Drone Defence: Estonian Micro Missile Mark 1

Small, effective, here's an analysis of these AI guided interceptors to be adopted by the UK's Royal Navy

Miniaturisation and AI have been the watchwords of recent developments principally in the domain of drones. And drone defence. Now this week has brought news of an Estonian anti-drone micro-missile.

Design of such a missile presents guidance challenges which I will analyse later in this story, but first, the details of the missile.

The missile news

In January 2026, British engineering firm Babcock signed a memorandum of understanding with Estonian start-up Frankenburg Technologies to develop a naval launch system for the Mark 1 micro-missile. This collaboration aims to provide a cost-effective, containerised solution to defend maritime and critical infrastructure against massed drone attacks.

This interceptor is designed to address the asymmetric threat posed by mass-produced UAVs and loitering munitions. By prioritising low cost mass production, the project should provide a sustainable solution to the challenges of modern aerial warfare.

Strategic context

The concept for the Mark 1 originated from a collaboration led by the Estonian firm Frankenburg Technologies. The development process was exceptionally rapid, moving from initial design to live-fire testing within thirteen months. The UK has played a pivotal role in the further development and integration of the system.

The primary objective of the Mark 1 is to provide ‘affordable mass’. As I have written about extensively, traditional air defence systems often rely on interceptors that cost hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of dollars. When faced with swarms of cheap drones, using such sophisticated weaponry is economically unsustainable.

The Mark 1 aims to rectify this imbalance by providing a guided missile that is relatively cheap to manufacture while remaining effective against its intended targets.

Technical characteristics and design

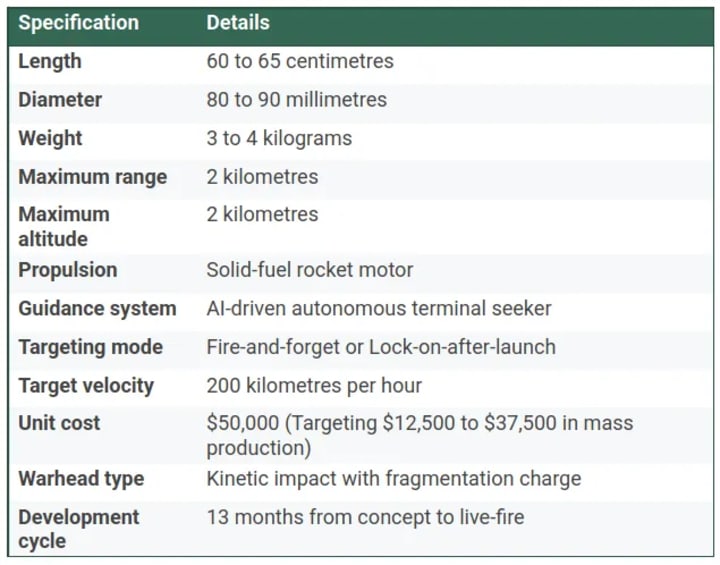

The Mark 1 is notable for its compact dimensions, measuring approximately 60 to 65 centimetres in length. This makes it the smallest guided missile currently under development in Europe. Its small size allows for high portability and the potential for multi-missile launch platforms.

Despite its modest proportions, the missile is engineered to intercept targets at altitudes of up to 2 kilometres (~7,000 feet).

A defining feature of the missile is its guidance system. It employs artificial intelligence for autonomous terminal guidance.

Current performance data indicates that the missile has achieved a hit rate of approximately 56 per cent in trials. While this is lower than the performance of high-end traditional systems, the developers are engaged in an iterative process to improve this figure.

The target for future versions of the software and hardware is a 90 per cent success rate. In a saturation attack, the ability to launch numerous inexpensive missiles offsets a lower initial accuracy rate compared to single-shot expensive alternatives.

Warhead

The missile utilises a kinetic-based approach to neutralise its targets. Given its small dimensions, the missile does not carry a large conventional high-explosive payload. Instead, it relies on a combination of high-velocity impact and a miniaturised explosive fragmentation sleeve to destroy UAVs.

Guidance

The missile is designed to operate as part of an integrated air defence network, rather than as a fully autonomous standalone sensor platform. Because its internal seeker has a limited field of view (assumed no articulation) due to its small size, the initial acquisition process relies on external data.

There are two guidance modes. For targets which are visible, the seeker can be locked on while the missile is still on the launch tube.

The other mode is hybrid.

Integration with external radar

The missile is typically cued by a primary ground-based or naval radar system. This external sensor identifies the incoming threat and calculates its vector, altitude, and speed. Before the missile is launched, this targeting data is uploaded to the onboard flight computer. This ‘pre-launch handover’ ensures the missile is pointed towards the correct sector of the sky where the threat is located.

Initial flight phase

Upon launch, the missile follows a programmed trajectory based on the coordinates provided by the primary radar. During this ‘mid-course’ phase, the missile does not necessarily see the target itself. Instead, it uses its internal inertial measurement unit to navigate to the predicted ‘basket’ — a specific volume of airspace where the target is expected to be.

Transition to autonomous seeker

Once the missile reaches the designated engagement zone, it activates its internal seeker. At this stage, the onboard artificial intelligence takes control. The AI scans the immediate environment using its miniaturised sensors to find a target that matches the electronic or visual signature of UAV.

