An Editor's Guide to Editing Your Novel

A Comprehensive How-To Guide for Self Editing Your Manuscript

Editing your own work is tough—but not impossible.

My name is Rose, and for those of you who don't know me, I'm a professional author and editor. I've written four novels of my own (and countless more, if you consider the ones I haven't published yet) and helped authors bring their manuscripts to the press.

When I first published my series The Afterlight Chronicles, I had a vague idea of what it meant to edit my manuscripts, but I really didn’t understand the intricacies of structural and line editing, nor did I actually put into practice the little bit I did read and learn about. I’ve cut myself some slack for it (after all, I was sixteen when I published the first novel) and have since taken those novels and begun the tedious and tiresome process of self editing to re-release so maybe they won’t be so embarrassing the second time around.

The goal of this post is to educate you (the author) on how to edit your own novel and to save you tons of embarrassment (because shouldn’t an author know the difference between there, their, and they’re?).

So hold on tight, cowboy, because we’re about to dive head first into the world of manuscript editing. And it’s not an easy or exciting voyage.

There are 3 stages to the process of editing:

- Structural or Developmental Editing

- Line Editing

- Proofreading

Of course, you have many different passes and drafts within these stages, but they’re the main types of editing your manuscript will need to undergo before it’s ready to head to print.

Whether you’re planning on sending your manuscript in to a literary agent or you’re publishing on your own, editing your novel it vital. You want to put your best foot forward. I think it’s safe to say that first impressions are everything. If your readers are disappointed in the lack of spellchecking, they’re probably not coming back for more. Likewise, if a prospective literary agent reads your manuscript and finds it full of grammatical issues, inconsistencies, and redundancies? They’re likely not going to pick you up.

Before you start editing, take a week (if not two) and set your manuscript aside. Don’t look at it. Don’t touch it. Don’t think about it.

If you’re going to do this all on your own, you have to be as objective and unbiased as you can possibly be. Fresh eyes only. This is vital to the success of your editing process. As we all know, our brains sort of fill in the gaps if we know the sentence or intention behind the paragraph. We might completely miss the fact that “the” was spelled “teh” the line before because we are just so used to reading that sentence (we wrote it, after all) that our brain fills it in for us.

Give your brain a reset. Don’t touch that manuscript. Be patient. It’s not going anywhere. After a week or two, you’re ready to begin the first step of editing:

Pick up a few books on editing and manuscript style.

Right. That’s not the first stage of editing I mentioned above, but since you’re new to this, it’s important that you at least get the basic concept of what you’re doing.

Books that every editor should have on their desk:

- “The Chicago Manual of Style”

- “Woe is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English” by Patricia T. O’Conner

- “Lapsing into a Comma: A Curmudgeon's Guide to the Many Things That Can Go Wrong in Print--and How to Avoid Them” by Bill Walsh

- “Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation” by Lynne Truss

These are, of course, just a few examples of excellent books to pick up regarding editing/writing style, punctuation, and grammar. The most important of these would be The Chicago Manual of Style.

Now, there are many style manuals that editors may refer to, but The Chicago Manual of Style is probably the most widely-accepted and used. Read it. Memorize it. Love it. It’s your guide to ensuring that everything is cohesive and consistent in your manuscript.

Of course, that’s where books like Woe is I come in. Here, O’Conner recognizes that while English and grammar do have some pretty hard-fast rules, they’re not all unbendable. For instance, the phrase “woe is me.” The correct phrase should be “woe is I,” but no one is going to correct a broadway actor when they deliver that well-known line. It’s been considered good English for generations. As the author so eloquently puts it, “only a pompous twit—or an author trying to make a point—would use ‘I’ instead of ‘me’ here” (O'Conner, 13).

Before you get into the actual editing, pick up these books and at the very least skim them. They’re wealths of information and knowledge and should you need to refer back to them regarding punctuation or grammar, you’ll know vaguely where to look if you’ve read them cover to cover.

