Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Literary Voice

From stolen childhood to literary triumph the true story behind Wheatley’s rise from slavery to the heights of American letters

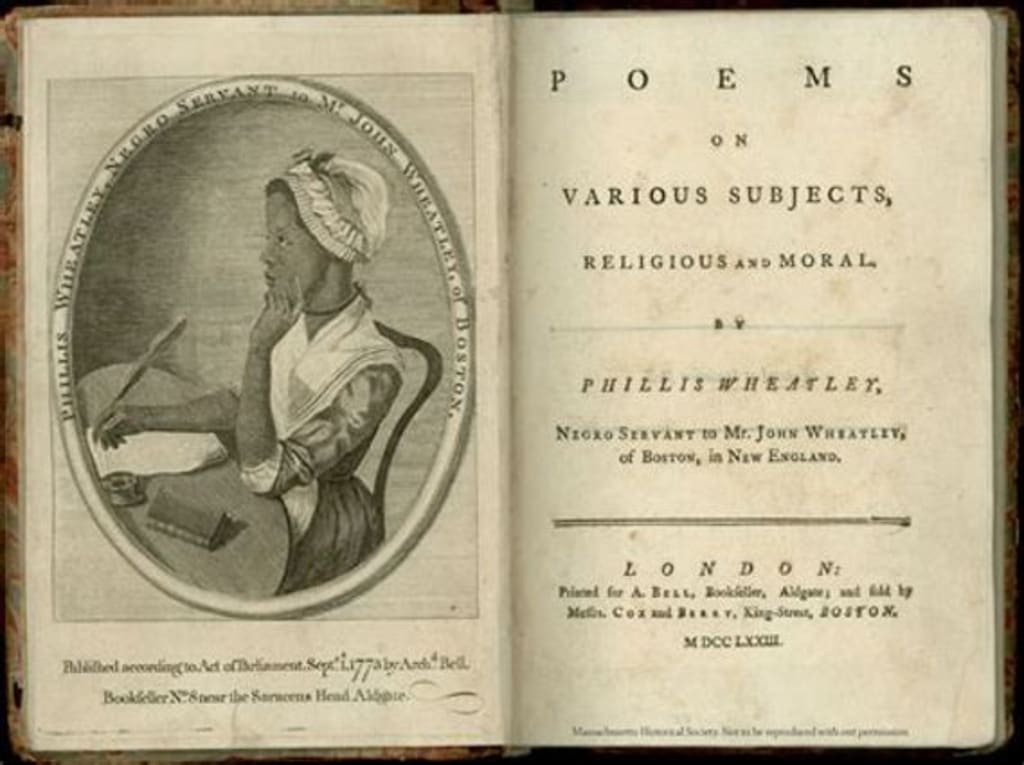

In the summer of 1773, a slim volume of poetry appeared in London under the title Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. The author was Phillis Wheatley, a young Black woman from Boston who had never known freedom. Her name alone stirred curiosity. Her words left an impression that has endured for centuries.

Phillis Wheatley’s life began in West Africa around 1753. At the age of seven, she was taken from her home, forced aboard a slave ship, and transported across the Atlantic. She arrived in Boston in 1761 and was sold to the Wheatley family. She was small, frail, and sickly. Her survival alone defied expectations.

The Wheatley family named her after the ship that carried her the Phillis. They soon noticed her intelligence and, in an unusual decision for enslavers, allowed her to learn alongside their children. Within sixteen months, she had mastered English. Soon after, she began reading Latin and Greek. She studied the Bible, astronomy, and classical literature. By her teenage years, Phillis Wheatley was writing verse that rivaled many educated poets of her time.

Her first known poem, To the University of Cambridge in New England, was written before she turned fifteen. Addressed to students at one of the most prestigious institutions in the colonies, the poem urges moral and spiritual responsibility. It speaks with both the humility of a believer and the confidence of a mind aware of its strength.

She writes:

“Students, to you ’tis given to scan the heights

Above, to traverse the ethereal plain,

And mark the systems of revolving worlds.”

These lines came from a girl born free in Africa, sold as property, and writing in a tongue not her own. Her message challenged the very structure that allowed her to be enslaved. She had no wealth, no liberty, and no standing in the world only the clarity of thought and the precision of her words.

Publishing a book in the 18th century required money and influence. As a Black enslaved teenager in colonial America, Wheatley had neither. Her supporters largely white elites in Boston failed to find a publisher in the colonies willing to print her poems. They turned to London, where she became something of a literary sensation. Her 1773 publication made her the first Black woman in America, and the first person of African descent in the colonies, to publish a book of literature.

Wheatley’s rise caused unease. Many questioned whether she had written her poems herself. In response, she was forced to defend her authorship before a panel of eighteen men, including John Hancock. Only after they verified her talents did her work reach print.

Her fame spread quickly. George Washington received a poem from her in 1775. He responded with praise, inviting her to visit him at his camp in Cambridge. Voltaire and other European intellectuals took note of her. For a brief moment, Wheatley’s name stood alongside the great minds of her age.

Despite this acclaim, she lived in near-constant isolation. Her status as an enslaved woman in a white household meant she occupied a space of silence. She had no peers, no real allies, and no family of her own. Her poetry reflected this solitude of elegies, spiritual reflections, and distant praises of liberty.

After her return from London, Phillis Wheatley was freed by the Wheatley family. Freedom, however, offered little security. She struggled to find patronage. Her second manuscript of poetry vanished without publication. Her former supporters faded away. She married a free Black man, John Peters. Their life together was marked by poverty and instability.

Wheatley gave birth to three children. All died in infancy. She worked as a laundress to survive, still writing poems no one would publish. On December 5, 1784, she died in a boarding house, alone and nearly forgotten, at approximately thirty-one years old. Her last surviving child died the same day.

The tragedy of Phillis Wheatley’s life lies not only in the hardships she endured but in how her brilliance was ignored once it no longer served the interests of the powerful. Her story reflects fleeting recognition and quiet erasure. Yet her voice never disappeared.

In her poems, the reader finds more than talent. They find defiance. She wrote during a time when literacy among enslaved people was feared. Expression was rebellion. Poetry, for her, became a means of reclaiming identity and asserting intellect in a society that denied her humanity.

Wheatley’s legacy today carries more weight than it did during her life. Schools teach her work. Scholars study her influence. Writers of all backgrounds cite her as a foundational figure. She stands as a symbol of what can be achieved in the face of oppression and as a reminder of how often greatness is overlooked when it doesn’t wear the expected face.

The solitude of Phillis Wheatley was not only personal. It was historical. She wrote alone, lived among strangers, and died unseen. Her words, however, survived. In them, she left behind not a cry for pity, but a call to witness. Her poems demand acknowledgment not only of her genius, but of the silence that surrounded it.

Phillis Wheatley wrote:

“In every human breast,

God has implanted a principle which we call Love of Freedom.”

That line, penned by an enslaved teenager in a colonial world built on bondage, rings louder today than it did two centuries ago. Her life, brief and full of obstacles, stands as one of the earliest chapters in the ongoing story of Black American literature. She was the first voice, a solitary one that still remains.

On Being Brought from Africa to America

by Phillis Wheatley

’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

About the Creator

Tim Carmichael

Tim is an Appalachian poet and cookbook author. He writes about rural life, family, and the places he grew up around. His poetry and essays have appeared in Bloodroot and Coal Dust, his latest book.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.