Introduction:

There is an island in Andaman where nobody is permitted to go. However, it is officially a part of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, considering their intentions to be left untouched by the modern world it is being guarded by the government. It is being safeguarded by the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Act of 1956. Based on the 2011 census and based on the people who visited this place till today, sums up that they might be anywhere from 80-150 in number. They are self- sufficient in their living, which indicates they govern and lead a life according to their regulations.

The traditions and customs of these people are a mystery; no one can understand the language these people speak.

No one knows what they consider themselves or the reason they revolt back when outsiders try to go to their Island.

They located 36 kilometers left to the South Andaman Island named Wandoor. The noticeable neighbors of this mysterious Island are Port Blair, Counterpart South Sentinel Island.

Amidst of vibrant coral reefs and humongous natural beauty, painted skies and every ending ocean surrounding on all the sides. This place is eye candy for nature lovers.

Dense forest, which its house, is the icing on the cake to its mystery. This Island is home for the tribe called Sentinelese. According to the information, there were 18- 20 huts which were observed by the visitors to date.

As described by sources, it was noted that the support made the houses of tree branches, also mentioned that huts don't have any windows or stored things. People here barely wear any clothes, far from modern civilization away in the dense forest on their own, these people are self-sufficient in their lifestyle. They mostly depend on the natural products available in the wood like coconut, tortoises.

Inhabitants of this Island will never back off without hurting or killing any outsider if they enter their island perimeter after their warning. This improbable Island exists as it does from the first settlements of the Andaman Islands, a part of India which limits to only papers. It is infamously known as "The hardest spot to visit in the world".

The existence of this mysterious Island first came to limelight when British Surveyor John Ritchie who was passing by in a Survey vessel observed an array of lights along the seashore in early 1700. This was the first noted incident where it was understood that some people habit the Island. Luckily the vessel didn't stop near the Island; it just passed from the place after they saw the lights. It was the necessary information which stood until the late 1800s.

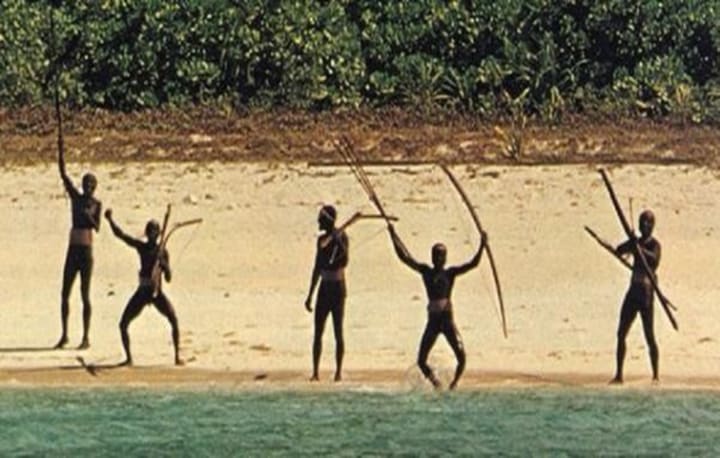

"Officer in charge of the Andamanese" named Jeremiah Homfray travelled to north Sentinel Island holding the trails of some escaped convicts of "Penal colony of Port Blair". After reaching the Island, Jeremiah observed nearly ten naked men along the beach, loose long hair, and dark in complexion who resembled troglodytes as they had arrows and bows in their defense. So, on the advice of the local Andamanese Jeremiah didn't enter the Island on that day.

HISTORY

It was believed that these people might have descended from the prominent populaces of Africa, and the theory suggests that these people were living in Andaman for as long as 60,000 years. The deduction which can be made from the language they speak is that they had no contact with the outside world, they don't share any similarities in customs, communication even with their neighboring tribes in islands. The Sentinelese are accepted to have lived on their island home for a long time.

Don't prejudge them because of their detachment from the modern world, these tribe who is often compared with stone-age people, indeed, know how to employ various instruments and weapons from the destroyed boats and metals on the shoreline. By observation, one can say that these people enjoy a very healthy and robust body. The only drawback is that as they are far from the medication, they are less immune from the diseases.

They might have habited the Island for a long time by now. Still, no one knows the precise dates of the transition of movement of them as compared to many other similar tribes, this particular tribe is known for the violent reactions to outsiders which gave them the title called "savage tribe". Their protective nature towards the Island and its people start with slightly uncomfortable tension when they see an outsider on their beach shore.

The small group of people trying to guard their homeland against any outsider furiously shows us the significant importance they have towards their Island. Theories suggest that these people might have to lead a

The lifestyle of seekers and gatherers from an extended period.

The chances are that these people might be the significant established group of tribal who hold rich information about the ancestral customs, their social life, and their so- called secret lifestyles. The scope of research and learning is dominant in this case as everything which we know or assume to know about them is purely based on the power of observation, no sort of proper communication has been made as the language hindrance stands tall among them and us.

