French Fury: The Jet Powered Mach 0.6 Interceptor That Could Reshape Air Defence

Fast and furious autonomous interception of drone targets

It seems that I’m writing stories about new drones and drone defences every week. Last week it was the Estonian Micromissile Mark 1. This week’s offering is a French drone capable of Mach 0.6 (700 kph/440 mph) with very high manoeuvrability.

What is the Fury?

It’s a high-speed, unmanned aerial system designed specifically for the interception and neutralisation of airborne threats. It is the product of ALM Meca, a small-to-medium enterprise based in Alsace, France.

Unlike many contemporary drone projects that originate from major primary contractors such as Dassault or Thales, the Fury is a notable example of independent innovation. The aircraft occupies a specific niche in the air defence market, acting as a dedicated interceptor for fast and evasive targets.

Its primary role is to counter the increasing prevalence of ‘kamikaze’ drones, similar to the Shahed-type models frequently observed in Ukraine and occasionally the Middle East.

As I have frequently written about, in these environments, traditional surface-to-air missiles are often considered too expensive for the engagement of low-cost loitering munitions. The Fury offers a middle ground, providing the performance of a guided missile with the reusable nature of a drone platform. Note ‘re-usable’ — it’s tied in to deployment strategy, which I’ll cover later in this piece.

Capabilities

The operational performance of the Fury is defined by its speed and structural resilience. The interceptor is capable of reaching a maximum speed of 700 kph (~420 mph). This speed is approximately three times faster than many of the target drones it is designed to hunt, such as the propeller-driven models used for long-range strikes.

Such a speed advantage allows the Fury to close the distance to an incoming threat rapidly, reducing the window of opportunity for the target to complete its mission.

In addition to linear speed, the Fury is engineered for extreme maneuverability.

The airframe is capable of withstanding forces of up to 20G during aggressive flight maneuvers. This exceeds the structural limits of many piloted fighter aircraft and conventional drones. This high G-load tolerance ensures that the interceptor can follow the evasive flight paths of unpredictable targets without suffering structural failure.

While specific details of its armament remain confidential, its design suggests a focus on kinetic impact or collision to neutralise targets, ensuring a high probability of kill through direct physical engagement.

Unique propulsion — almost

The defining technical characteristic of the Fury is its turbojet propulsion system.

The ALM Meca turbojet operates at 120,000 RPM, supported by specialised ceramic bearings. The system is managed by an integrated Electronic Control Unit (ECU) that ensures stable thrust delivery during high speed 20G manoeuvres.

With a maximum thrust capability estimated between 250 N and 300 N for custom variants, the engine provides the ‘detonating performance’ required for rapid interception.

The modular ‘Plug & Play’ design allows the entire jet unit to be swapped or serviced with minimal ground equipment, ensuring high operational availability. By internalising this technology, ALM Meca has avoided the supply chain vulnerabilities that affect competitors relying on third-party propulsion.

The turbojet runs on kerosene and provides the high thrust-to-weight ratio necessary for the drone’s 700 km/h top speed.

The version utilised in the Fury is an optimised variant designed for the rigours of high-performance combat. This ‘quasi-unique’ engine allows the French system to operate in a category of its own, offering jet-engine performance in a form factor that remains manageable for rapid deployment.

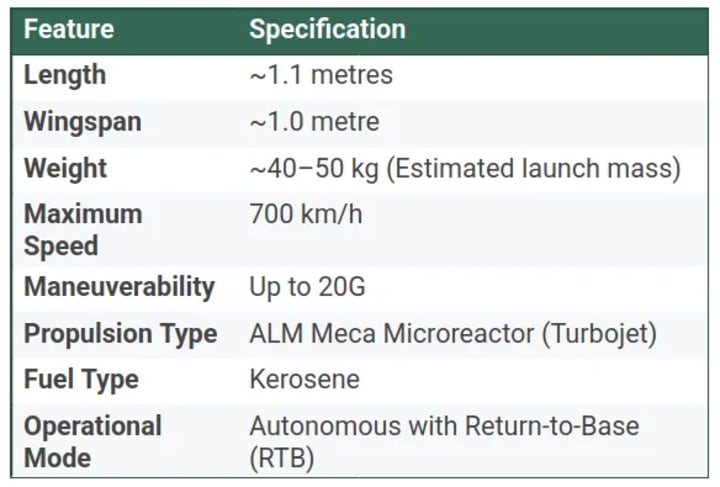

Specifications

The technical specifications of the Fury reflect its purpose as a lean, high-acceleration interceptor.

The aircraft resembles a small combat jet, featuring a streamlined fuselage and swept-back wings to reduce drag at high subsonic speeds. Its compact size ensures that it can be launched from portable platforms, providing a flexible response for ground forces.

