Parasite” – The Movie That Spoke the Truth We Were All Too Afraid to Say Out Loud

Movie Review

It begins in the shadows.

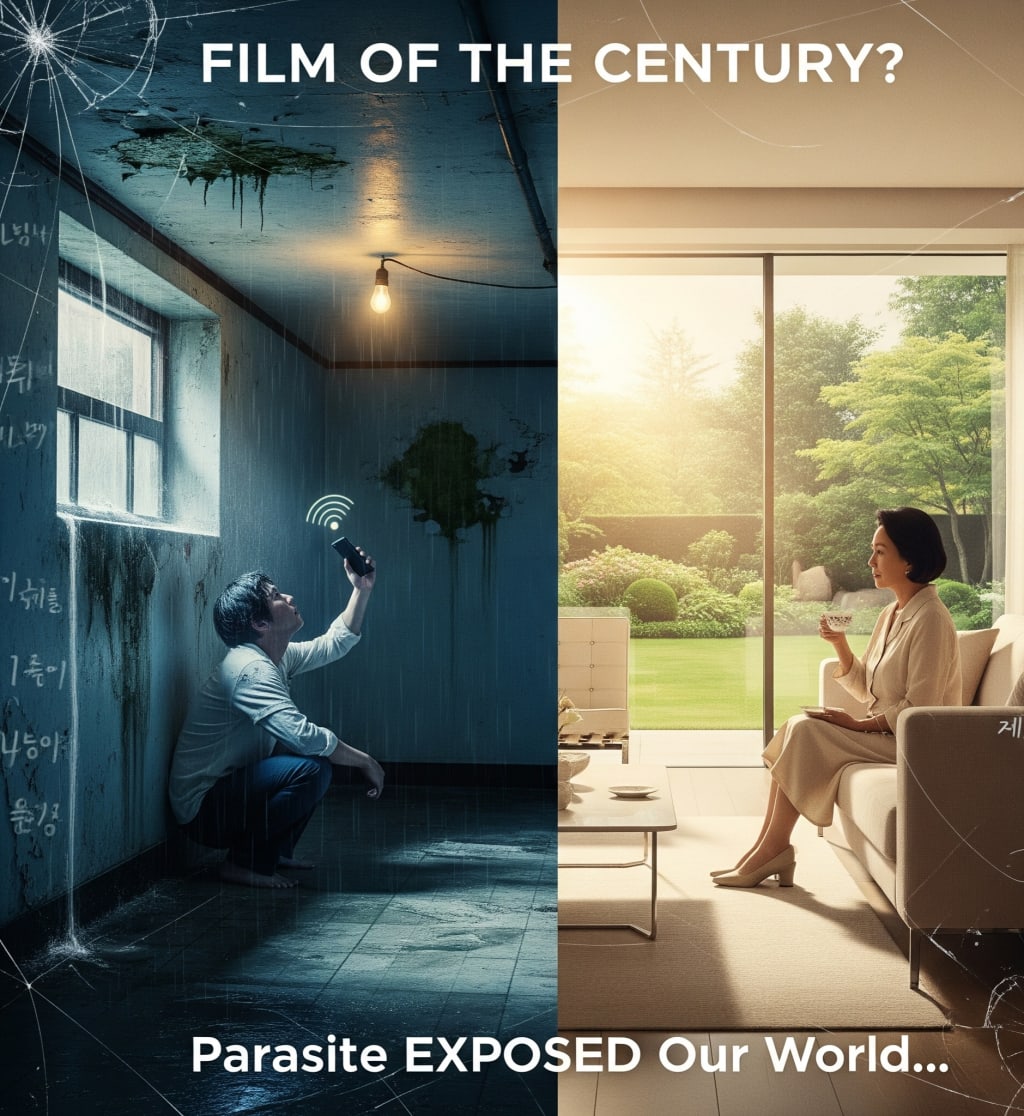

In a half-submerged basement, damp with the scent of mold and ramen steam, a boy holds his phone up to the ceiling trying to steal Wi-Fi. The light flickers like hope does in the hearts of people like him—people who survive not because the world allows them to, but because they find a way to smile when the world turns its back. His name is Ki-woo, and his family, the Kims, are neither lazy nor criminals—they are clever, like all the poor are forced to be. They fold pizza boxes for pennies, chase drunk men for jobs, and laugh in the dark to keep from crying.

But far above them—almost in another world entirely—a family named Park lives in a modern architectural wonder. Their walls are made of glass, but somehow they see nothing. Their fridge is always full. Their worries are fashionable. Their house is beautiful, with manicured lawns and filtered sunlight, and the silence that money buys. If the Kim home is survival, the Park home is fantasy.

And then—Ki-woo gets an opportunity. A friend offers him a tutoring job with the Park family. Just like that, the basement door creaks open. He gets a fake degree, puts on his cleanest shirt, and walks up the hill—not just literally, but socially. That climb becomes the film’s beating metaphor. And as Ki-woo enters the Park home for the first time, he doesn’t just step inside a house—he walks into a dream. A world so clean, so effortless, so beautifully stupid that it feels like heaven. And like all forbidden fruit, once tasted, it becomes irresistible.

The story from here could have been simple. But Parasite doesn’t deal in simplicity. It unwraps like a magic trick—a con layered inside a con, until you realize the real con is the world itself.