NOTABLE LEGENDS AND WRITINGS ABOUT THE ISLANDS

"The earliest written reference to these islands is found in a literary work of an Indian poet who related how once Emperor Ashoka the Great was approached by some Indian Merchants who complained to him of their losses and complete ruin brought out by 'Black Savages' when they passed through the islands, in 3rd century BC."

"Ptolemy the Greek geographer who lived in second century AD called Andaman’s as Bazakata, got from the Sanskrit vivasakrata, signifying "deprived of garments". Old palm leaf Tamil engravings of Thanjavur allude to Andaman Islands as Theemai-t-the vagal (Islands of Harm or Evil)."

These are the lines which can be seen in many published journals and documents of history in the segment of the Andaman Islands and the whole tribe living in it.

WAY OF LIFE

Based upon the visual understanding of TN Pandit, who is the prominent anthropologist who provided the basic perception of the whole tribe of the world. It was he who entered the disconnected Andaman island of North Sentinel, in 1967 and leapt significantly in the information about them.

Pandit portrayed them a gathering of cabins, living in small tree huts with no windows, with a cautiously tended flame outside everyone. They have the skill set to make floatable platforms which resemble the kayaks in these days. They use the things to go to quiet waters and do fishing and gathering of crabs as their food.

As mentioned above, they are seekers and gatherers, if their way of life resembles any neighboring tribal groups that will be their dependency on the live products of nature such as eggs of seagulls, small grown pigs and beach turtles which is a part of their staple diet regimen.

They welcome their uninvited guests by a sky filled with arrows, showering the people visiting the place. Many hand instruments like spheres and sharp iron blades attached to long sticks, these are the standard defense weapons and mechanisms employed by the sentinel tribe.

These people know who to weave baskets from the natural products, and the making of long weapons with sharp pointed ends. Many ongoing travelers of the ocean informed about the indirect lighting along the shoreline during the evening accompanied with the singing, which tells us these people are not new to fire. However, there is still a dilemma about their knowledge of producing light.

Be that as it may, even today, no other person can understand the Sentinelese language apart from their tribe people, not even the famous anthropologists were able to understand and decode the language used by them. Their self-knowledge about their existence is still a significant doubt; what they call themselves is not known even today.

We can visibly understand whatever they do for a living or existence their way of welcoming the outsider and treatments available to them clearly shows their deficit in interest to connect with the modern world. At least this much was evident in their actions even though their language is not known, the messages sent was pretty clear.

INITIATIVES TO CONTACT

For many years they were left significantly undisturbed, as rumors about the existence of cannibalism in the Island.

The 1880'S

In 1880 a group of British invaders set their foot on this land. Under the leadership of colonial Administrator Maurice Vidal Portman who searched for the traces of tribal in every nook and corner of the Island. They intersected an old couple and some children. Covering it under the dark umbrella called "friendliness", the invaders transported the family to Port Blair. Very soon, the elderly couple passed away, due to sane reason that their bodies were not immune to diseases. Realizing the matter at hand, the invaders dropped the young kids back to the Island with lots of gifts.

After many observations made by various sources from an extended period, Indian anthropologist Trilok Nath Pandit provided prominent information.

He was appointed by the governor of Andaman Islands to head the planning expedition to this Island. So officially he was the first anthropologist to visit the sentinel island. He was accompanied with two boats full of naval officers after he took the role of manager of the expeditions titled "Contact Expeditions" under the tutelage of the director of Tribal Welfare.

There was a feeling that we were trying to establish friendly contact, which would be considered an achievement at the government level," Pandit said commenting on the overall effort of government in taking such initiatives.

One the first day of their visit, the tribe beat a retreat and went inside the jungle, hence no contact was made on this day. The so-called "contact expedition" left the shore with dropping buckets, coconuts, and some candies. In return, they swapped painted skulls of animals and handmade bows and arrows.

19970's

Again, on 29th March 1970, TN Pandit and his team arrived at the shoreline of the Island. According to the eyewitness, a chain of peculiar occurrences has happened.

"We were about to return when a couple of natives were seen on the land, apparently keeping a vigil.

We approached closer, keeping a safe distance from the shore, when more men came out of cover armed with their usual weapons, threatening to shoot at us.

We had taken a few large fish caught during the previous night to offer as an appeasement gift to these people. We exhibited these, with gestures of the offering.

Meanwhile, men were converging on the spot from all direction. Some were waist-deep in water and threatening to shoot. However, we approached closer and threw a couple of fish towards them. They fell short of them and were being carried away by the water.

This gesture had a mellowing effect on their belligerent mood. Quite a few discarded their weapons and gestured to us to throw the fish.

The women came out of the shade to watch our antics. In their height and stature, they were equal to the men except that the lines were softer and they carried no arms

… There were 20 children. We approached the coast a little further from them and managed to land a couple of fish onshore. A few men came and picked up the fish.

They appeared to be gratified, but there did not seem to be much softening to their hostile attitude.

Again, we approached the group. They all began shouting some incomprehensible words. We shouted back and gestured to indicate that we wanted to be friends. The tension did not ease.

