Himalayan Shepherds of Uttarakhand: Culture, Migration, and Meadows

Himalayan Shepherds of Uttarakhand are traditional pastoral communities including Bhotias, Gaddis, and Garhwali villagers who practice seasonal transhumance, moving livestock between high summer meadows and lower winter valleys. Their long-standing grazing system supports local livelihoods, improves soil health, and reduces wildfire risks.

Shepherds in Uttarakhand — especially communities like the Bhotias, Gaddis, and local Garhwali villagers — continue a centuries-old pastoral tradition that has shaped both culture and ecology in the Himalayas. Their livelihood revolves around transhumance, a seasonal migration system where flocks of sheep and goats move between high alpine meadows (bugyals) in summer and lower valleys during winter. This cycle not only sustains local economies but also influences the Himalayan landscape through controlled grazing patterns that reduce fire risk and enhance soil fertility.

Seasonal Migration Patterns

Transhumance typically begins in May or June, depending on when the snow melts. As the high-altitude meadows open, shepherds lead their flocks to bugyals such as Dayara, Panwali, Kuari, Bedni, Ali, and the Nanda Devi outer ranges. Many herds climb to 3,500–4,500 meters where rich monsoon-fed grasses support rapid livestock growth.

Shepherds remain in alpine zones until September, when temperatures begin to drop. The return journey passes through mid-altitude villages for brief rests before descending to the Shivalik foothills, Doon valley, Yamuna valley, or Bhagirathi basin for winter grazing.

In regions around Mussoorie, flocks crossing roads in October–November are a common sight.

Bhotia pastoralists traditionally followed longer routes that connected India to Tibet, staying in high-altitude summer homes and wintering in valleys. These practices were significantly disrupted after the 1962 Sino-Indian border closure, which ended formal transborder trade.

Communities and Traditions

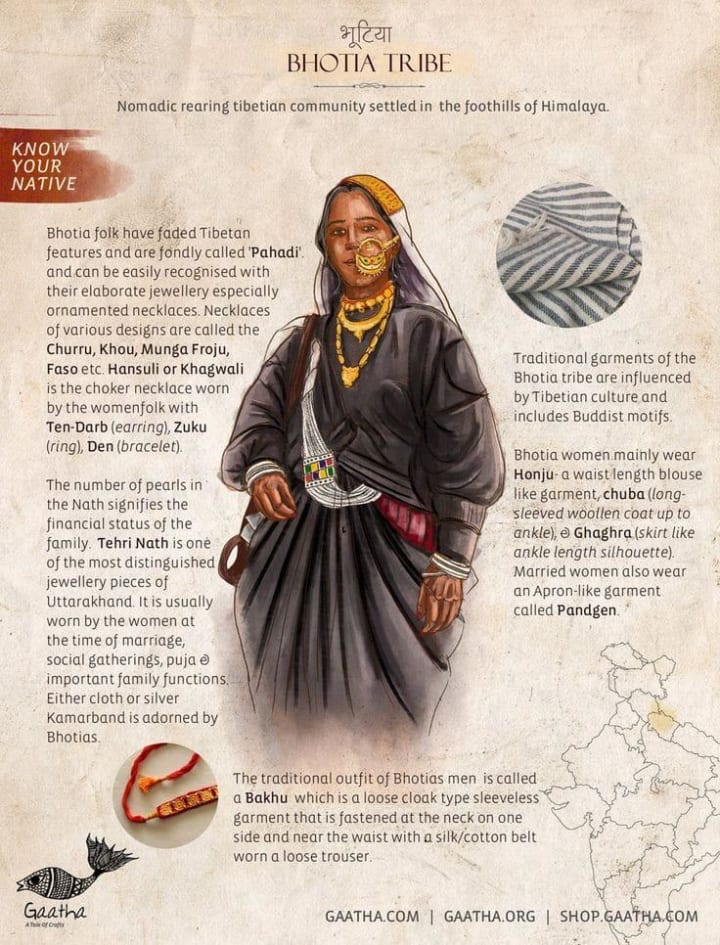

Bhotias

The Bhotia communities — including Johari, Tolchha, and Marcha Bhotias — have Tibetan links and historically balanced pastoralism with agriculture and cross-border trade in salt, borax, wool, and grains. Their dual-residence lifestyle, with summer homes in high valleys like Milam or Mana and winter settlements in lower areas, is a unique cultural identity of Uttarakhand.

