Jack Kerouac Saved My Lives

On the 101st Birthday of an American Icon

"The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time. The ones that never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles.” --Jack Kerouac, On the Road (1957)

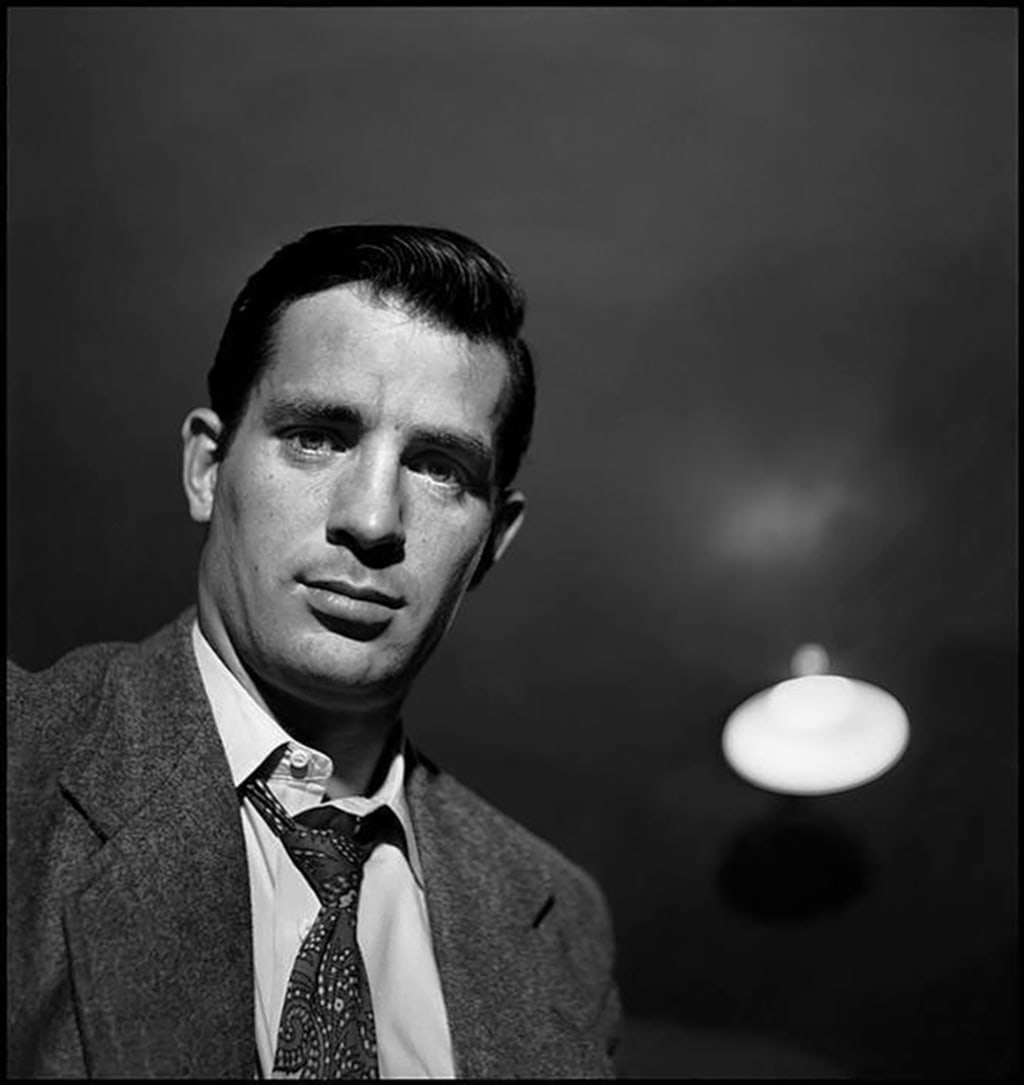

Jack Kerouac is a character who exemplifies a mythic America. His image stands out in my mind like Paul Bunyan or Pecos Bill, a character of legend. His face should be carved into a mountain.

I don't know Jack. At least, I don't know him as I should. I don't know him the way you should know a man that helped save your lives. Yes, I say lives, as in plural. I've had more than one and been through many incarnations. And Jack helped me get there. (As did Bill Burroughs, Alan Ginsberg, and the rest of the Beats. Ann Charters' book The Portable Beat Reader is a Biblical text to me. It nurtured my soul.)