Comparable interceptors

The Fury enters a competitive field where other nations are seeking low-cost ways to defeat drone swarms. The most direct comparison is the Roadrunner, developed by the American company Anduril. The Roadrunner is also a turbojet-powered interceptor capable of high speeds and kinetic engagement.

However, the Fury is distinct for its purely French origin and the fact that it was developed with minimal initial support from the French Ministry of the Armed Forces.

Other systems, such as the Ukrainian-developed ‘Sting’ or various FPV interceptors, typically rely on electric motors and propellers. These are significantly slower than the Fury, often reaching speeds of only 150 to 200 kph. While effective against basic surveillance drones, they struggle to intercept the latest generation of jet-powered loitering munitions.

The Fury occupies a higher tier of performance, closer to the Black Bird interceptor from Alta Ares, which is also providing jet-speed solutions for the European theatre.

Return to base (RTB) capability

The inclusion of an RTB capability is a critical feature that distinguishes the Fury from a traditional interceptor. This function is essential for economic sustainability and tactical flexibility.

In ‘no-fire’ situations — where a target is neutralised by other means or identified as non-hostile — the Fury can return to its launch point. This prevents the loss of an expensive airframe and its sophisticated turbojet.

The recovery process typically involves a parachute deployment system. Automated algorithms monitor airspeed and wind direction to execute a ‘pitch-up’ manoeuvre, reducing velocity before the canopy is released ballistically or passively. This ensures a soft touchdown, allowing the most costly components, such as the turbine and avionics, to be salvaged and refurbished for subsequent missions, and usually the airframe as well.

Control and guidance

The Fury drone interceptor developed by ALM Meca serves primarily as the high-performance platform (airframe, mechanical integration, and turbojet propulsion system), but its control and guidance capabilities are enhanced through collaboration with French defense tech company Alta Ares, which provides the mission system components.

This partnership integrates advanced AI and autonomy features, making the system suitable for its ultra-high-speed (700 km/h) and high-G (up to 20G) operations, where real-time human remote piloting would be challenging due to latency, reaction times, and the physical demands of such manoeuvres.

Key details on control:

- Autonomous Guidance and AI Integration: Alta Ares equips variants like the Black Bird (derived from Fury) with their Pixel-Loc AI software, enabling automatic detection, identification, tracking, and interception of targets such as Shahed-type kamikaze drones.

The system uses multi-sensor fusion (e.g., combining optical, infrared, and other sensors) for real-time threat processing and precise, GNSS-free (GPS-independent) terminal guidance.

This allows the drone to autonomously pursue and neutralise threats without constant human input, achieving reported interception rates of around 70% in testing against Shahed equivalents.

- Operational Mode: While specific Fury-only details are limited (as ALM Meca focuses on the hardware platform), the integrated system operates with high autonomy, particularly in the terminal phase of interception.

Human operators probably provide high-level mission commands (e.g., designating patrol areas or initial targets), but the drone handles flight adjustments, evasion, and engagement independently via AI algorithms.

This “human-on-the-loop” approach (oversight without direct control) is common for such fast interceptors to mitigate risks like signal jamming or delays in remote piloting.

Direct remote human control at these speeds would not be feasible, as even minor latencies could lead to mission failure.

- Testing and Validation: The Alta Ares-enhanced system (including Fury-derived platforms) has been demonstrated in NATO trials, where it successfully intercepted target drones using its autonomous capabilities.

It’s designed for real-world scenarios, drawing from Ukrainian front-line feedback, emphasising robustness against electronic warfare and GNSS denial.

Public information on the exact autonomy level (e.g., full vs. semi-autonomous) or specific sensors is sparse, as both companies keep operational details proprietary for security reasons. However, the emphasis on AI-driven, real-time decision-making confirms it’s far beyond traditional remote-controlled drones, aligning with modern trends in counter-drone warfare.

Conclusions

The Fury represents a significant shift in French defence innovation. It demonstrates that a small enterprise can produce a world-class interceptor system without the massive overhead of a major industrial group. This is reminiscent of Ukraine’s ability to innovate, prototype and deliver.

By internalising the production of the jet, ALM Meca has ensured a level of technical sovereignty that is often lost in international supply chains. However they did need to buy in the control, guidance and targeting system, but from another French company, not the US.

The success of the Fury will likely depend on whether the French state or international partners move from observation to procurement. In an era where the cost of air defence is a critical concern, a French-made, ultra-fast drone that can neutralise expensive threats at a fraction of the cost of a missile is a compelling proposition.

Nevertheless it is good to see reduced dependence on increasingly questionable US technology partnerships.

Originally published on Medium

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.