South Asian Geo-Political Shifts: Past and Present

Introduction, History & Present Situation

I

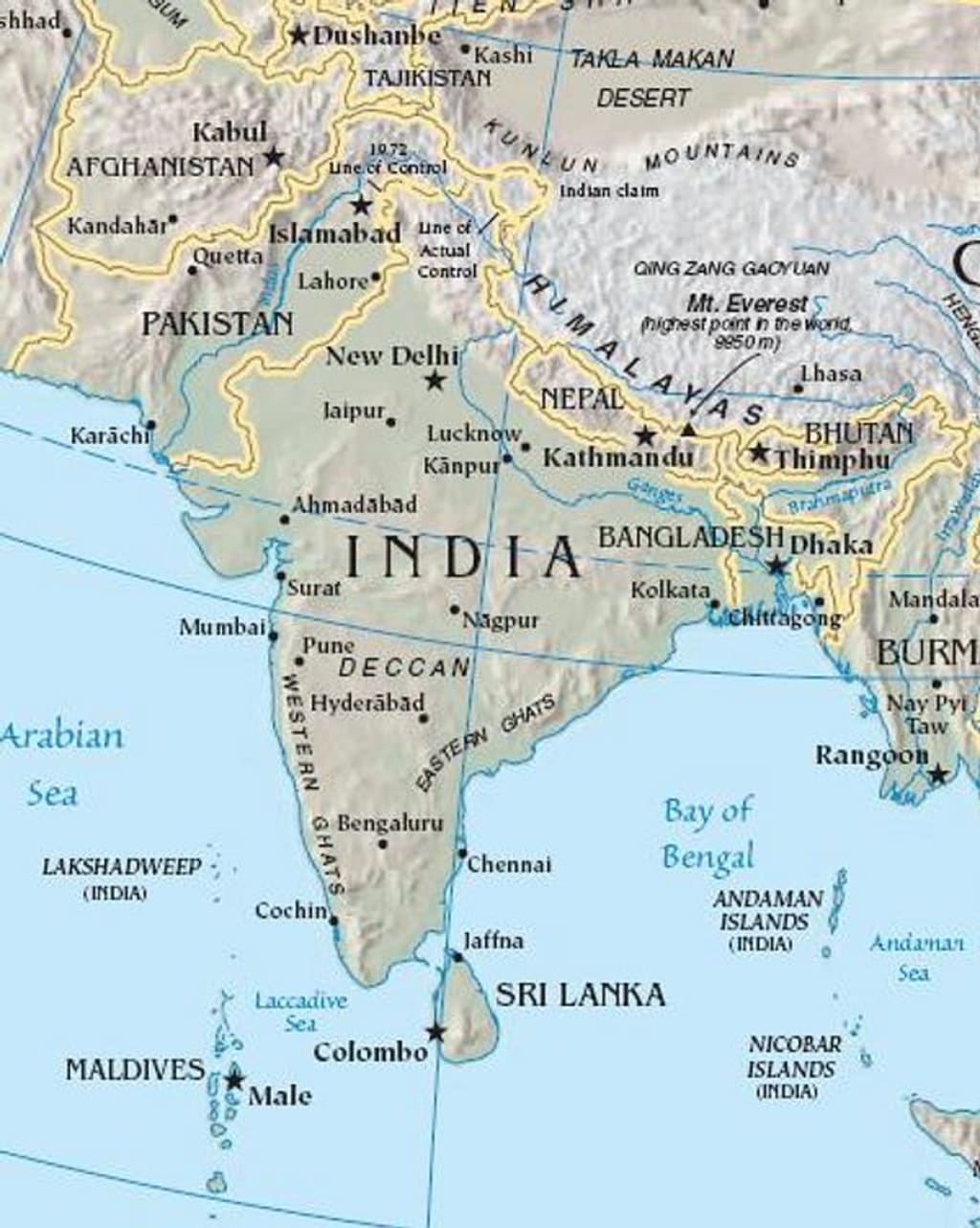

NBefore discussing the geo-political issues, for this paper, the South Asian (SA) concept needs to be clarified. Countries contiguous to the Indian Sub-continent and within the definition of ‘Indian Sub-Continent’ have been discussed. But countries of the Sub-Continent, mainly in the region between the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal are within the realm of South

Asian geopolitics. Therefore, two of the Island nations of South Asia, Maldives, and Sri

Lanka, are connected with the geopolitics of SA and have also been brought into the

framework as nations of IOR (Indian Ocean Region)

.