So you’ve read the books and taken a couple weeks off? Time to begin editing.

The first thing you want to do when you’re getting ready to start the harrowing process of editing your very own manuscript is to print it off. I know, it’s a terrible waste of paper, but it’s so important. Use recycled paper and print front/back if that helps settle your conscience. It really just isn’t the same on a desktop.

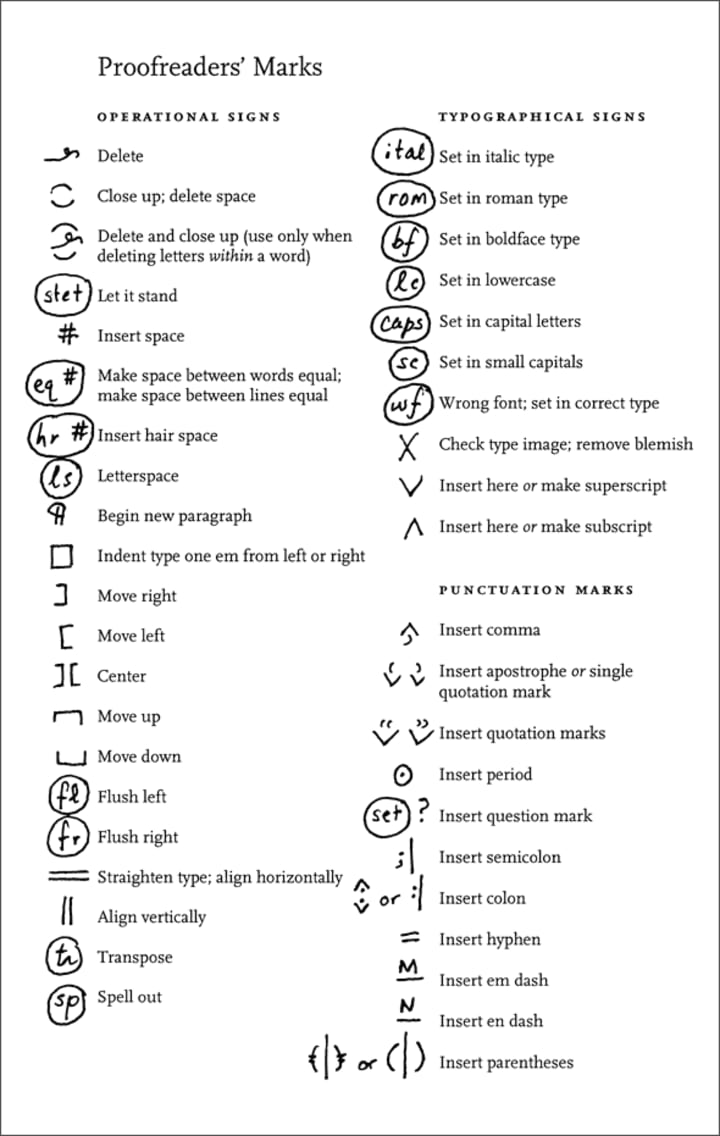

Another good tool to at least take a look at would be the copyeditor’s or proofreader’s marks. If you want to go about things methodically, professionally, and precisely, copyediting marks are an excellent way of keeping track of your own comments and notes.

You don’t have to use these, especially if no one else is going to see your marked-up manuscript, but having a loose understanding of these symbols/marks can help keep things clear and legible on paper.

Structural or Developmental Editing

This is your first stage of editing and it’s probably the most entertaining. It’s also, however, the most difficult.

Put simply, structural/developmental editing is looking at the big-picture story and finding plot holes, character inconsistencies, thematic issues, and similar problems that may arise. Beta readers can be a huge help during this process.

In order to properly edit your manuscript, you’re going to need to have an understanding of the 3 acts and their components (or “beats”). I go into more detail on these beats and acts in my post about my KISS Beat Sheet. However, it’s widely disputed as to whether or not novels actually have a structure like this. I hope it doesn’t seem like taking the fun out of it—in fact, I love it. I think it’s so much better than outlining, as so many suggest.