Jack was an unreasonably handsome Devil of a man who went the length and breadth of the American Night, taking dictation on his travels, on Bop Kabbalah and Charlie Parker, on the bus terminals and backroads, the greasy, shitty diners and the small-town characters and big city hoods and the dirty, crawly, ratty aspects of life thrown against the backdrop of a mighty, massive Great Land. All the time searching, searching, searching...And for what, you may ask, was he searching? For what the true, deep, and forever reality of LIFE was? For what the world meant in those post-war years when Auschwitz, Hiroshima, lynchings, and both the promise and duplicity of American Life collided like the electrons of the Hadron Reactor with the goals and dreams of a New Era; creating a chain of dissension among the youth, or some of the youth, who saw through the well-clipped "Leave it to Beaver" facade of a world that the war years had taught them could be swept away at any time? After all, what had civilization, modern industrialized, Western civilization led to except the corpse pit at Belsen, the bombing of Dresden, and the Hydrogen bomb--newer and bigger and better and more industrialized ways to oppress and kill; the American Lynch Mob mentality and the "Strange Fruit" Billie Holiday had sung of swinging from sinister Southern trees?

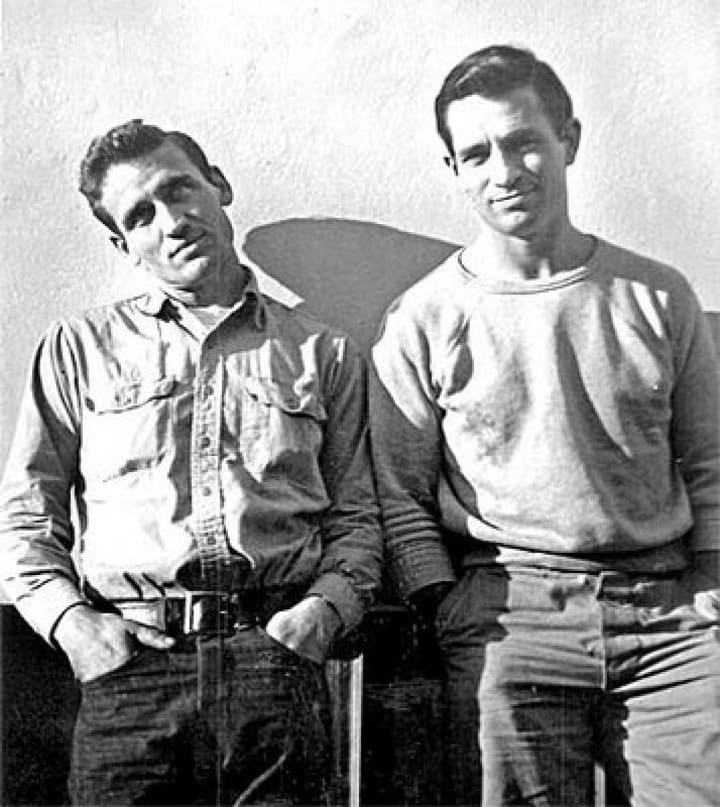

In all of this, Jack Kerouac wondered (as did so many others): What is real? What is eternal? "Life is Holy," he said, "and every moment precious." And to that end, he set about on endless rolls of type-script to document his restless, vagabond journey across America, the Real America, the ugly and forgotten and banal America of truck drivers, farm boys, indigents, immigrants, waitresses, benzedrine addicts, bad poets, and Dean Moriarty. Dean who was "Neal Cassady." Jack himself was "Sal Paradise." Two iconic literary inventions; real and not real; fantasy and reality merged.

On the Road is not easy to read. There is no place for the brain to "hone in" on the plot because there isn't one. That's not a criticism. Jack took a verbatim transcript of the moment-by-moment details of his life, of "Carlo Marx" and "Old Bull Lee", of the travels across the country while hitching his thumb out, of the profanities and peculiar characterizations of people whose lives, otherwise, are opaque ciphers to the rest of conventional society. He refused, like a mad and voracious monk, hungry for enlightenment, to be chained to the bourgeois world that promised nothing but more illusion. Beneath the facade, he knew, was the deep wellspring of Authentic Life; i.e. that which the System, which the Establishment, meant to curtail, rope in, and swallow in a deluge of false consumerism and phony sentiment.

Because for him were only the "mad men", hungry for everything. For him was only the Dean Moriartys who "spent a third of their time at the library, a third in jail, and a third in the loft reading books." Not an exact quote, but Cassady was searching for the real himself as well, looking to find the map in that literary jungle that beckoned, a "jail kid excited by the prospect of being a real intellectual." Not exact quotes, but you understand.