At this moment, a strange thing happened – a woman paired off with a warrior and sat on the sand in a passionate embrace. This act was being repeated by other women, each claiming a warrior for herself, a sort of community mating, as it were. Thus did the militant group diminish? This continued for quite some time, and when the tempo of this frenzied dance of desire abated, the couples retired into the shade of the jungle.

However, some warriors were still on guard. We got close to the shore and threw some more fish which were immediately retrieved by a few youngsters. It was well past noon, and we headed back to the ship."

1991's

In 1991 when TN Pandit along with his team, went to the Island, something unusual happened. Rather than spearing the intruders with bows and arrows, the island people came unarmed to their boats to wish them; some even climbed up into the ships. They were observing and trying to touch everything. This was so far pleasant interaction with the sentinel tribe.

1996's

In the year 1996, post the widespread disease for which their bodies were not immune resulted in mass deaths of the tribe. This worked as an eye-opener as the case was similar to that of Jarawa’s, another tribe in Andaman. So, the government restricted expeditions to this island in late 1996s.

2006's

Until recently 2006 there was no significant news about this place, but the death of two fishers who went searching for mud crabs unknowingly crossed the proximity of the island. Arrows continuously shot the chopper which was sent to bring back the bodies.

PROTECTORS OF THEIR LAND

From the very beginning, it was very evident that they are unwelcoming or ready to establish a relationship with modern society. There might be many reasons behind this perception of them.

One of the prime theories is their belief in their self- sustaining ecosystem; they are happy with their lives on the island. They are getting all their needs satisfied by the island and nearby resources. It is visible that they are pretty much on their own from the very beginning, which gives us the information that they are not ready to accept the friendship or the so-called contact with the outside world because they don't need and primly they are not fond of those kinds of things for all this long.

We can speculate many theories which might be the possible factors for their disinterest in contacting the outer world. The prominent reason might be the way they were treated by the invaders from a very long time. There were instances where some of the tribes were kidnapped and transferred to Port Blair, which happened under the name of the establishment of friendship. Some people even died of the diseases which they got after contacting with the people from outside.

Their violent habit of spearing of people who enter the island proximity is probably the result of the factors mentioned above, which have made a long-lasting memory in their tribe.

For example, in the year 1858, according to the information provided by the British, the tribe population was close to 5000, which dwindled to 460 in the year 1931. It is the influence of alcohol, tobacco and mainly diseases which they got from the outside people.

Though many rumors say that the tribe is concealing something from the outside world, be that as it may, it very well understands why this is called a story.

But many anthropologists feel that we in the whole process knowing about them and their way of living, they will be facing against the substantial probability of their culture being destroyed in the entire process. That too a tribe which is unscathed by the modern world for many years.

The whole stage of getting to know them may end up in destroying their culture and may even end up their existence as they are very less immune to diseases. So, they are also facing chances of extinction in coming years if no proper actions are taken.

Indian kings Influence

During the period of Raja raja Cholan, some of the local kings made Andaman and Sentinel Island as their war base. There were no significant pieces of evidence to show the relation they had or the way they interacted with each other. They are rumors that the kings captured these tribes and trained them to use weapons and attack the enemies with their bows and arrows.

Incident of John Allen Chau

Chau, 26, was killed at some point between the evening of 16 November and the next morning, when fishermen who he had paid to carry him to the island state observed his body being hauled over the sand and covered.

The Sentinelese, whose clan is believed to be somewhere around 30,000 years of age, have forcefully opposed contact with outcasts for ages.

As indicated by Chau's journals, which he provided for the anglers before withdrawing for the island the last time, the American needed to "announce Jesus" to the Sentinelese, whose home structures some portion of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, an Indian domain dissipated over the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

An examination is formally proceeding against the seven men blamed for aiding Chau to reach the island.

Words by the Man himself before getting killed

"I heard the whoops and shouts from the hunt,"

As written by his own words after approaching the island on social outlets.

"I made sure to stay out of arrow range, but unfortunately that meant I was also out of good hearing range." this was sentence said by Chau himself.

"So, I got a little closer as they (about six from what I could see) yelled at me, I tried to parrot their words back to them. They burst out laughing most of the time, so they probably were saying bad words or insulting me."

"I hollered: 'My name is John, I love you, and Jesus loves you.' I regret I began to panic slightly as I saw them string arrows in their bows. I picked up the fish and threw it towards them. They kept coming.

"I paddled like I never have in my life back to the boat. I felt some fear but mainly was disappointed. They didn't accept me right away."

One among the tribe on the shore– "a kid probably about ten or so years old, maybe a teenager" – shot an arrow that pierced through his Bible, he wrote that night, on board the boat of fishermen he paid 25,000 rupees (£275) to transport him to the island. "Well, I've been shot by the Sentinelese."

Following the day after, Chau sent a letter his parents expressing his thoughts about his action "You guys might think I'm crazy in all this, but I think it's worth it to declare Jesus to these people,"

"Please do not be angry at them or God if I get killed. Instead, please live your lives in obedience to whatever he has called you to, and I'll see you again when you pass through the veil.

"This is not a pointless thing. The eternal lives of this tribe are at hand, and I can't wait to see them around the throne of God worshipping in their language, as Revelations 7:9- 10 states."

