The Caretaker (1963)

A Review of the Film Based Upon the play by Harold Pinter

I could turn this place into a penthouse. For instance this room. This room could have been the kitchen. Right size, nice window, sun comes in. I'd have I'd have teal-blue, copper and parchment linoleum squares. I'd have those colours re-echoed in the walls. I'd offset the kitchen units with charcoal-grey worktops. Plenty of room for cupboards for the crockery. We'd have a small wall cupboard, a large wall cupboard, a corner wall cupboard with revolving shelves. You shouldn't be short of cupboards. You could put the dining-room across the landing, see? Yes. Venetian blinds on the window, cork floor, cork tiles. You could have an off-white pile linen rug, a table in... in afromosia teak veneer, sideboard with matte black drawers, armchairs in oatmeal tweed, a beech frame settee with a woven sea-grass seat... (sits up) it wouldn't be a flat it'd be a palace.

--The Caretaker

The Caretaker (1963) is a film about a brain--in actuality, it's about three men in an attic, but I can't, personally, see it in any other terms. Perhaps the word "brain' is incorrect here; a better term might be consciousness, divided into three warring parts, stuffed into a place of memories, dripping refuse, and odds and ends, that is claustrophobic, because vibrating (like the soundtrack) with the little creaks and groans and strange noises of our inward selves.

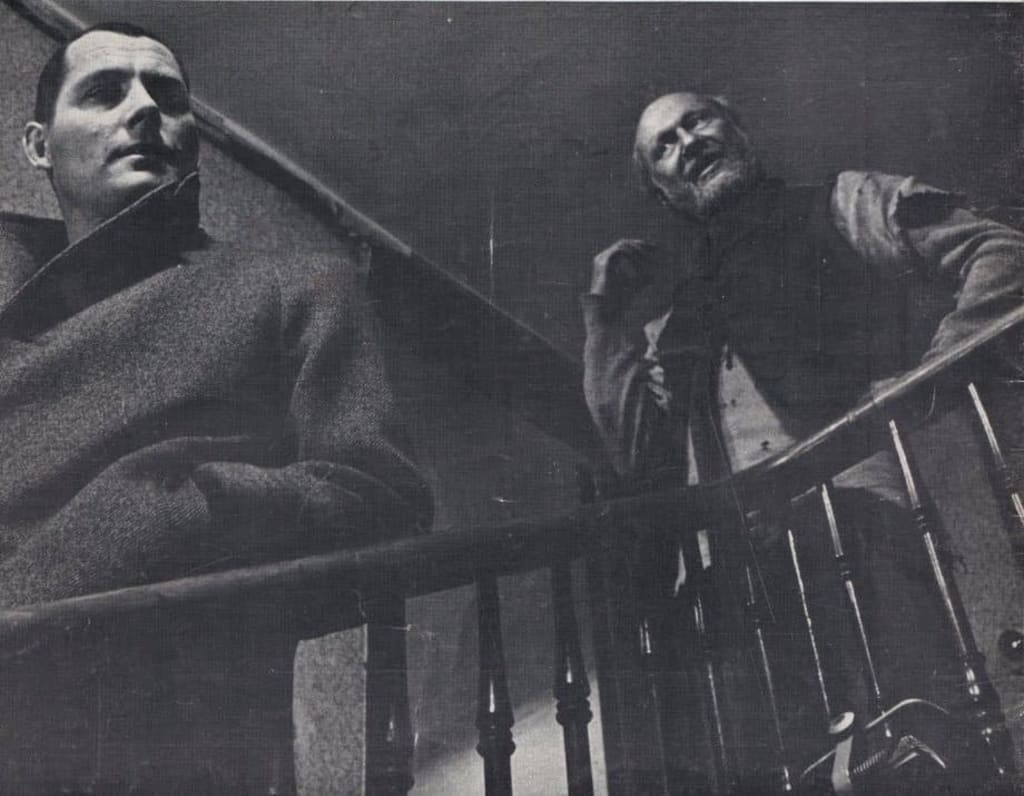

Donald Pleasance plays a filthy vagrant that looks as if he stepped from a Dickens novel. In the wee hours of a chilly English morning, he accompanies Aston (Robert Shaw) through the cold, desolate, and dark streets, just before sunrise. Aston is a quiet, reserved, "gentle giant," a tall and handsome fellow well-dressed and well-groomed. By contrast, Pleasance is dirty-looking, shabby, slaps his hand in anger, and is given to outbursts and exuberance. Before, we have seen Aston's brother Mick enter a home and look about an attic room in the pre-dawn darkness. Peculiar.