Villages in the Har Ki Dun valley (Osla, Gangaad), Rupin–Supin region, Raithal, and Uttarkashi district maintain mixed livelihoods of farming and herding. During summers, entire families move to stone huts (chhanis) in bugyals — structures that trekkers often use as temporary shelters on trekking routes like Dayara Bugyal, Kedarkantha, Har Ki Dun, and Bedni Bugyal.

Wool and Handicrafts

Women in pastoral communities traditionally spin and weave:

- Pashmina shawls

- Pattu blankets

- Kullu/Garhwal-style wool clothing

- Carpets and socks (jhola bori)

However, machine-made synthetic wool and cheap imports have reduced income from these crafts, threatening a skill passed down through generations.

Challenges Facing Shepherds

1. Shrinking Grazing Rights

Due to conservation policies, major grazing areas — including parts of Nanda Devi Biosphere, Govind Pashu Vihar, Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, and Binsar — now have strict restrictions. Many shepherds pay increasing forest department fees, making the livelihood financially difficult. For example:

In the Bagori village cluster near Harsil Valley, where around 500 families once practiced seasonal herding, only 50–60 families continue today.

2. Youth Migration

Better education access and urban job opportunities pull younger generations away from pastoral work. The long months of isolation in high meadows and unpredictable market prices for wool discourage continuity of the tradition.

3. Climate Change

Erratic snowfall, early monsoons, and shorter grass-growing seasons affect both migration timing and livestock health. Unpredictable weather also increases risks of predator attacks, especially from snow leopards, wolves, and Himalayan black bears.

4. Weak Wool Economy

Indian wool prices remain low compared to synthetic fibers. Transporting raw wool from remote villages to markets like Dehradun, Rishikesh, and Delhi reduces profits further.

Community Responses

Organizations such as Mountain Shepherds, Himalayan Ark, and local eco-tourism cooperatives are helping by:

- Training shepherds and youth as trek guides and naturalists

- Creating community-owned homestays in regions like Nanda Devi Outer Sanctuary

- Promoting fair-trade wool products

- Reviving traditional knowledge for sustainable land management

Cultural and Ecological Role

Shepherds play a crucial role in Himalayan ecology:

1. Natural Fire Control

Summer grazing removes dry biomass that would otherwise fuel forest fires — a growing issue in Uttarakhand.

2. Soil Fertility and Meadow Health

The constant movement of herds naturally aerates soil, while dung enriches the nutrient cycle of fragile alpine meadows.

3. Maintaining Biodiversity

Bugyals remain open because of grazing. Without it, many meadows quickly convert to shrubland, affecting endemic flora like:

- Brahm Kamal

- Blue Poppy

- Fritillaria cirrhosa

4. Cultural Bridges

Shepherd huts often serve as informal shelters for trekkers, creating memorable cultural exchanges. Meeting shepherds on treks like Dayara Bugyal, Kedarkantha, Bali Pass, Kuari Pass, and Rupin Pass gives hikers a glimpse of an ancient Himalayan lifestyle that predates roads and tourism.

Conclusion: The Future of Uttarakhand’s Shepherds

Shepherds remain one of the strongest living symbols of Uttarakhand’s mountain heritage. Their traditional migration patterns reflect a deep understanding of the Himalayas, shaped by centuries of adaptation. While challenges such as shrinking grazing rights, climate pressure, and economic limitations threaten this lifestyle, ongoing efforts in eco-tourism, community-led conservation, and handicraft revival offer hope.

Recognizing the cultural and ecological value of shepherds is essential not only to preserve Himalayan traditions but also to maintain the fragile balance that sustains the region’s alpine ecosystems.

About the Creator

Mountains Curve

I’m a passionate traveler with an insatiable curiosity for exploring new corners of the world. Beyond my love for adventure, I find joy in DIY crafts, cooking, planting, spending time in forests, and diving into anything new to learn.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.