Geographic Features of the Sub-Continent/South Asia

The geographical features of the subcontinent as a whole are unique and occupy a dominating

place in global geopolitics. The geographical setup of the Indian Subcontinent is open from two

sides, west and east. But the north is bounded by one of the highest and the longest mountain

ranges of the Himalayas which makes it nearly impossible to cross except through limited

prominent passes. The most historical and famous pass within the range is the Khaybar Pass and

in the mid-west around Baluchistan is the Bolan Pass. Both passes connect the Sub-continent with

Central Asia through Afghanistan and Iran. It was the Aryans who are believed to first arrive at

the Sub-continent through these western passes in 1500 BCE. However, the first massive invasion

by foreign troops was through the Khyber Pass of Alexander the Great of Macedon in 326 BCE.

Since then, invasions in Central Asia appeared through these passes which instrumented the

establishment of the rules of various dynasties. Across the Northern Himalayas is a tract of Tibet

(now part of China) and North West is Xinjiang China.

Indian Sub-Continent has a huge land mass of around 4,440,000 sq km with a population of 1.8

billion. The land mass is bestowed by Indo-Gangetic plains17 with major river systems from the

West to the East. These river systems nourish from the Himalayan Glaciers and make the entire

Gangetic–Indus plains along with the plains around other river systems fertile and remain

cultivable throughout the years.

The trace of the first settlement and civilization still exists in the Indus valley of Mohenjo-Daro

and Harappa (Harappan/Indus Civilization18) proving the geopolitical importance of those ancient

times.

The South of the Sub-continent is bordered by one of the largest oceans of the world, the Indian

Ocean with an area of 70,560,00 square kilometers. The important strategic seas and the Bay of

the Ocean are, in the north and southeast, the Bay of Bengal, and the Andaman Sea respectively,

and in the west is the Arabian Sea, and in the southwest is the Laccadive Sea. Adjacent to the Sub-

continent is one of the most strategic and resourceful regions bordering the Sub-Continent is the

Persian Gulf which carries the bulk of the energy of the modern world to the east and the west

through the choke points of the Indian Ocean. Some of these choke points made the most contested

geopolitical real states since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, thus Bab El Mandap became

the hottest Choke point in the West. Other chokes like the Mozambique Channel, the Strait of

Hormuz, the Sunda Strait, and the Lombok Strait have been geopolitically important in the control of the Indian Ocean.

By the 19th century, the geopolitics of the Indian Subcontinent was fully exploited by the British

colonial rulers. By then, the Suez Canal shortened the distances from Europe to the Indian Sub-

continent. It was easier for the British sea power to control all the choke points that formed a string

of pearl around the Indian Sub-Continent. The newly opened Suez Canal served to further

accelerate the pace of communication into and out of the Indian Ocean. The British built major

naval bases at Simonstown at the Cape of Trincomalee in Ceylon which expanded to become vital

nodal points of power in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Kearney, 2004).

The British were dominating their colonies from east to west and controlled almost all choc points

to guard the Indian Ocean. As Amitav Chowdhury puts it, “Between the early exploratory

adventures of the late 16th and 20th century, the British in the Indian Ocean were a consistent

presence. In this period, much of the competition for global commercial hegemony, territorial

expansion, and the control of strategic vantages were played out in the ocean’s arena.” (. As on 01

June 2023)

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the British Royal Navy with the help of the Bombay

marines had defeated most of their French and Dutch rivals from the rim of the bay. The Suez

helped the Royal Navy to establish full mastery. On the other hand, they had controlled all the

atolls and Islands in the Indian Ocean, developed all facilities for agriculture, took the manpower

from India up to the Malayan Peninsula and Hongkong, and controlled the Malacca Strait. On the

east of India, the entire Burma was brought under British rule controlling all the ports. With the

un rivalled control of the Indian Ocean, the British remained the superpower controlling vast

tracts of the Middle, South, and East Asia until WWI when the USA started to emerge as a

superpower.

It was WWII when Britain became economically weak and the colonies started achieving their

freedom. The religious division of Hindu Muslims resulted in riots for a separate Muslim religion-

based country. The British India was divided in 1947. The rest of the Colonies within the northern

rim of the Indian Ocean got their independence from the colonial rule after India and Pakistan

came into existence like Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1948, Burma (now Myanmar) in 1948, and

Maldives much later in 1965.

