Such Varied Ukrainian Puritanism: A View Through the Literature of Taras Shevchenko

Between Lutheran severity and Ukrainian sincerity lies a bridge — built by Shevchenko’s pen

For me, a Ukrainian Protestant who converted from Orthodoxy at the age of sixteen, Protestantism at first appeared as a more secular and freer form of Christianity. But the deeper I explored this doctrine, the more I discovered the great glory of the reverence for labor and the Puritan ethic.

Alongside my study of Protestantism, I always held great respect and interest for my native Ukrainian culture. And when I began studying Ukrainian philosophers and writers, I started to notice resonances between my newly discovered Protestant truths and the voices of my own culture. I began searching for traces of my new worldview within Ukrainian heritage.

At the heart of that heritage stands one central figure: the artist, writer, and poet Taras Shevchenko. I borrowed from the library three of his novellas — The Artist, The Twins, and A Walk with Pleasure and Not Without Morality. To my great surprise, I discovered my own Shevchenko — a man who shares the same Puritan respect for labor and the world as I do. Yet he also diverges from it in significant ways.

And this, in essence, is what makes Shevchenko truly the father of the Ukrainian nation. He is the cultural father of every Ukrainian — of each unique and different Ukrainian.

In this article, I aim to explore this aspect of Shevchenko: his Puritan outlook and its divergences, and how Protestantism, rather than alienating one from Ukrainian identity, can in fact enrich it.

____________________________________________________

Shevchenko as a Mirror of Puritanism

Shevchenko speaks of the importance of hardship and the patience required in humble work as a foundation for personal growth. For instance, his novella The Artist begins with the example of the great sculptor Thorvaldsen, who once had to carve ship ornaments for Copenhagen’s docks. Shevchenko shapes his own protagonist in the same mold:

“My hero, though his career was less brilliant, still entered the artistic path by grinding ochre and mummy in mills, painting floors, roofs, and fences. A hopeless, cheerless beginning”

He emphasizes this with the line:

“And how many of you, lucky ones, artist-geniuses, have begun differently? Very, very few”

He goes on to list artists of the Dutch Golden Age, concluding with the phrase:

“They began and ended their great careers in rags”

Interestingly, Shevchenko backs nearly every thought with an example, as if writing a publicist’s essay rather than fiction.

As for Puritanism, Shevchenko here touches upon the vital principle of vocation — the acceptance of one's destiny and role in life. Each profession becomes a sacred offering to the world, a unique, challenging path through which one becomes a blessing — for others and for oneself.

This idea is a core Protestant principle. Shevchenko, of course, was educated and knew of Protestantism — he even mentions Luther in this very novella. But traditionally, the moral father of the Ukrainian nation practiced Orthodoxy, where the analogous principle is that of ascetic obedience.

“In a truly artistic work, there is something magical, more beautiful than nature itself — the exalted soul of the artist, divine creation. Yet in nature, too, there are such remarkable phenomena that the poet-artist falls to the ground and merely thanks the Creator for sweet, soul-enchanting moments”

Here, Shevchenko — as I see it — expresses reverence for nature by suggesting that even the most gifted artist is still vulnerable to its overwhelming beauty. This again reflects Orthodox asceticism, where man can accomplish much, yet nature and life retain a broader creative power — a power to awe and inspire the creator.

In essence, Shevchenko’s worldview forms a synthesis of Orthodox asceticism and the Puritan ethic of labor and humility.

____________________________________________________

Shevchenko as Anti-Puritan

For a Puritan, passion is often a hindrance on the path to a pure life with God. For Shevchenko, however, passion is the very path toward understanding one’s humanity — and thus, toward a truer life with God. This is where his Orthodox side takes center stage. In Orthodoxy, the path to God may run through suffering, passion, doubt, sin, and repentance.