His last words to the world are: "Soli Deo Gloria" (glory to God alone).

Status of sentinel Island now

Recently in the year, 2018 government of India relaxed the Restricted Area Permit (RAP)

For the 29 islands which include North Sentinel from 2018-2022. However, they realized the danger revolving the island, so the government's home ministry amended as to allow only researchers and academic anthropologists along with the preapproved permissions before visiting the Sentinel Islands.

Three myths about North Sentinel Island

The recent killing of an American by a North Sentinel tribe has put the isolated island on the map. But there are three myths about the North Sentinelese that have been regurgitated in media. Scott Hamilton sheds some light.

It was a story from another century. A young man landed on a small island, with a Bible in his hand. Men emerged from trees at the edge of the beach. Their skin was dark, unclothed. The missionary greeted them in English; they replied with arrows. Twice the apostle retreated to a ship beyond the island’s reef. His third visit to the island was his last. The heathens buried him in the beach where he had hailed them.

The recent death of John Chau has made North Sentinel Island famous. Journalists and commentators around the world have been busy explaining that the island is part of the Andaman’s archipelago, that its inhabitants are hostile to call interlopers, and that the Indian government, which has administered the Andaman’s since the British departed in 1947, has forbidden all contact with them.

But there are three myths about the North Sentinelese that have been regurgitated, in article after article. Here in the South Pacific, we’re in an excellent position to lance these myths. After all, the same sort of misconceptions was once aimed at the indigenous peoples of our region. Contemporary Pacific scholars can help us see the North Sentinelese in a brighter light.

The myth of unprovoked hostility

Many journalists and commentators have interpreted the slaying of Chau as the work of an aggressive and xenophobic culture. But the Sentinelese have good reason to distrust outsiders.

In 1880, the British colonial administrator Maurice Portman led an armed expedition to North Sentinel. Portman was a pedophile and a pederast who was obsessed with the bodies of young Andamanese men. By 1880, he’d already led raids on several islands in the archipelago and taken away children and adolescents to photograph and molest.

Some of Portman’s pornography survives: his photos show black bodies decorated by

Jewelry the colonist had imported from Europe. The Sentinelese fled before Portman’s force, but he was able to capture and remove to Port Blair four children and two elderly islanders. The pair of old people died quickly, but the children endured weeks in

Portman’s ‘care’ before being returned to North Sentinel.

It’s unsurprising that after the raid of 1880, the Sentinelese resisted visitors to their island. In 1896, a convict escaped from the prison at Port Blair and was washed ashore at North Sentinel. A search party found him on the beach with his throat cut. An anthropologist who came calling in 1974 got an arrow in his leg.

Indian authorities have declared an exclusion zone around North Sentinel, but fishermen-poachers persist in entering that zone. When Sentinelese shout protests from their beach, or approach in canoes, the fishermen often shoot. In 2006, two drunken Indian poachers fell asleep off North Sentinel Island. Their anchor broke; their boat drifted ashore. The Sentinelese strangled and buried them.

John Chau may have had peaceful intentions when he approached North Sentinel

Island, but his mere presence on the island could’ve been devastating. When he climbed into a kayak and paddled through North Sentinel’s reef, Chau made his craft into a rocket, and himself into its warhead. Chau was a healthy young man, but like anyone from the West, he was loaded with pathogens that could swiftly kill the Sentinelese who lack our immunity to a slew of diseases. When they killed Chau, the Islanders were neutralizing a biological weapon.

A look at the modern history of the other indigenous peoples of the Andaman’s suggests that the Sentinelese have been wise to isolate themselves.

Anthropologists believe there were at least 5,000 Andamanese when the British arrived in 1789. Today, there are less than 700. The Great Andamanese, who was once the

Archipelago’s most populous people, today number about 30 and live on a small reservation island in concrete houses. They no longer speak their language fluently but instead, communicate in an Andamanese-Hindu pidgin.

Most of them are alcoholics; many also have diabetes. The Onge people live in another, larger reservation and number about 100.

The Jarawa people live in the jungle of South Andaman Island. For centuries they refused all friendly contact with outsiders, preferring to shoot arrows at intruders on their land and to raid the villages on the edge of the forest. In 1996, a Jarawa teenager named Enmei fell out of a fruit tree he’d been robbing in the Indian town of Kalamata And broke his leg. Enmei spent six months in the hospital at Port Blair, the capital of the Andaman’s, where he learned to wear clothes and enjoy television. He went home as an emissary for the Indian authorities and soon persuaded his fellow Jarawa to make peace with the settlers.

Today, a road runs through Jarawa territory; tourists drive it with their windows down and cameras ready, like visitors to a safari park. Survival International, a London- based charity that advocates for isolated indigenous peoples, has published photographs and videos that show Jarawa dancing beside parked vehicles, in return for bananas and other food. Poachers infiltrate the Jarawa’s domain; they take away timber and bushmeat and leave alcohol and venereal diseases.