With the withdrawal of the British from most parts of the Indian Ocean and its rim, less Diego

Garcia, a total of 38 independent countries became IOR (Indian Ocean Littoral) by the 1960s,

among which was India and situated both on the shore of Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, till

1971. India however, had geo-strategic ascendency over other littorals with strategically located

Andaman Nicobar Island in the eastern southeastern Bay of Bengal.

Re-shaping Indian Sub-Continent: Post-1947

The independence of the Indian Sub-continent resulted in the division into two countries with a

huge alteration in the geography. With the loss of Baluchistan and the North West Frontier

Province (NWFP), independent India was deprived of direct overland access to the Middle East

and Central Asia. No more than that, British India’s geopolitical readiness as Halford Mackinder

once mentioned in his geopolitical perception of the British Empire laying importance on the North

West Frontier19(Menon, 2021, p. 12) and the geopolitical perception of the ‘Great Game’20 if not

dead, carried no more geopolitical importance for India.

India and Pakistan on the West shared a 3,310 km border which includes the Line of Control (LOC)

in disputed Kashmir21

. The North boundary remained unchanged as India shares 3,488 km of

borders which includes 890 km of the ‘disputed McMahon line’22. This was agreed upon between

British India and Tibet at Shimla in 1914 but the dispute remains to date terming the line drawn

‘arbitrarily’ by the British Raj. On the other hand, China and India share borders with Nepal and

with Bhutan who maintained their freedom to a great extent during the British Raj in India.

On the East, the Indian border with East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) stands at 4,096 km. The part

became a wedge between India and the Indian North Eastern part only to be linked by the Indian

narrow corridor of the ‘Siliguri Corridor’23 which made it difficult for the rest of India to be

integrated with the North East with a hostile Pakistani part.

Independence of India and Pakistan

As WWII came to an end, the world was getting divided between two victorious powers, the USA

and the USSR (United Soviet Socialist Republic) in Europe. Britain disappeared from the horizon

of superpower and the Indian Sub-Continent was divided into two independent states.

The geopolitical and geostrategic orientation of these two newly independent countries made a

drastic change soon after a year when Pakistan wanted to settle the most strategic piece of land,

Kashmir, with force. Both countries fought the first war over the Kashmir dispute a few weeks after independence in 1947 which ended under a truce brokered by the UN. As a result, Pakistan

gained one-third land of Jammu and Kashmir named Azad Kashmir, Gilgit Agency, and Baltistan.

On the other hand, India got two-thirds of Jammu and Kashmir with the rest of the Ladakh district

bordering China yet remaining disputed over the boundary line.

Be it as it may, the alteration and possession of part of Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan makes the border

dispute more complicated. As Joshi puts it, the border dispute between China and India, is ‘always

going to be a source of tension, and it certainly became one, since the Chinese do not agree to the

length of the border they claimed to be around 2000 km, the boundary for the area was always

going to be a source of tension, and it certainly became one, once other geopolitical interests

intruded’ (Joshi, 2022, p.3). The discrepancy ‘arises because the Chinese do not include the border

with Pakistan and then, their straight-line border in the foothills of Arunachal Pradesh (old NEFA:

North East Frontier Agencies24) helps make for the figure (Joshi; 2022; p45) (Chinese Claim).

For independent India, it was difficult to come out of the shoes of the British Raj. But it was India’s

first prime minister Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru who decided to go against his colleagues like K.M.

Panikkar, C, Rajagopalachari, T.T. Krishnamachari, and others. They were keen to see India

maintaining close ties with England in India’s geopolitical sphere. Their idea, much before India’s

independence, was that India took a pivotal role in Asian countries to start with keeping England

tied (Menon, 2021, p. 44). These strategic and geopolitical thinkers of India also saw a big role of

India dominating the Indian Ocean, particularly K.M. Panikkar echoeing Mahan with of course

the British Indian Navy (ibid, p.45) in mind. Panikkar did not stop there but wrote and advised

Nehru, “The Indian Ocean area together with Afghanistan, Sinkiang, and Tibet as outer northern

ring constitute the real security of India. Geographically also this is one strategic unit, with India

as its great air-land center and the base and arsenal of naval power. From the central triangle of

India, the whole area can be controlled and defended” (Panikkar, 1946, pp. 85-90 as quoted by

Menon).