And in the ceaseless roil of poetry, in the minute-by-minute sacralization of ALL THAT WAS, Jack recorded the bits and pieces of this dream-like life, on huge, aforementioned paper rolls of typescript, in a way that no one ever had before. You could call it a literary belch, obsessive-compulsive madness, or a man escaping, outside the confines of what is dictated as acceptable intellectual rumination or even storytelling, to document the holy datum and errata of our ever-slipping lives, our crumbling time frame that slips from between our fingers, moment by precious moment, blowing away like cheap cigar smoke in a gentle wind.

Jack is the observer, the mendicant who has detached from the flow of life as much as he has embraced it, noting this experience, that experience, relating the poetry of the commonplace and mundane, each road leading him to everywhere, and nowhere. The ghost of Brother Gerard, who preceded him in death, walked with him. Someone said of Jack the Buddhist: "He'll die clutching a crucifix in his teeth." Which was probably true. You never depart the God, truly, who oversees your entry into this world. He'll be the same God, you can rest assured, that will see you out.

"Anyway, I wrote the book because we're all gonna die." So saith Jack, who understood. He clutched at the smoke of life as it disappeared through his fingers, always wanting more, because: minute-by-minute, it vanishes, and like Jack the Firewatcher atop Mount Desolation, you are left alone, with only your consciousness, and, in the end, it all disappears he knew; and God is Pooh Bear.

Jack wrote about the brutal fist of authority. On the Road, documents submerged American brutality lurking "like a faded flannel shirt" (as Burroughs wrote) beneath the outer shell of American exceptionalism. Jack accepted all and internalized all, but remained simply the chronicler of the pathology, never judging but only accessing the topography of the landscape; yet, still on a search for the true and eternal, that which was the truly sweet, compassionate heart of the human experience.

So, how did Jack Kerouac save my lives? By discovering him much later than Burroughs (whose inscrutable, sardonic cynicism is a panacea against the intellectual ills of a burdened existence, perhaps, disappearing into the void of his cut-up confusions of the standard communication between Reader and what is Read; observer and observed, so to speak), I was at a disadvantage, never accessing a complete picture of the Beat Scene. But, at a time in my life when life had lost ALL meaning, because I had, personally, been stripped of meaning and dignity, during the depths of my depressive state, I realized that life, as it was lived didn't have to rise to bourgeois conventions. That it was Dead on Arrival; hence, one could live "outside the law" in a sense, on one's terms, and simply observe a world that would seem more and more illusory, more and more insane. Jack Kerouac was no political radical; he detested the Hippie scene he helped birth, with its anti-American, anti-patriotic spirit of rebellion against a country he fought to understand, to be assimilated into; the perennial outsider who wished, desperately, to find his place, but knowing instinctively it was not his karma to do so.

He chronicled the quotidian lives of common people, and even dregs, and gave birth to a movement whose impetus was the ability to verbalize and discuss the barest, basic, most sensitive, and real aspects of existence, in a search for meaning and ultimate TRUTH. Whether he ever found the truth he was looking for, is doubtful. He died at the age of forty-seven of a brain hemorrhage, brought on by years of alcoholism. By then, former friends had abandoned him as a political "reactionary" or regressive, not understanding that he never wanted to lead a movement for the disenfranchised, or the rebellious, but that he wanted to preserve a substratum of existence, of experience that would be overlooked, disregarded, and forgotten; the lives of those who were likewise seeking: salvation, escape, and meaning.

One man recalls Kerouac telling him that he refused to edit his huge paper roll of a manuscript because "This manuscript has been dictated by the Holy Spirit."

No cuts. No interruption to the flow of the rhythm of the BEAT. The eternal Pulse of Life of which, like every good Buddhist, he knew he would return, again and again, until achieving that state in which there was NOTHING: no attachment, no suffering, not even the idea of peace. Just...

Happy birthday Jack. You saved my lives. You showed me that we all have our breakdowns, our burdens, our thistles and thorns and brambles, and pratfalls, along the way, while we're walking on the road. The one that never, ever ends...

...Not even yours.

Happy 101.

Jack Kerouac on the Steve Allen Show (1959)

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insight

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Comments (1)

It is a while since I read "On The Road" but Kerouac is a true American artistic great , excellnt story