The myth of ancient isolation

Journalists have correctly noted that the North Sentinelese have in modern times Rejected outsiders. Too often, though, they’ve assumed that the Sentinelese have been isolating themselves for tens of thousands of years.

Like other ‘negrito’ peoples of Southeast Asia, from Sri Lanka’s Veddahs to Malaysia’s Semang, Sentinelese is descended from some of the first humans to leave Africa. The ancestors of the Sentinelese walked across what’s now the Bay of Bengal when an Ice Age had created a land bridge.

When seas rose, many of the early arrivals from Africa were left on small islands. It’s likely that, as the media has reported, the Sentinelese have lived on their island for tens of thousands of years. But that doesn’t mean they’ve been isolated all that time.

I recently discussed the Sentinelese with Dr Lorenz Gonschor, a German-born Pacific- resident scholar who’s an expert on indigenous resistance to Christianization. Gonchar pointed out that the Sentinelese, like other Andaman’s peoples, developed aqua technology long ago.

A quick look at a map should’ve shown the world’s journalists that North Sentinel Island is less than 40 km from the giant South Andaman Island and less than 60 km from South Sentinel Island. As Lorenz Gonschor pointed out, those are tiny distances for an island people. Gonchar argues that, rather than being isolated, the Sentinelese visited other Andamanese peoples. Their isolation wasn’t ancient, he thinks, but the product of British and Japanese colonialism, and in particular, the British invasion of the island in 1880.

We can use Lana Lopesi’s new book False Divides to understand what the North Sentinelese have suffered. Lopesi laments the way that, in the Pacific as well as the Indian Oceans, colonization interrupted histories of inter-island voyaging, trade and marriage. ‘Random lines’ were drawn on maps by ‘land-centric’ cultures, dividing the

Peoples of a vast liquid continent into ‘small colonies and resource bases. In many parts of the ocean, Lopesi calls Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa, colonial administrators banned inter- island voyaging.

Lopesi’s arguments float on an ocean of data. It’s 20 years since Lisa Matisoo-Smith’s pioneering DNA studies of rat bones showed that archipelagoes like the Cooks, Hawai’i and Tonga were visited again and again by different groups of Polynesians. Mattison- Smith’s findings were reinforced by an Australian study that found Tongan adzes (a cutting tool) on islands across the Western Pacific. The linguist William Watson has heard Hawai’ian words on atolls many thousands of kilometers from the Sandwich Islands.

The peoples of the Indian Ocean were as mobile as their Pacific cousins. The Indonesian scholar Waruno Mahdi has shown how Austronesian ships sailed west from his homeland to India, Madagascar, the east coast of Africa, and even the Red Sea. Mahdi has discovered Austronesian place names in Iraq, as well as the Indian Ocean, touches on Phoenician ships. Mahdi emphasizes that the negrito peoples, as well as the latecomer Austronesians, were sailors and navigators. He credits Negritos with the creation of the first outrigger canoes. Photographs in British museums support Mahdi: they show Andamanese hollowing tree trunks, attaching floats to them, raising sails.

There are some parts of the world where peoples have suffered radical isolation. The indigenous people of Tasmania, for example, were cut off from the rest of the world for about 12,000 years after an Ice Age land bridge vanished. But the isolation of the Sentinelese is a modern, relatively recent phenomenon.

The myth of a static culture

British journalist Brendan O’Neill has responded to the death of John Chau by arguing that the Sentinelese need to be ‘civilized’ so that they can experience the wonders of the West. O’Neill says that groups like Survival International, which campaign against forced contact with peoples like the Sentinelese, have forgotten the delights of modernity and learning and the misery of life in the forest.

Like many other commentators, O’Neill characterizes the Sentinelese as suffering from a frozen culture, a culture incapable of innovation. Similar claims have been made in the past for numerous other indigenous peoples by outsiders advocating colonial projects.

The late John Chau wasn’t much of an anthropologist. Still, one of the notes he scribbled before his demise included a fascinating detail that refutes claims Sentinelese culture is incapable of innovation. Chau described how an arrow with a metal head came flying his way. The metal on the Sentinelese arrow may well have come from the Primrose, a cargo ship that was wrecked on a reef off North Sentinel in 1981. The Primrose’s crew were rescued by chopper before Sentinelese could storm their vessel.

The Sentinelese have brought themselves into the Iron Age, by adapting metal from the Primrose for use on arrows and, in all likelihood, other tools. The material of his Civilization probably killed John Chau after an innovative island people had repurposed it.

In another note he made off the coast of North Sentinel, John Chau called the island ‘Satan’s last stronghold’, presumably because of its people’s resistance to Christianization. As Lorenz Gonschor points out, though, there are other islands where Christianity has been scorned, even in recent times. Most of the Polynesian people of Takutu, an atoll north of Bougainville, still prefer old gods like Tangaroa and Maui to Jehovah.

The ethnomusicologist Richard Moyle landed Takutu in the 1990s and was able to record scores of religious songs and chants and sacred video events like seances. Moyle’s words and footage are a door to ancient Polynesia, before the intervention of missionaries and colonial administrators (many of Takutu’s inhabitants have emigrated in recent years, as the seas around the island rise; it’s unclear whether their religion can survive the loss of its sacred landscapes).

