistence of The Great Gatsby and The Way We Were that suggests Redford identified elements of American cinema that transcend technological and economic fashions. Both films remain touchstones for actors and directors working under conditions utterly different from the 1970s—not because they offer formulas to copy, but because they demonstrate character-building techniques that endure regardless of production context.

Today’s actors are, technically, more skilled than those of Redford’s generation; they have better training and more sophisticated tools. But very few seem interested in the kind of cultural project he represented: building a career that operates simultaneously as entertainment and as a critique of the system that produces that entertainment.

Perhaps that’s a generational worry—the natural anxiety of someone who has watched their heroes die and isn’t sure who will replace them. Or perhaps it’s something deeper: the sense that we’ve reached the end of an era that had room for complex heroes, for leading men who hesitated, for stars who used their beauty as an instrument of analysis rather than merely an object of contemplation.

The green light at the end of Daisy’s dock was, as Fitzgerald wrote, “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.” Redford understood that the light also served as a metaphor for the star system: an illusion of nearness that always keeps its distance, an object of desire that justifies persistence even though it can never be fully reached. His genius was to play Gatsby as a warning rather than an aspiration—to use the character’s beauty to reveal its structural emptiness.

With his death, that green light goes dark. What remains is the capacity to remember what it stood for: the possibility of inhabiting myth without being devoured by it; of turning entertainment into knowledge; of finding on our screens something more than distraction. In an age when algorithms decide what we see and technology companies control how we see it, perhaps it is enough to remember that once there were actors who used their beauty as a form of resistance—stars who refused to be Ken dolls, men who found ways to say something true about America while pretending to be someone else.

That, too, is a kind of green light: something to keep steering toward even if we know we’ll never quite reach it.

About the Creator

DramaT

Defective survival manual: confessions, blunders, and culture without solemnity. If you’re looking for gurus, turn right; if you’re here for awkward laughs, come on in.

Find more stories on my Substack → dramatwriter.substack.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.