Terminal lock-on

When the AI identifies the target within its field of view, it transitions from a general flight path to terminal guidance. The system ‘locks on’ and autonomously calculates the final intercept course. Because this process happens locally on the missile, it can continue to track the target even if the primary radar loses the signal or if the area is subject to heavy electronic jamming.

Design challenges

Computational and power constraints

The most immediate challenge is the ‘power/performance’ trade-off. Standard AI models for object recognition require substantial processing power, typically provided by large GPUs. In a micro-missile, engineers must utilise ultra-low-power embedded processors, such as specialized Neural Processing Units or Field Programmable Gate Arrays.

These components must perform complex image processing and trajectory calculations in real-time while drawing minimal current from a small battery. To achieve this, software developers use ‘quantisation’ — a process of reducing the precision of mathematical weights within the AI model.

Thermal management

Heat dissipation is a critical failure point for miniaturised electronics. AI processors generate intense localised heat during the high-intensity ‘terminal phase’ of a flight. In a larger missile, there is sufficient surface area or specialised cooling systems to manage this.

Sensor fusion and noise reduction

Miniaturised sensors — such as infrared cameras or micro-Doppler radars — are inherently noisier and less sensitive than their full-sized counterparts. The AI must be capable of ‘sensor fusion’, which involves combining data from multiple low-quality inputs to create a single, high-fidelity picture of the target.

Because the Mark 1 is designed to operate without a data link to avoid jamming, the onboard AI is solely responsible for filtering data clutter in ‘visually’ chaotic environments (waves at sea, hills, buildings, trees. power lines on land). This requires the use of ‘pruned’ neural networks — models that have been stripped of unnecessary data to focus exclusively on the specific signatures of UAVs.

Aerodynamic stability and control

The small scale of the Mark 1 introduces non-linear aerodynamic behaviours that are less prevalent in larger projectiles. At high speeds, small surface imperfections or atmospheric changes can cause significant instability. It’s a bit like the ‘butterfly effect’.

The guidance AI must not only track the target but also constantly adjust the missile’s flight surfaces to compensate for these micro-instabilities.

This requires the feedback control loop — the time between sensing a change and moving a fin — to be exceptionally fast. Any latency in the AI’s decision-making can lead to ‘over-correction’, causing the missile to oscillate and miss its target.

This feedback loop problem famously led to the naming of the ‘Sidewinder’ missile, way back in the early 1950s I recall, after the US snake.

Consequently, the integration of flight control and target guidance into a single, cohesive AI architecture is essential for the success of the MicroMark1.

Industrial collaboration and production

The industrial framework supporting the Mark 1 is international in scope. While Frankenburg Technologies holds the core intellectual property, manufacturing and development hubs have been established across several NATO member states. Poland has been identified as a primary location for large-scale production, with a goal of manufacturing up to 10,000 units annually.

In the UK, Babcock has signed up to develop a naval launch system. This project focuses on creating containerised launchers that can be integrated into various maritime platforms.

The modular nature of such a system would allow even smaller vessels or auxiliary ships to possess a credible counter-drone capability without requiring extensive structural modifications.

Economic and military implications

The estimated cost per unit for the Mark 1 is between $50,000 and $70,000. While this is still a significant cost, it is an order of magnitude cheaper than missiles like the Brimstone or the Patriot. This price point allows for a more favourable ‘cost-exchange ratio’ when engaging drones that may only cost a few thousand dollars themselves.

In comparison, Ukraine’s Wild Hornets ‘Sting’ is a quadcopter-style FPV drone costing approximately $3,000. While the Sting relies on manual piloting for short-range interception, the Micro Mark 1 offers greater speed and fully autonomous AI guidance for infrastructure defence.

From a military perspective, the Mark 1 allows for the preservation of stocks of high-end expensive interceptors. By using the Micro Missile for low-altitude drone threats, commanders can reserve more capable and expensive systems for high-priority targets such as crewed aircraft or cruise missiles.

This creates a tiered air defence architecture that is both more resilient and more economically viable over a long-term engagement.

Future development

The future of the Mark 1 involves continuous refinement of its AI algorithms and seeker technology. As drone technology evolves to become more elusive, the software driving the Mark 1 must be updated to recognise new signatures and flight patterns.

Also, the integration of the missile into broader air defence networks will be essential for ensuring that it can receive initial targeting data from long-range radar systems before its autonomous guidance takes over.

The project demonstrates a shift towards software-defined hardware in the defence sector. Because much of the missile’s capability resides in its algorithms, improvements can be deployed rapidly through software updates rather than through complete physical redesigns.

This flexibility is a core component of the UK’s broader strategy to modernise its armed forces and maintain a technological advantage in a rapidly changing security landscape.

The Micro Missile Mark 1 is a pragmatic response to the realities of contemporary attrition-based warfare. It balances the need for precision with the requirement for mass, providing a tool that is specifically tailored for the most common aerial threats of the current decade.

Let’s hope it fully achieves its objectives and gets into the Ukraine theatre as early as possible. And the way it’s looking right now is that other countries will need them. The European arms industry is sharpening its tools, for sure.

This story was originally published on Medium.

(c) James Marinero 2026. All rights reserved.

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.