Aston takes Mac Davies (also known as "Bernard Jenkins") up to the same attic room, a cluttered, dripping, somehow stifling place that looks as seedy and uninviting as the inside of Pleasance's head must be. This is the interior of Unseen Character's skull, and inside, Aston's most prized possession is, unsurprisingly, a Buddha statue.

The film is driven by dialog, not action, and piecing it all together to make a coherency is a bit much, but, suffice it to say "Mac Davies" or Bernard Jenkins, or whoever he is, is revealed to be not only a man who seemingly has a racist phobia of blacks but makes of himself a perpetually angry hypertensive spectacle who thrusts his fist into his palm to punctuate every sentence with agitated force. To borrow from Orwell, also, he appears to have "dust in the creases of his face." Very dirty; one wonders how Aston can tolerate his presence.

Aston invites the homeless man to stay the night. He offers him tobacco, shoes, and, eventually, the care and upkeep of the house (why everyone sleeps in the attic is never explained, but, again, we revert to metaphor in our assessment of the location); enter Mick (Alan Bates), an aggressive, even hostile young and handsome fellow, who reminds one a little of a young Mel Gibson. Mick does not appear to welcome the intrusion of Mac, saying he "stinks from asshole to breakfast," and that he doesn't want him there, fouling up the place. Mac understandably does not want to get kicked out but protests lamely that he's freezing from the draft coming through the window. The wind, perhaps the thoughts penetrating the consciousness, Mac: a stand-in for all the repressed, ugly, dirty, malignant, and even helpless aspects of the psyche, one that cannot tolerate the cruel cold that Aston, the benevolent "higher self" does not at all find troubling. We later find that Aston, that gentle giant, was institutionalized, given electro-c0nvulsive therapy, a fact he denotes with the transcendent reserve with which Robert Shaw plays the character; cold, emotionally detached; as if he is simply not all with us, in total.

By contrast, Brother Mick is a hot-headed fellow, a kind of shoot-from-the-hip, witty, and loquacious "angry young man" who looks as if he could socialize with others in a way that his brother and Mac could not. He has a sarcastic wit and is not afraid to be forceful and harsh; he introduces himself to Mac at the point of a knife, thinking him an intruder.

All of these men are consumed by personal dreams. However, one wonders how they may border on the delusional.

Brother Aston, who "likes to work with his hands" (and can be seen frequently deeply contemplating a bit of wood, or some other piece of furnishings to refurbish), has a dream of "building a shed" out back. Mac wants to "get down to Sidcup," to "get his papers"; to prove his identity, and to, one supposes, get off the street and "get himself together."

Mick stares out the window dreamily, wanting to "start his own business." Will any of these men move beyond the confines of the attic, the cluttered, stifling upper room of their delusions, their prisons of the self? Can these three personalities (rough equivalents of Id, Ego, and Super-Ego) integrate into one cohesive whole? Who will be "the Caretaker" of the brain-space, the attic, help clean it out of its dross, and realize those dreams that beckon, that call, but that may be, finally, nothing more than personal illusions?

The film ends on an indeterminate note. The soundtrack, by the way, is pure musique concrete: pinks and plonks, the occasional weird synthesizer note. It's as understated as Aston; the creaks and groans of the otherwise silent brain space. (At one point, we note, also, that the Buddha statue is smashed.)

All of the performances are flawless; Pleasance is especially memorable, if only because he is the embodiment of seedy, shabby deterioration, the ugly underside of all of our hopes and fears. The other men are handsome and even dapper by comparison, but the despair of Aston and the angst of Mick are still real and palpable. If a man's mind could be divided into three, and personified, put into a living space, then The Caretaker is the artistic expression that might result.

The film was financed by such then-living celebrities as Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, and Noel Coward. It's a small film, but a powerful piece nonetheless, and utterly engrossing. As a final note: I dreamed of the title "The Caretaker" one night, and that's how I came to discover it.

I was on the set of a production of a stage play based upon The Elephant Man, but this was called Tusk [1], or Mr. Tusk, and had a fellow walking around with a sort of bamboo cage on his head, in a Victorian basement room, with a few nurses milling about, and enormous, tusk-like teeth. I hear a sort of rumbling and, going into the next room, begin to ascend a staircase, wherein two Max Fleischer Superman cartoon dames from 1941 come rushing down the stairs, telling me, "The Caretaker is coming!"

And I got up, sought out that title, and discovered this buried treasure of the British cinema, this piece of "kitchen sink realism"; this stage play of the mind.

Wonders never cease. In the attic of our Brainscape, we can live lives of desperation, And we can also dream.

[1] By the way, Tusk is an actual film, with Johnny Depp, about a man forcibly transformed, through surgery, into a walrus. I haven't yet had the pleasure.

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.