The September Letter

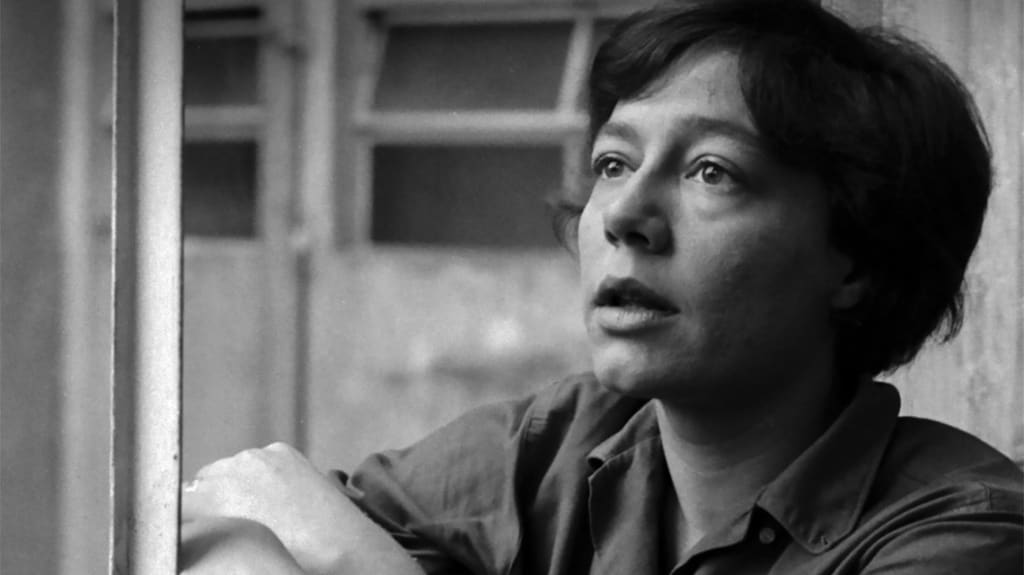

A work of fiction based on the final year in the life of the Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik

Pirovano Hospital, Buenos Aires

The envelope arrived the way all important things do: unannounced, when you’ve already stopped expecting them. Alejandra received it after one of those useless sessions with her analyst, where she had once again explained that no, there wasn’t a specific trauma, that her sadness had neither a birthdate nor a particular cause. It was simply there, like bones, like blood, like the things that stay with you from the day you’re born until the day you decide you won’t.

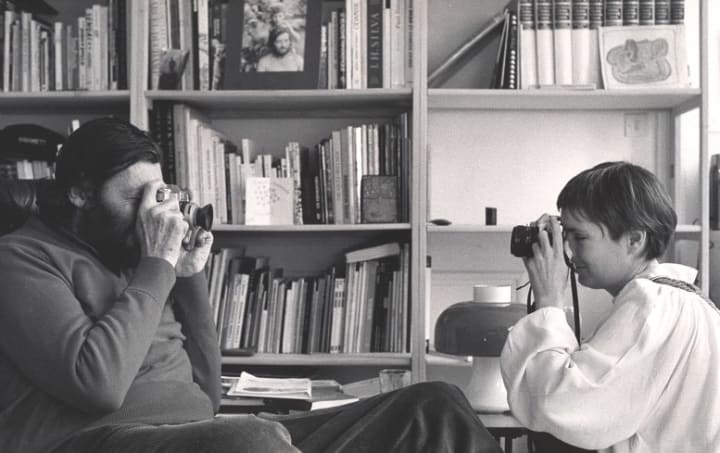

She recognized the handwriting on the envelope before she recognized her own breath. Paris. Him. The life from before, when she still believed other people’s words could save her own.

“Paris, September 9. My dear, your July letter reaches me in September; I hope by now you’re already back home”.

Home. A strange word in the mouth of someone who had never had one. The Buenos Aires apartment was merely a place to accumulate books and pills, a place to write poems about death for readers who were searching for life. Home was what other people had: mothers who didn’t terrify you, sisters who didn’t make you feel like the botched rough draft of something better.