Mr. Nehru was also forced and persuaded by others to form Indian defense and foreign policy

(ibid), much that is currently apparent. V.D. Savarkar who espoused Hindutva even pleaded with

the British Raj to keep the armed forces under British command by recruiting Hindu youth (The

Wire, 2022). But Nehru wanted an independent role for India, championing those Asian countries

that were yet to achieve independence and where the Indian-origin troops were present till then.

Nehru saw ‘India’s Independence as the rise of Asia’. He decided to maintain ‘strategic

sovereignty’ and keep India away from two superpowers, and to a great extent, he succeeded. The

idea that Mr. Nehru got, much before the ‘independence’ was from the ‘The Asian Relations

Conference’ in New Delhi held in March- April 1947, a few months before India declared

independence organized by the Asian Council of World Affair25. The conference, with the idea of gathering newly independent Afro-Asian countries together in the Indonesian city of Bandung in

1955, was Nehru’s idea who was a key organizer along with Mr. Sukarno, the president of the

newly independent Indonesia, and a few other countries including Pakistan. The Delhi conference

also gave birth to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in the 1950s in the aftermath of the Korean

War. Ultimately NAM was given shape in the Cairo conference in 1961. It was a great achievement

for India's geopolitical policy makers headed by Nehru.

India as its diplomacy in Asia first participated as peacekeepers in Korea in 1950 and Suez in

195626. Under British auspices, Indian-origin persons were settled all over the countries under

British colonial rule. India also raised its voice for their independence.

Sino-India-

27 Relations: 1959 - 1962. After the first Indo-Pak war in 1947-48, the bigger strategic

concern that upset the entire geopolitics of India was when China took control of Tibet in 1950.

By 1959, China was breathing on the Indian neck, bringing the Chinese boundary along a big

Indian track (Menon, 2021, p. 56). It was not only a setback for Indian foreign policy orientation

but a second geopolitical shift after the creation of Pakistan in India’s western and eastern flanks

as Olaf Caroe observed (Brobst, 2005, pp. 145-46). Nevertheless, after years of turmoil where

allegedly CIA-trained Tibetan guerrillas, with India’s covert knowledge28, and with the base

Provided by Nepal alongside the Tibet border, Mustang29 and in collusion with the then Pakistan

authority (in the then East Pakistan), involved in fomenting guerrilla resistance.

As for the involvement of the Government of Pakistan is an interesting episode in this fray with

India since both the countries had, by then, divergent geostrategic and political perspectives around

the Kashmir dispute. In this regard Riedel (2015), an ex-CIA officer, mentions in his book, "The

ISI arranged for them to stay briefly at an abandoned World War 2 airbase named Kurmitola

(Dhaka) .... the base was relatively primitive with a landing strip of 1,000 meters (sic) long,". He

further writes, "By October 1957, the first team of Tibetans was ready to go home and use their

newly developed skills to help the rebellion. Polish anti-communist emigres flew the B-17 bomber

and dropped the trained fighters in Tibet overflying Indian territory from Kurmitola again so that

no American would risk capture if anything went wrong...the mission was a success and the second

flight from East Pakistan followed in Nov 1957."30 Interesting to note both India and Pakistan were

colluding with the USA to stop the spread of Communism in the rest of Asia, but till the Chinese

occupation of Tibet, India was the closest friend of China and Mr. Nehru and Chinese Premier

Zhou Enlai were towering leaders of Afro-Asian countries and were regarded as the best of the friends. In India, both countries, India and China were known as Bhai-Bhai (brothers) with the

slogan ‘Hindi Chini Bhai-Bhai’(Rachenko,2014).31

Therefore, communism was perceived as a common threat to all these three countries, India,

Pakistan, and Nepal, that willingly got into the fight against communism which spread in Asia, in

particular. India stood clearly against the earlier stand of the ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ concept of

cooperation in the Asian region.