Kwaio people do not worry about rising seas. They live in the mountains of Malaita, a large island in the Solomon’s. Kwaio villages sit in bush clearings, close to shrines adorned with ancient skulls. Despite the efforts of generations of missionaries, Kwaio still practices their ancestors’ religion.

Elsewhere in the Pacific, there are attempts to resurrect lost gods. On Tahiti, for example, Moana’ura Walker, a veteran anti-nuclear and pro-independence campaigner, has declared himself a pagan, and rebuilt an ancient temple in the forest outside Papeete, where large ceremonies are now held. For Walker and similar activists, North Sentinel is a symbol of a post-colonial future, not some sad remnant of the past.

This tribe lives 60,000 years in isolation.

North Sentinel Island is a small land area of about 45 square kilometers located on the Andaman Islands southwest of Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal. The island is under the control of India. They banned all trips to the island because travelling there is too dangerous. As a result, we know very little about this place and its inhabitants from Sentinel. What we know is that they are one of the oldest isolated cultures in the world - a pre- Neolithic group. They did not have any critical contacts for 60,000 years. Where they came from and when exactly did, they get there remains a complete mystery.

North Sentinel Island

Sentinel Island North is home to a pre-Neolithic tribe that is as vulnerable as it is mysterious.

According to researchers, the population of the island of North Sentinel ranges from fifty to several hundred people. However, there is no certainty, because no one can calmly set foot on the island. It is hard to imagine a place not affected by modern civilization. The tribe of the island of Sentinel protects itself with bows and arrows, and they can kill anyone who comes too close. This place is so dangerous that it is called the Forbidden Land.

Who are the Northern Sentinels?

Sentineling belong to the group of Andaman tribes. Only three of the five tribes that Europeans first registered in the Andaman Islands are still alive. The other two are already extinct. The three surviving tribes are Jarawa, Onge and Sentinel. Andaman’s are a very mysterious group of people because the results of genetic research are widely contradictory. Also, the researchers were unable to get close enough to the North Sentinel to collect DNA samples. Therefore, many assumptions about them were extrapolated from other Andaman populations.

Since DNA results differ and there are conflicting theories about their migration, the exact origin and kinship of the Andaman are unknown.

What do genetic studies tell us?

Different evolutionary lines Genetic studies conducted in the early 2000s by Lalji Singh, director of the Indian Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology, showed that Jarawa and Onga have genetic differences from each other that indicate either different migrations from Africa or their origin. He suggested that during the Ice Age, a land bridge connected Myanmar to the Andaman Islands. Migrations occurred on the islands at some point when the water level was lower, but when the water rose again, the islanders were isolated.

Without the DNA of the Northern Sentinels, Dr Singh could not definitively determine whether they arrived at the same time as the rest of the Andaman, or if they were even the same group, but he said:

The Sentinels are the only pre-Neolithic tribe left in the world where there were no contacts.

Possible unknown hominin

Mondal et al. recently conducted an interesting study, the results of which were published on June 25, 2016, in the journal Nature Genetics. Their results show that the Andaman’s (including the Sentinels) have an archaic human ancestor who has since become extinct. Also, the populations of Asia and the Pacific (including the Andaman) have migrated in a single wave and expansion, in contrast to the earlier theory of multiple streams from Africa.

Scientists are still arguing when the Andaman and Sentinel arrived, as well as where. Some DNA studies show that they could migrate from mainland India. Since they do not have the genetic mix that occurs when different groups of people come together, the group and their culture seem to have remained unchanged.

Little known culture

As one would expect from an isolated ancient culture, Sentinels lead a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. They are similar to other Andaman, eating lizards, berries, pigs and seafood, which they catch on the surrounding reefs. Defend themselves with weapons, such as bows, arrows, and handmade spears. They also engage in fishing and use rafts and canoes as a melt of funds.

Their need for protection

The Government of India declared the island of North Sentinel, including five kilometers extending outward, an exclusion zone. People are forbidden to go there. The ban on fishing is a source of food for the islanders. Removing contact with strangers also prevents the spread of fatal diseases in a population that does not have immunity. Also, the law prohibits visiting this island, as the islanders may well kill these guests. Finally, the surrounding waters present another risk: the seas tend to be very stormy, and the coral reefs surrounding the island caused some boats to run aground during a storm.

There were frequent cases when the islanders killed the unfortunate sailors, although there were cases of salvation. In any case, the government is making every effort to

Early interactions

Although there is no evidence that the Sentinels were or ever were cannibals, they certainly left an impression on anyone who saw them. Perhaps it was their terrible displays that made Marco Polo, a famous explorer who travelled around Asia, say about the Andaman:

"But they are the cruelest generation, and they eat everyone they can catch if you are not their race."

The earliest mention of any interaction with the islander’s dates back to 1771 WHEn the British surveyor John Ritchie saw "a lot of lights" when he sailed past the island during a research trip. In 1867, an Indian merchant ship called Nineva wrecked on a nearby reef. A tribe attacked them, but the team was able to repel the attacks until the Royal Navy finally rescued them.