“We’ve shared hospitals, though for different reasons; mine is quite banal, a car accident that nearly...But you, you—do you truly realize everything you write to me?

Of course she realized it. Every word she had put in that July letter was a small confession, an elegant way of saying that waking up was a daily punishment she no longer wished to serve. She had told him about the amphetamines that kept her awake to write, about the barbiturates she needed to sleep, about the chemical alchemy she had built to simulate functioning.

“Yes, of course you realize it, and yet I don’t accept you like this, I don’t want you like this; I want you alive, you mule, and understand that I’m speaking the very language of affection and trust—and all of that, damn it, is on the side of life and not of death”.

Alive. The word sounded to her like something said in a foreign tongue. When had she learned to be dead while breathing? Perhaps at four, when she began to stutter and words snagged in her throat like shards of glass. Perhaps when she discovered that women could also attract her and there was no place in the world for that truth. Or perhaps she had been born that way: with something disconnected, like an appliance that comes flawed from the factory and never learns to work properly.

“I want another letter from you, soon, a letter from you. That other thing is also you, I know, but it isn’t all of you and besides it isn’t the best of you. Going out through that door is false in your case; I feel it as if it were about myself”.

That other thing. He knew how to name it without naming it, the way we name the things that frighten us. But he didn’t understand that that other thing wasn’t a separate part that could be amputated. It was the very material she was made of: the dark substance running through her veins instead of blood, filling her lungs instead of air.

She folded the letter and tucked it away with the pills she had managed to hide. The paper felt like a relic from a world where it was still possible to believe in salvations.

A year later — The same apartment, the same darkness

Time at the hospital had passed like a film projected in reverse: the same days repeated to exhaustion, the same circular conversations with doctors who believed sadness had a cure. She had gone out and come back in, gone out and come back in, like someone who cannot decide whether to remain in a burning room or jump out the window.

Now she had a weekend pass. The doctors had noticed an “improvement” because she had stopped crying in sessions. They didn’t know she’d stopped crying because she’d stopped hoping.

She went to the chalkboard where she used to jot down verses, where words were born and died like flies in summer. She took the chalk and wrote slowly, as if carving an epitaph:

“I don’t want to go anywhere but to the very bottom”.

The sentence stayed there, alone, perfect. It wasn’t a poem; it was a statement of principles. A way of saying she had finally found the coherence that had always eluded her.

She had gathered the fifty Seconal pills with the patience of someone who collects stamps. One here, two there, saved up like someone setting money aside for a very special vacation. She counted them one last time, like a ritual. Fifty. A round, satisfying number.

She lay down on the bed with the same ceremony with which she had lain down every night for thirty-six years. But this time she wouldn’t wake with that feeling of having survived something she didn’t want to survive.

She thought of Cortázar’s letter, of those words about wanting her alive. He had never understood that “alive” was precisely what she didn’t know how to be. That she had been born with a blank instruction manual, like those appliances that never learn to function.

As the pills did their work, she had one final revelation: she hadn’t been crazy. She had been sane in a world that was madness. She had seen things exactly as they were: unbearable, beautiful, impossible to inhabit for someone born with her skin inside out.

Her poems would remain alive when she no longer was. That had always been the trap: she hadn’t come into the world to live but to make words live. To be the vessel that shatters so the wine can be poured.

The darkness approaching wasn’t death. It was, at last, the silence she had sought all her life: the only place where she would no longer have to explain to anyone why existing hurt so much.

“Night am I and we are lost”, she had written in her last poem. “Thus do I speak, cowards. Night has fallen and everything has already been thought out”.

And indeed, everything had already been thought. Everything had already been felt. Everything had already been suffered that a body can endure without breaking entirely.

Now there was only leaving left to do.

And she left.

About the Creator

DramaT

Defective survival manual: confessions, blunders, and culture without solemnity. If you’re looking for gurus, turn right; if you’re here for awkward laughs, come on in.

Find more stories on my Substack → dramatwriter.substack.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.