At fifty, I found myself drawn irresistibly toward the study of complexity, though the first stirrings of this realization began in my thirties. As a postdoc, I was introduced to physiology, and in particular, the physiology of chronic diseases. I noticed something that unsettled me. We were experimenting on a swine model of renal artery stenosis. Two animals, genetically similar and placed on an identical protocol, could be induced by the same pathological condition at the same moment, yet the disease development unfolded in dramatically different ways. These differences were not due to inconsistencies in protocol implementation or random error in assessment. They arose from subtle differences in initial conditions, invisible influences, and hidden physiological interactions along the way. The neat, parallel lines promised by conventional statistics simply did not exist in reality.

When I shared these observations, the responses were cautious. Many colleagues trusted the reductionist frameworks they had been trained in. Those models had carried science forward and led to genuine discoveries. Abandoning them for something as elusive and difficult to pin down as complexity was not an easy step. Their hesitation was not hostility. It was confidence in a system that had delivered results. Yet for me, the pull toward complexity came from what I could see with my own eyes. Cancer, chronic diseases, immune disorders, all bore the unmistakable marks of complex systems. Their nonlinear dynamics and unpredictable trajectories demanded a different approach, different markers.

My conviction deepened when I encountered systems biology. At a slightly different landscape, it echoed the same insight I had begun to see at the clinical level. Some diseases are not linear. They are complex systems. I began to wonder if systems biology exists, why not systems physiology, or even systems medicine? That thought stayed with me. Unfortunately I should admit that even a decade later, I see the resistance to leaving behind simplistic models and adopting complex approaches when necessary. Even today, I still come across papers by researchers in medicine and biology working in complex systems who voice the same frustration. The dominant mentality remains reductionist, even though such approaches often fail to capture the reality of the phenomena they study.

With my background in biomedical engineering and MRI, imaging became my first lens into this world. I tried to map dynamic relationships between phenotypes, hoping medical images could reveal the hidden interplay of disease. I pushed the boundaries of the tools I knew, new contrast agents, advanced signal processing, experimental MRI sequences. But it soon became clear that not all the key players would appear in the images. This was a major issue in a complex system that overlooking even one element could distort the trajectory beyond recognition.

Later, when I began working in radiation oncology, the point crystallized. Cancer seemed the ultimate stage for complexity in medicine. Images I had access to showed one layer of the story, but the deeper drama unfolded at the cellular scale. I soon realized that the clinical data required to capture that level would either never be fully attainable or would come at an extraordinary cost. So I turned to what I half-jokingly called the “poor man’s approach”; agent-based, evolutionary game theory simulations. In these models, virtual players could battle, cooperate, and evolve, creating a living representation of cancer’s dynamics. By linking these simulations back to imaging, I began to see a way to calibrate models, extract information I could not measure directly, and test hypotheses that traditional methods could never reach.

As I pieced these strands together, I began to see that this struggle was not unique to medicine. Wherever complexity appeared, e.g. economics, stock markets, public policy, the same reductionist instinct prevailed, and the same impasse followed. People clung to the tools they trusted, even as those tools failed to explain the turbulence in front of them. Medicine was simply another arena in this larger struggle between simplicity and reality.

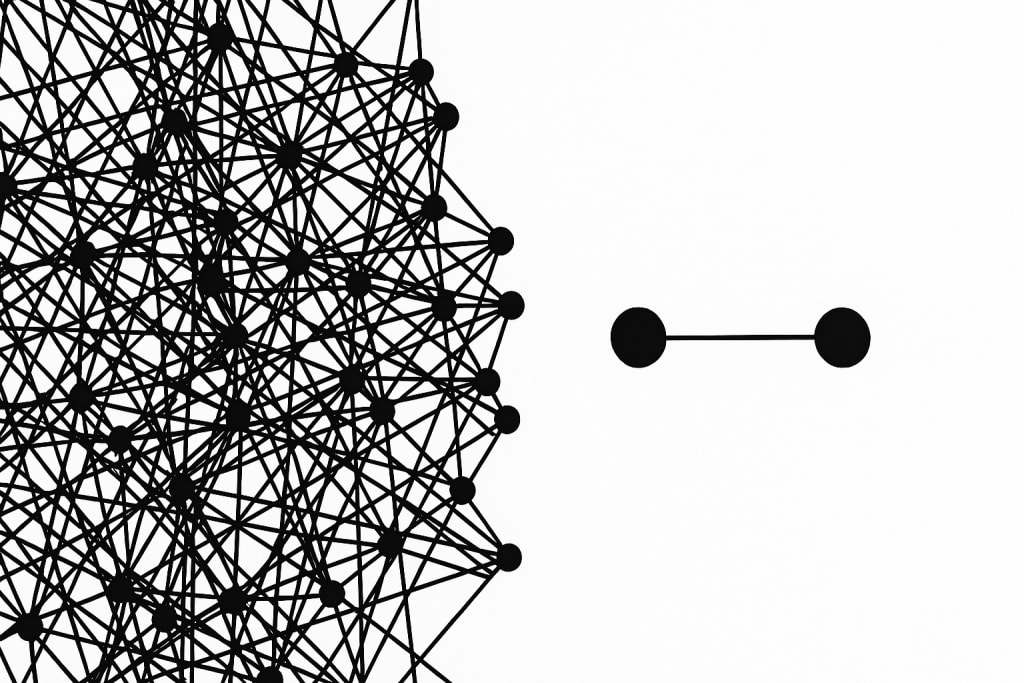

The truth is that reductionism has served us extraordinarily well. Many of the world’s great discoveries emerged from it. But reducible problems, the ones best suited to reductionist methods, are largely behind us. What remain are the unsolved challenges such as cancer, chronic illness, immune disorders, societal systems. They are complex, woven into nonlinear dynamics, feedbacks, and hidden interdependencies. At times they may appear linear, offering the illusion that old analytical methods still work. But when we reflect on how long we have wrestled with these questions, with only incremental progress, and results that are often not reproducible, the truth becomes clear. applying linear, statistical tools to these problems has, if not failed outright, fallen far short of success. To move forward, we must embrace the complexity at their core.

Today, my journey feels less like a detour and more like convergence. My engineering roots had given me mathematics and imaging. My immersion in physiology and biology has shown me the messy, nonlinear side of life. Cancer had revealed itself as the ultimate proving ground. Together, these experiences fused into a new beginning. Complexity was no longer an abstract fascination. It was the key to understanding life’s most difficult questions and once I saw it, there was no going back.

About the Creator

Banzan A. B.

Venturing through ideas, navigating towards balance, I'm an academic steering voyages toward subtle consensus and implicit harmony.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.