One by one, the Kims infiltrate the Park family. The sister becomes the art therapist, the father the chauffeur, the mother the housekeeper. They remove the existing staff like chess pieces, not with cruelty, but with strategy. It’s brilliant. It’s funny. It’s wrong. And yet—we root for them, because they are us. Because we’ve all wanted a shortcut out of the hole we were born into. Because we’ve all been told that success is just a matter of trying hard enough, when in truth, the ladder isn’t even in our hands.

The Kims play their roles so well that even the Parks—who seem smart and composed—don’t see what’s happening. But it’s not about intelligence. It’s about distance. The Parks are so removed from reality that even when the basement smells of poverty, they can’t name the scent. They just wrinkle their noses and open a window.

And then comes the rain.

Not just a drizzle. A flood. A Biblical deluge that brings everything to the surface—secrets, smells, truths. On the night of a perfectly orchestrated lie, the Parks come home early from a trip. The Kims scramble like insects under sudden light. What happens next is not comedy. It’s chaos. They discover a hidden basement under the house—one that even the Parks don’t know exists. And in it, a man. Pale. Starving. Worshipping the man of the house like a god, turning on light switches as a form of silent devotion. It’s a terrifying moment—not because it’s supernatural, but because it’s real. Because somewhere, right now, someone lives like this.

And in this moment, the truth snaps into place: The house is a parasite, too. Beautiful on the outside. But below, it festers with rot, with desperation, with the forgotten. The Parks live upstairs. The ghosts live downstairs. That’s the system. That’s always been the system.

The rain doesn’t just disrupt—it divides. While the Parks sip wine and celebrate their son's birthday the next day, the Kims wade through sewage back to their flooded apartment. They sleep in a gymnasium with strangers who’ve lost everything. Their dream drowned in feces and dirty water. But the next morning, Ki-woo puts on a smile. Because the show must go on. Because poor people are taught to suffer quietly.

Then, during a party that’s supposed to be cheerful, something happens. Something irreparable. In the sunlight, with laughter all around, a knife appears. And with it, rage. Not the rage of a killer, but the rage of a man who’s been stepped on too many times. When Mr. Park pinches his nose in disgust—reacting not to blood, but to the smell of poverty—Mr. Kim snaps. And in that moment, we all understand. It isn’t personal. It’s existential. That smell, that invisible barrier that separates rich from poor—it kills more than any weapon ever could.

The aftermath is silent. Cold. Bleak.

Ki-woo survives the incident but with a scar on his skull and his soul. His father disappears into the bunker. The dream shatters like a mirror, and what remains is just memory—and a plan. Ki-woo promises himself that he’ll make money. He’ll buy the house. He’ll free his father. He imagines it all happening in a perfect sequence, like a montage. And for a moment, we believe it too. Until Bong Joon-ho, in his final cruelty, shows us the truth: It was just a fantasy. Just another illusion. Another invisible ceiling.

What makes Parasite so powerful is not that it tells a good story—it tells our story. It tells the story of every invisible worker who smiles through pain. Every delivery man who opens the door to luxury and knows he can never afford to sit inside. Every person who changes their accent in a job interview. Every mother who skips meals so her children can eat. Every father who dreams of dignity, only to be treated like furniture.

This isn’t just a Korean story. It’s a global one. It’s the story of New York Uber drivers, of Mumbai slumdogs, of London’s invisible immigrants, of Johannesburg’s forgotten workers. It’s a reminder that we all live in the same city, but on different floors. That some people look out their window and see the sun, while others only see pipes.

Bong Joon-ho didn’t make a film—he broke a mirror, and forced us to look at the pieces. He created a world so specific and yet so universal that language became irrelevant. People didn’t watch Parasite. They experienced it. They left theaters in silence, in awe, in discomfort.

It became the first non-English language film to win Best Picture at the Oscars. It swept awards not just because it was flawless—but because it was fearless. It dared to say what most movies won’t: that capitalism isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed—but only for the ones who live upstairs.

The genius of Parasite lies not just in what it shows, but in what it makes you feel. It doesn’t scream. It whispers. It doesn’t accuse. It reveals. The metaphor is in the architecture. In the stairs. In the smell. In the rain. In the dream that was never yours to begin with.

Even the title—Parasite—is a double-edged sword. Who is the parasite? The poor who live off the rich? Or the rich who feed on the labor and suffering of the poor? The answer, perhaps, is both. Or neither. Or worse—it’s us, the audience, consuming it all, feeling moved, then going back to our lives as if nothing changed.

But something does change.

Once you’ve seen the basement, you can’t unsee it. Once you’ve smelled the lie, you can’t pretend it’s perfume. Once you’ve watched Parasite, the world feels a little less fair. A little less innocent. A little less yours.

And maybe, that’s the point.

Maybe the purpose of art is not to comfort, but to confront. Not to lull us into sleep, but to shake us awake. In that sense, Parasite is not just a movie. It’s a mirror held to our faces, showing us the shadows we live in, the masks we wear, the truths we bury.

It is a story without heroes. Without villains. Only people. Desperate. Dreaming. Drowning in systems too large to name. And for once, someone told their story without apology.

That is why Parasite is not just the film of the year, or the decade.

It is the film of the century.

About the Creator

Shakespeare Jr

Welcome to My Realm of Love, Romance, and Enchantment!

Greetings, dear reader! I am Shakespeare Jr—a storyteller with a heart full of passion and a pen dipped in dreams.

Yours in ink and imagination,

Shakespeare Jr

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.