Tough India-Pakistan relation exacerbated soon after the partition on the dispute of Kashmir, but

on the hind side, Pakistan not only gained strategically important territory but also put a handicap

for India to maneuver easily on the west. In 1948, the Kashmir ceasefire brokered by the West and

implemented by the United Nations (UN) provided Pakistan a close link with the West, particularly

with the UK and the USA. In this regard, Dasgupta as quoted by Menon (2021) showed how power

politics was played by the UK and USA for a solution that went in favor of Pakistan. This favored

and put Pakistan willingly into the lap of the West. Though Pakistan had been at the Bandung

conference as one pioneer country and later a member of NAM, but did not maintain a ‘strategic

sovereignty’ like India. It allowed the USA to establish a base in Northern Pakistan to spy over

both China and mainly Russia32. But the fact remains that Pakistan’s geopolitics was and still is

around its big neighbor. Pakistan went pro-west and anti–communist even after General (later

Field Marshall) Ayub Khan took over the reign of Pakistan deposing the civilian government in a

military coup in 1958. That was the first-ever military takeover of a South Asian country. The

USA established a military relationship with Pakistan in the 1950s which continued till the 1965

Indo-Pak war.

Pakistan joined the Baghdad Pact in 1955 which later was known as the Central Treaty

Organisation (CENTO)33 as Pakistan had another part in the East as East Pakistan, almost

separating Indian North East from mainland India, and also justifiably joined the South Asia Treaty

Organisation (SEATO)34. This was another military pact aimed at providing Southeast Asia with

Collective Defence, almost concurrently that of CENTO. Thus, Pakistan was bound by these

alliances and could never maintain ‘Strategic Sovereignty’. Both these organizations were anti-

communist and were designed to stop the spread of communism almost at the beginning of the

Cold War as well as the spread of communist ideology, particularly in South Eastern Asia.

Pakistan remained a bulwark of the West against the spread of communism in South Asia.

Pakistan’s western-oriented geopolitics kept both the Soviet Union and China at bay though

Pakistan had an inaccessible yet disputed border with China during pre–Karakoram Highway days (KKH). China, however, never recognized Pakistan’s hold on Hunza and Gilgit in the North.

Therefore, China and the threat of communism remained a common factor for the newly

independent Sub-continent.

In 1949, Indian PM Mr. Nehru offered a ‘No war pact’ in a letter to the then Pakistani Prime

Minister Mr. Liaquat Ali Khan which remained inconclusive till 1950 (Ranjan, 1964, p.79). Even

in 1959, a month after Dalai Lama fled to India, he once again offered no-war pact and Pakistan

had not responded, as Mr. J.N.. Dixit (2002) wrote in his book, India-Pakistan in War and Peace’,

but Pakistan, then led by Ayub Khan, did not agree rather continued to assist the US to operate U2

spy planes from both wings against the Soviet Union and China.

The then CIA (Central Intelligence Agency), was continuing with clandestine operations against

China in Tibet, and the US U-2 spy missions continued regularly for spying over China. At the

same time, USA-trained Tibetan dissidents were regularly inducted from East Pakistan using the

vintage WWII Kurmitola airfield. Later Mustang, a remote mountain valley in Nepal, became the

anti-Chinese training base of Tibetan dissidents (Knaus, 1999; Conboy and Morrison, 2002,

Riedel, 2015). Though Pakistan and India did not have any pact as such but took some times active

and mostly passive parts in CIA operations until 1969 (Conboy and Morrison, 2002, p. 38)35. At

the height of the PLA (Peoples Liberation Army) operation in Tibet, the Chinese authority detected

the clandestine operation. The Chinese perceived Indian involvement and tacit approval of such a

clandestine operation.

Despite, the fact that India under Mr. Nehru had better relations with the Kennedy administration,

India became inclined to the USSR36 for military equipment. The USA tried to persuade Mr. Nehru

but the Western offer did not match the price. The Soviet Union gave India 12 MIG 21s free as a

friendly gesture. On August 17, 1962, a few months prior to Sino-Indian war, the Indo-Soviet

treaty37 was signed mainly for procuring defense equipment. Nehru was trying to counter the

USA’s supply of F-104 Star Fighter to Pakistan (Riedel, 2015, p.116). China was not happy that

the Soviet Union supplied hi-tech aircraft to a country that was not considered a friendly one to

them, particularly for interfering in Tibet. (op. cit, p. 99). These were viewed by the Chinese

violation of established relations through Panchsheel and ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai’ (India- China

Brothers) pact in 1954. These events led to a fast deterioration of the relationship between the two

Asian giants. The bitterness over Tibet, Dalai Lama, and dispute over the borders, both in India’s

north in Ladakh and North East in NEFA (North East Frontier Agencies)38 made worse enemies

of countries that once held similar views of anti-imperialism.