“In this regard, I bear much resemblance to my unyielding countrymen. Our writers, and generally all decent folk, call this feeling willpower. But it could just as well be called ox-like stubbornness. It’s more vivid and expressive”

Shevchenko’s philosophy of faith is deeply compelling. He values labor and willpower as purifying forces, as in Protestantism — but also cherishes emotional experience: through tears, contemplation, and acceptance.

“And all this absurd expectation was getting in the way. What am I waiting for, and what is disturbing me? I don’t even know — but I feel something is disturbing me”

— A Walk with Pleasure and Not Without Morality

Another telling moment occurs when Shevchenko’s future student comes to meet him for the first time and attempts to kiss his hand. Shevchenko pulls it away — and this moment deeply unsettles the young man. Shevchenko explains his motivation like this:

“I greeted him and extended my hand; he lunged for it, wanting to kiss it. I pulled my hand back — his servility embarrassed me”

“‘You were angry with me. I got scared,’ he said.

‘I wasn’t angry,’ I replied. ‘But your humiliation made me uncomfortable. Dogs lick hands — people shouldn’t.’

This strong statement struck him so deeply that he reached for my hand again.

I laughed, and he blushed”

— The Artist

Here, for Shevchenko, freedom is not merely political — it is internal, spiritual.

____________________________________________________

What Has Modern Ukraine Inherited from Shevchenko’s Philosophy?

“I liked his modesty — or better to say, his shyness. A sure sign of talent”

— The Artist, when the student shows Shevchenko his first drawing.

This scene reveals the beauty of modesty and the hidden talent that so often lies beneath it. Indeed, a truly gifted person constantly strives for perfection, engaging with their own work critically and seeking to improve it.

One of the most vital Ukrainian traits drawn from this — one of Shevchenko’s key narratives — is modesty. From it stems a unique national feature: intelligentsia. For the British, this might manifest as the ability to collectively maintain moderate political paths without tipping into radicalism.

But Ukrainian intelligentsia, as Shevchenko shows us, lies in delicacy — in a fine-tuned ability to value not just results, but the inner state of the person behind them. This gives Ukrainians the strength to endure and overcome internal crises over the long run.

____________________________________________________

What More Can Shevchenko Offer Ukraine?

Ukraine is a vast land that has always stood at the crossroads of many worlds.

It could take from Shevchenko the trait of complex thinking. For his thought is truly a fusion of worldviews.

And this path — of intellectual synthesis — is one Ukraine must now walk. To build a space where not only the Ukrainian language matters, but also Russian, and any language in which people create. Where every Ukrainian, or person of another nationality writing a new poem on Ukrainian soil, will — first — uncover new facets of the old and rich Ukrainian culture, and — second — bring something new into it from themselves.

This, too, was my path. Where a shift in religious confession did not sever my roots — on the contrary, it made them deeper and more meaningful.

____________________________________________________

Literature referenced:

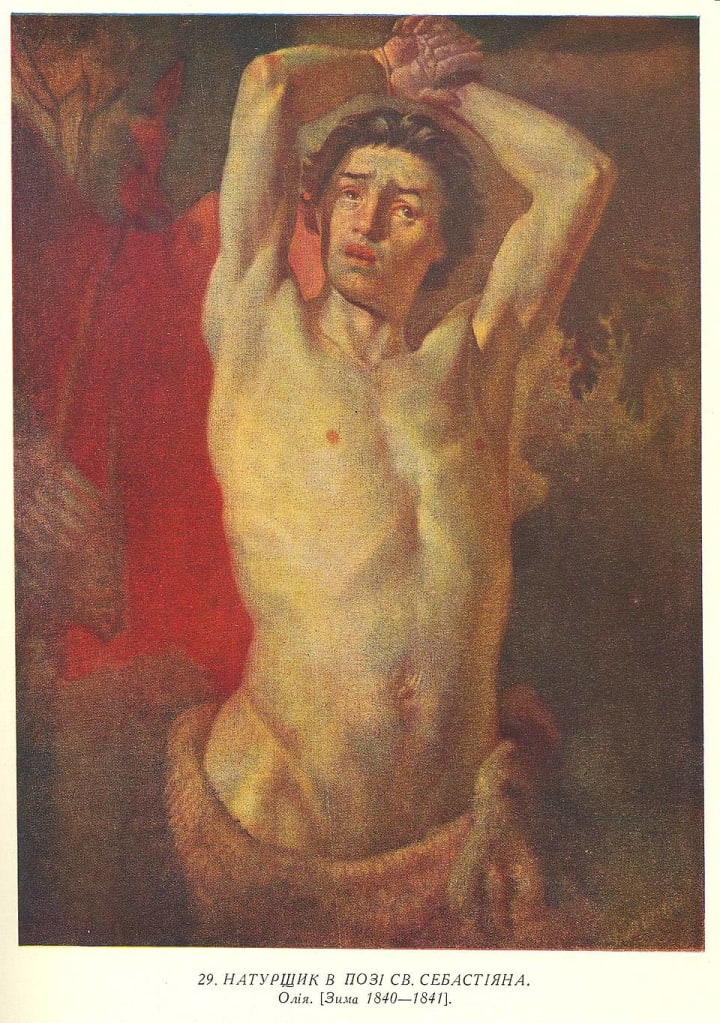

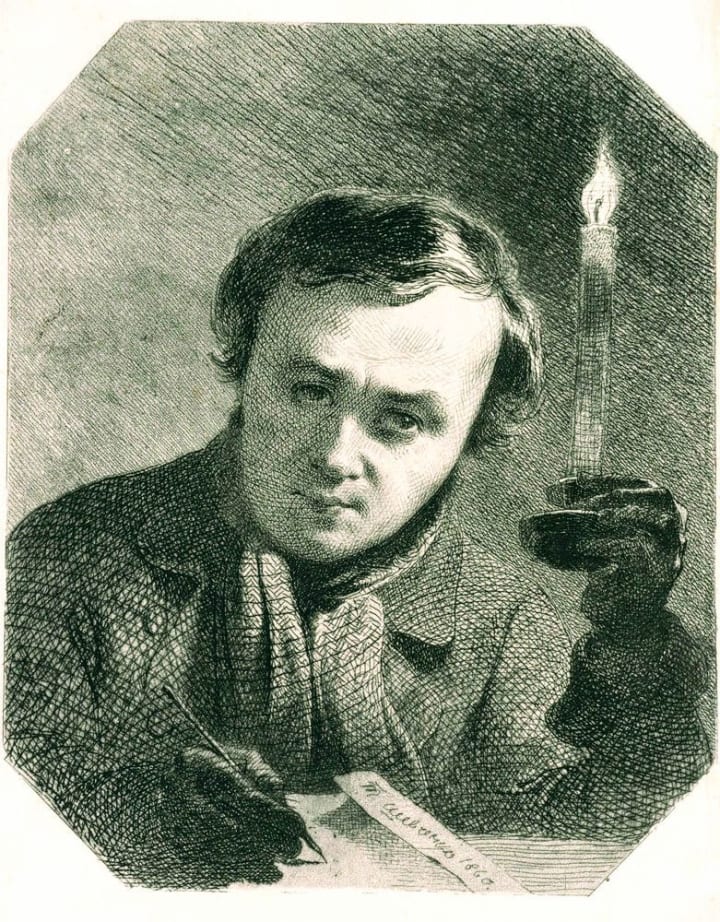

• Shevchenko, T. G. Novellas. The Artist. The Twins. A Walk with Pleasure and Not Without Morality / translated from Russian by M. Chumarna — Lviv: Apriori, 2015. — 320 p.: ill. — ISBN 978-617-629-120-6

About the Creator

Ilya V. Ganpantsura

Hereditary writer and activist, advocates for linguistic and religious rights in Ukraine, blending sharp analysis with a passion for justice and culture.

https://x.com/IlyaGanpantsura

https://ilyaganpantsura.wordpress.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.