Serhii Gromov, Ukraine’s Peace Museum in Kyiv: UN Peacekeeping History, and the Žepa Legacy Amid War

Serhii Gromov: How does Ukraine’s Peace Museum in Kyiv preserve Serhii Gromov’s UN peacekeeping legacy while operating during Russia’s full-scale invasion?

By Scott Douglas Jacobsen and Milana Olefirenko Bennett (Translator English-Ukrainian)

Ukraine’s Peace Museum in Kyiv, founded by former UN peacekeeper Serhii Gromov, documents the country’s contributions to international peacekeeping missions since the early 1990s. Through personal archives, mission artifacts, flags, and correspondence, the museum highlights deployments in the former Yugoslavia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Angola, and beyond. A central narrative focuses on the 1995 Žepa operation, which Ukrainian accounts credit with saving thousands of civilians. Operating during Russia’s ongoing invasion, the museum presents a paradox: a peace institution functioning in wartime. Its mission is both archival and aspirational, asserting Ukraine’s identity as a peace-contributing nation while enduring active conflict.

The Peace Museum in Ukraine (“Музей Миру”) presents itself as a space for peace-building and civic education. A mausoleum for public reflection about building a peaceful society through exhibitions and outreach. A platform for peace education and for promoting Ukraine’s peacekeeping record.

The museum sits within the broader “museums for peace” ecosystem. It has been a member of the International Network of Museums for Peace (INMP) since July 7, 2022, according to the museum’s own website, which is part of an international community of peace-museum practice.

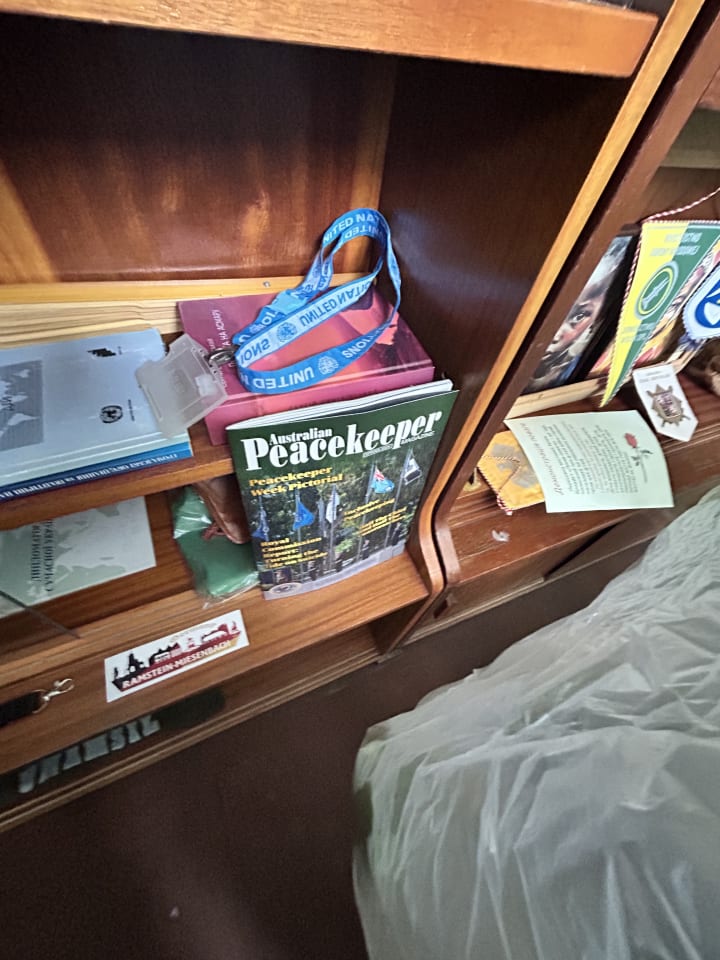

Serhii Gromov, who is the museum’s director and one of its founders, is a former Ukrainian peacekeeper. He was involved in Ukraine’s peacekeeping missions, including service connected to Sierra Leone/UNAMSIL (2003/04). In the museum space, one can find maps, patches, flags, letters, and mission artifacts as primary evidence to narrate peacekeeping work and international cooperation.

“I founded the Peace Museum on September 21, 2021, on the International Day of Peace in association with the Vasyl Yan Library in Kyiv. In 2024, I found this small room, and we decided to open the museum here,” Gromov said. “It is dedicated to peacekeeping cooperation, because this is very important for us. Many Ukrainian soldiers have served in peacekeeping missions.”