The capture of the Northern Sentinels

In the late 1800s, British explorer Maurice Vidal Portman made several expeditions to the North Sentinel Island. He sought to learn more about the island for the British Empire. As soon as they landed safely on the island, they decided to explore it. The team discovered several paths and abandoned villages. They eventually found and captured six islanders and drove them back to Port Blair, South Andaman Island, to learn more about them. After some time, the prisoners fell ill, and two of them died.

This happened because they did not have immunity to deal with common infections of the modern world. The British took the remaining prisoners back to the island and released them to people with bundles of gifts.

Self-preservation

Many ships have capsized on reefs over the years. Some men survived, while others died. More recently, in 2006, a message appeared about two sailors who did not take into account the exclusion zone and decided to fish near the island. But when they woke up, they drifted too close to the island. Unfortunately, the islanders killed the fishermen and buried them in the sand.

There is documentation suggesting that people who roam the island are facing severe consequences.Northern Sentineling hold violent demonstrations, gesturing and throwing spears and arrows if a ship or helicopter approaches too close. However, if it were not for their self-protective behavior, perhaps they would also have died out, like the other tribes of the Andaman Islands.

This forbidden land is protected by the government, its people, and the environment. Over time, we will see if the Sentinels can reflect the problems that led to the disappearance of their Andaman neighbors. They must remain isolated or, most likely; they will die.

The natives killed a U.S. preacher who arrived on a forbidden island

The inhabitants of the island of North Sentinel are one of the last fragments of the world to live without any meaningful contact with the outside world. Indian authorities have banned strangers from going to the island to protect the natives and prevent possible incidents. John Allen Chau, a 27-year-old U.S. citizen who has been called a missionary by several Christian organizations, violated the ban and was reportedly killed by bow arrows.

It is alleged that Chau had been trying for a long time to hire fishers to take her boat to an isolated island, and despite warnings from people, she had managed to arrange transportation last Saturday. The fishermen took him by boat near the island, and he reached the island alone by kayak.

According to the fishermen, the first arrow had already hit the American on the beach, and then his body had already been taken to the interior of the island.

According to historians and anthropologists, the tribes living on the Andaman Islands have lived in the area for thousands of years. The most isolated city in the North Sentinel Island, which has been under direct contact with about 100 inhabitants for 25 years. It has been known that islanders have often been hostile to strangers who have accidentally or illegally arrived on the island - for example, two Indian fishermen came to the island in 2006. When a helicopter arrived to pick up their bodies, they also whistled at the aircraft.

According to Indian police, a murder investigation has been launched into "an unknown number of tribal members." Still, a more specific criminal investigation concerns the seven people who helped Chaul reach the island.

The Chau family announced on social media that they forgave the killers, and called on the Indian authorities to release the people who helped reach the island of Chaul. His family justified Chau's actions for religious reasons and a desire to proclaim Christianity.

Sophie Greg, a senior researcher at Survival International, commented that while visiting the forbidden island, Chau posed a threat to her safety which of the tribe.

"It is one of the most endangered tribes in the world. It could have transmitted infectious diseases that could wipe them off the face of the earth," Grig stressed.

Everything we all know About the Isolated Sentinelese People of North Sentinel Island

The death of an American tourist who illegally visited the isolated North Sentinel Island had drawn the world's attention to the tiny island's reclusive inhabitants. They're one among the few mostly "uncontacted" groups left within the world. They owe that isolation partly to geography -- North Sentinel may be a small island, off the most shipping routes, surrounded by a shallow reef with no natural harbors -- partly to protective laws enforced by the Indian government to the fierce defense of their home and their privacy. But they are not entirely uncontacted; over the last 200 years,

Outsiders have visited the island several times, and it often ended badly for each side.

Who Are the Sentinel’s?

According to a 2011 census effort, and based on anthropologists' estimates of how many people the island could support, there are probably somewhere between 80 and 150 people on North Sentinel Island. However, it might be as many as 500 or as few as 15.

The Sentinelese people are associated with other indigenous groups within the Andaman Islands, a sequence of islands in India's Bay of Bengal.

Still, they've been isolated for long enough that other Andaman groups, like the Onge and the Jarawa, can't understand their language.

Based on a single visit to a Sentinelese village in 1967, we know that they live in lean-to huts with slanted roofs; Pandit described a group of huts, built facing one another, with a carefully-tended fire outside each one.

We know that they make small, narrow outrigger canoes, which they maneuver with long poles in the relatively shallow, calm waters inside the reef. From those canoes, the Sentinelese fish and harvest crabs.

They're hunter-gatherers, and if their lifestyle is anything like that of related Andamanese peoples, they probably live on fruits and tubers that grow wild on the island, eggs from seagulls or turtles, and small game like wild pigs or birds. They carry bows and arrows, as well as spears and knives, and unwelcome visitors have learned to respect their skill with all of the above. Many of those tools and weapons are tipped with iron; the Sentinelese probably find washed ashore and work to suit their needs.