1962 Sino

-Indian War and Beyond that Changed the Geopolitics of the Sub-Continent

Prelude

The main causes for the deterioration of relations between two giant neighbours, India and China,

seemed to be (1) interference in Tibet by India. Like British India, Nehru considered Tibet a buffer

within the communist menace of China. In all analysis, Nehru seemed to have stepped into British

shoes of India even after 1947.

(2) The exodus of Dalai Lama to India and shelter given first at the disputed (As China claims)

largest Buddhist monastery of Tawang (NEFA: now a district of Arunachal) and then to

Dharamshala which brought huge international attention to Buddhist persecution by the

communist China.

(3) Border dispute which remains complicated, especially in Ladakh, Aksi-Chin area to the south

of Karakoram Range. The area was inaccessible and India had neither an updated map nor many

ideas of this high-altitude plateau unless China produced a map in which a road connection

between Tibet and Xinjiang through a military road was shown on the Chinese map as China did

not recognize ‘Jhonson Line’40 much to the North East Aksai-Chin. China rather accepted the

‘Macartney-Macdonald Line’41. India objected to the Chinese unilateral move but China claimed

that the area was shown on the map which was produced by the Nationalist government. This

position of China in Aksai Chin and the road built thereafter was not acceptable to Nehru and he

termed his stand as firm ‘not open to discussion with anybody’ (“Sino-Indian border dispute”,

n.d.).

Nehru was under further pressure as China also refused to accept the ‘McMohan Line’42 on the

North Eastern border up to Burma (now Myanmar). In 1954, the Chinese map showed Bhutan,

Nepal, Sikkim, and NEFA (now Arunachal) as part of China (Menon, 2021, p. 89). Chairman Mao

Zedong claimed these four areas including Ladakh are the five fingers of Tibet (“Five Fingers of

Tibet”, n,d.). China still maintains that stand whereas she is dealing with both Bhutan and Nepal

as sovereign countries43

.

(4) Last but not the least, the earlier China offered to settle the border dispute amicably earlier by

trading Aksai Chin against China recognizing the McMahon Line. The Indian government of Mr.

Nehru ruled out such compromise, rather quietly implemented a forward policy

through war.

(5) Forward Policy44 of Nehru. The policy was based on setting up military posts behind Chinese

lines, in disputed territory, to gather intelligence and compel China with a show of force. The

Indian troops were of no match in terms of armed forces equipped with insufficient appropriate

weapons, equipment for snowline warfare, and unclear orders (Riedel, 2015, pp. 99-100; Noorani,

1970, pp. 136-141; Jensen, 2012, pp. 55-70).

All these and other geopolitical factors became the primary reason for the 1962 Sino – Indian war

that changed the geopolitics of the region in particular and Asia in general. On November 20, 1962,

the Chinese declared a unilateral ceasefire. Researchers like Nevil Maxwell45 and Prem Shanker

Jha46 opine that it was the disastrous forward policy of Mr. Nehru that gave reasons to counter-

attack India.

In that short war, India lost with a humiliating defeat. Having learned a lesson, India could not

maintain regular surveillance of Chinese moves from November 1962 and created the Tibet

refugee-based Special Frontier Force (SFF)47 (Shukla, 2020) which is enlarged at present and used

to monitor behind the Line of Actual Control (LAC)48

.

The effect of the 1962 war and its disastrous consequences became the psyche for the Indian nation

and policymakers. The geopolitics of, not only India but also South Asia, Asia, and the world have

since been shifting as a result of the Sino-Indian War of 1962.

Two major events factored in changes in policies affecting South Asia to an extent, the

assassination of Kennedy in November 1963 and followed by the death of Nehru on May 27, 1964.

After Kennedy, India drifted away from the USA’s strategic partnership to counter China as the

Johnson administration was busy with internal consolidation (Paul, 2013, p. 280-84) but the Nehru

government was still dependent on US military support against China. The other event that

polarized South Asia was the Indo-Pak War in 1965.

About the Creator

Riham Rahman

Writer, History analyzer, South Asian geo-politics analyst, Bengali culture researcher

Aspiring writer and student with a deep curiosity for history, science, and South Asian geopolitics and Bengali culture.

Asp

Comments (2)

Great!

Wow! Great Research!