The museum’s story engine is inherently paradoxical. It foregrounds Ukraine’s peacekeeping past and peace-building identity while operating amid an invasion and wartime archiving. A Ukrainian peace museum explains peace through the vocabulary of survival.

Gromov framed the museum's work as documenting Ukrainian peacekeeping history through a personal, volunteer collection. I asked Gromov about the most meaningful exhibit in the museum.

He said, “For me, the most meaningful exhibit is this flag. It was given by a colonel who commanded a battalion that protected civilians in Žepa during the war in the former Yugoslavia. Another British colonel was deeply impressed by the conduct of the Ukrainian soldiers and presented this flag to him as a gift.” Žepa had 79 Ukrainian peacekeepers on nine APCs operating in 1995. Evacuation negotiations were central to these operations.

Gromov spent part of his career in peacekeeping activities in aviation and helipad operations, which means receiving helicopters and coordinating takeoffs. His retirement work is a continuation of the peacekeeping work. The memorabilia presented and discussed reference commanders, donors, friends, and international contacts throughout the time in the peacekeeping operations. Ukraine has been a contributor to UN peacekeeping since the early 1990s.

These include missions and geographies in the former Yugoslavia, the Balkans, Slavonia, Sarajevo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Angola: the former Yugoslavia and the Balkans with two battalions and a helicopter unit.

Sierra Leone had the discussion shift to the mission and multiple sub-units, e.g., battalion, repair engineers, and a helipad unit. Shirts, masks, and devices are shown from this period. The electricity is off for most of the day, so the museum room is cold, and the lighting is moderately dim in the late afternoon.

Items from Liberia include various mosquito repellents for malaria protection and items related to his profession in aviation. Angola shows a company. He had many Kenyan friends in Africa.

The core collections of the museum include an enormous number of memories of lives throughout the world in peacekeeping work: Anti-mosquito net, beret, coins, colonel’s archive (Ukrainian- and English-language documents), envelopes/mission mail, flags, letters (including one from a nurse in Yugoslavia), maps, memoirs, newspaper items, patches/emblems, pilot device, and T-shirts.

There is a provenance narrative. In that, many items are framed as gifts from visiting peacekeepers, foreign officers, and various mission contacts from Australia, Germany/Ramstein, Liberia, and the UK/Wales.

Gromov reflected on why these peace museums matter, “It matters because we hope the war will end soon. If foreign peacekeepers come to Ukraine, our history should be interesting and meaningful for them.”

One story, the Žepa story, is a moral center in the discussion about the museum’s contents and stories. Gromov treats this as a defining ethical narrative, where, from his framing, Ukrainian soldiers “did not allow” a massacre or a mass killing there. He ties this to the shadow of Srebrenica. Srebrenica was the killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in July 1995. Ukrainian summaries credit the Žepa episode with saving more than 10,000 civilians.

According to Gromov, no medals or official recognition were given for Ukrainians involved in the Žepa operation. He claims an attempt was recently made to raise it again with President Zelenskyy, with documentation.

The outreach from this newer, smaller museum is extended to international audiences as well. Gromov plans a small booklet about the museum and an exhibition of soldiers’ artwork called “trench art.”

On what they want to show about one side of Ukraine, Gromov opined, “We want to show that Ukraine is a peaceful country. We have done much for peace, and we hope that Europe, North America, and the rest of the world will help us restore peace in our country. We are tired of war. We dream of peace.”

Scott Douglas Jacobsen is a blogger on Vocal with over 120 posts on the platform. He is the publisher of In-Sight Publishing (ISBN: 978–1–0692343) and the Editor-in-Chief of In-Sight: Interviews (ISSN: 2369–6885). He writes for The Good Men Project, International Policy Digest (ISSN: 2332–9416), The Humanist (Print: ISSN 0018–7399; Online: ISSN 2163–3576), Basic Income Earth Network (UK Registered Charity 1177066), A Further Inquiry, The Washington Outsider, The Rabble, and The Washington Outsider, and other media. He is a member in good standing of numerous media associations/organizations.

Image Credit: Scott Douglas Jacobsen/Milana Olefirenko Bennett.

About the Creator

Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Scott Douglas Jacobsen is the publisher of In-Sight Publishing (ISBN: 978-1-0692343) and Editor-in-Chief of In-Sight: Interviews (ISSN: 2369-6885). He is a member in good standing of numerous media organizations.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.