The Sentinelese weave mesh baskets, and they use wooden adzes tipped with iron. Salvage crews anchored near the island in the mid-1990s described bonfires on the beach at night and the sounds of people singing. But so far, none of the Sentinelese languages is known to outsiders; anthropologists usually make a point to refer to people by the name they use for themselves, but no one outside North Sentinel Island knows what the Sentinelese call themselves, let alone how to greet them or ask what their view of the world and their role in it looks like.

Why Don't the Sentinelese Like Visitors?

One night in 1771, an East India Company vessel sailed past Sentinel Island and saw lights gleaming on the shore. But the ship was on a hydrographic survey mission and had no reason to stop, so the Sentinelese remained undisturbed for nearly a century until an Indian merchant ship called the Nineveh ran aground on the reef. Eighty-six passengers and 20 crew managed to swim and splash their way to the beach. They huddled there for three days before the Sentinelese decided the intruders had overstayed their welcome -- a point they made with bows and iron-tipped arrows.

Western history only records the Nineveh's side of the encounter, but it's interesting to speculate on what might have been happening in Sentinelese villages behind the scenes. Was there a debate about how to handle these newcomers? Did the shipwreck victims cross a boundary or violate a law unknown to them, prompting the Sentinelese to respond, or did it just take them three days to decide what to do?

The Nineveh's passengers and crew responded with sticks and stones, and the two sides formed an uneasy detente until a Royal Navy vessel arrived to rescue the shipwreck survivors. While they were in the neighborhood, the British decided to declare Sentinel Island part of Britain's colonial holdings, which mattered only to the British until 1880. That's when a young Royal Navy officer named Maurice Vidal Portman took charge of the Andaman and Nicobar colony. Portman fancied himself an anthropologist, and in 1880 he landed on North Sentinel Island with a large party of naval officers, convicts from the penal colony on Great Andaman Island, and Andamanese trackers.

They found only hastily-abandoned villages; the people seem to have seen the intruders coming and fled to hiding places further inland. But one elderly couple and four children must have lagged, and Portman and his search party captured them and carried them off to Port Blair, the colonial capital on South Andaman Island. Soon, all six of the kidnapped Sentinelese became desperately sick, and the elderly couple died in Port Blair. Portman somehow decided it was a good idea to drop off the four sick children on the beach of North Sentinel along with a small pile of gifts. We have no way to know whether the children spread their illness to the rest of their people, or what its impact might have been.

Is It Possible to Make Friends?

A hundred years after the wreck of the Nineveh, a team of anthropologists led by Trinok Nath Pandit, working under the auspices of the Indian government, landed on North Sentinel Island. Like Portman, they found only hastily-abandoned huts. The people had fled so quickly that they left the fires still lit outside their homes. Pandit and his team left gifts: bolts of cloth, candy, and plastic buckets. But naval officers and Indian police accompanying Pandit also stole from Sentinelese, taking bows, arrows, baskets, other items from their unguarded homes despite the anthropologists' protests -- still not a great showing for the outside world.

Pandit and his colleagues kept trying to make contact, mostly by pulling a dinghy onto the beach, dropping off coconuts and other gifts, and beating a hasty retreat. The Sentinelese didn't care much for live pigs, which they speared and then buried in the sand, or plastic toys, which got much the same treatment. But they seemed pleased with metal pots and pans, and they quickly grew very fond of coconuts that didn't grow on the island. Pandit and his colleagues delivered them by the bagful, usually with bows and arrows trained on them until they departed. Twenty-five years passed that way, with no direct contact, but Pandit thought the visitors were building up some trust.

The visits were sporadic until 1981. A National Geographic film crew tagged along in 1974, and the director caught an arrow in the thigh for his trouble. The exiled King Leopold III of Belgium passed close to the island on a boat tour in 1975, and the Sentinelese warned him off with arrows. For some reason, the king was delighted by the whole thing.

In 1981, a cargo ship called the Primrose and her crew of 28 ran aground on the reef, in an eerie echo of the Nineveh. But this time, the sailors were rescued by helicopter, and later visitors to the island say that the Sentinelese seemed to have salvaged metal from the ship for their tools and weapons. For artisans used to working with scraps of metal that washed ashore, a whole boat must have been an incredible find. That same year, Pandit and his team stepped up their efforts, dropping by the island every month or two.

What Happens Now?

Given that history, it's not remotely surprising that the Sentinelese people saw American tourist John Allen Chau as a trespasser when he stepped onto their island earlier this month and stood on the beach singing hymns. They chased him away twice, but when he ventured a third time ashore, they're believed to have killed him. Now it appears they've buried his remains, as they did with the two Indian fishermen in 2006. The Indian government has now called off the search for Chau's body, citing danger to both search personnel and the Sentinelese people.

The incident has sparked discussion about protections for relatively uncontacted groups like the Sentinelese. Pandit has advocated leaving them be. According to the now-retired anthropologist, the Sentinelese have made it clear that they don't want contact and are doing just fine on their own. Indian officials continue to visit the island for periodic censuses (the last one was in 2011).

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.