All you need to know about the acts and beats is this: your novel, regardless of its genre, has a necessary flow. The flow goes like this:

- Hello, world.

- What’s the theme of our world?

- Oh no, something’s happened.

- How are we going to fix it?

- Okay, I’ve got an idea.

- Hey, you’re cute. I think…maybe I like you.

- My idea is working.

- Oh, hell no, it’s not working.

- Wait, I have a better idea.

- I can see it—we’re going to make it!

- Death and despair; the world has ended and the worst thing that could possibly happened…has happened.

- How are we going to pick ourselves back up after this?

- No, we have to do this. For everyone we’ve lost.

- We’ve won! I can’t believe it, but we’ve won.

- Now we have to clean up the mess and live with what’s become of the world.

Obviously, these (very crude) components or beats change slightly depending on your novel, if you have a love interest, or if it’s a series, but the main thought remains the same. There are three acts. There must be a problem and a solution in all three—but no problem as great as the final “death and despair” problem. This should be your “all is lost” moment.

This is where the start of developmental editing begins. Is your manuscript following this flow? Are things hitting at a good time? As you can see, the “death and despair” part is hitting at about 70-75% of the way through the flow. Is that how your manuscript is flowing?

But developmental editing goes beyond the story’s components. When you are structurally/developmentally editing your manuscript, you’ll be looking for:

- Confusing/conflicting/convoluted thematic elements

- Frequency of words (overuse)

- Inconsistencies in characters, plot, locations, dialogue, lore, etc.

- Readability of dialogue

- Confusing elements

- Dauntingly long blocks of paragraphs

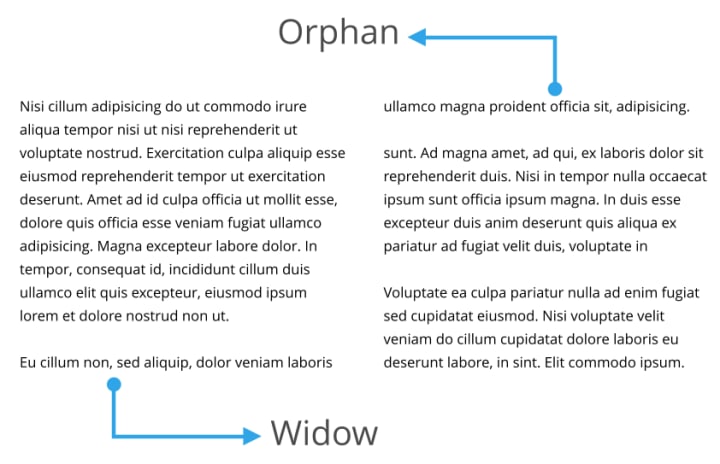

- Widow/orphan lines

- Big-picture issues

- Redundancies

- A choice in style sheet (we’ll get into this)

- Opportunities to better the story, whether this is switching from third-person narrative to first, shortening chapters, combining two characters into one, and the like

Many of these points are self explanatory. For instance, you probably know what I mean by “readability of dialogue.” Others might be a little tricky for a newcomer, so I’ll explain. If you already understand the meaning of all these terms, keep reading…this doesn’t apply to you.

Confusing/conflicting/convoluted thematic elements: You don’t want to have too many themes at play in your manuscript, or themes that conflict with one another. I.e., if your main theme is “money can’t buy happiness,” then you shouldn’t have another theme that seems to imply “money can literally buy you anything.” The same goes for convoluted themes. What I mean by this is that you don’t want to have 8 themes running amuck. The importance of your main theme will be lost.

Frequency of words: It’s natural. I do it, you do it, we all do it. We overuse phrases and words. For instance, I literally just said “for instance” just a couple of paragraphs up. I don’t need to say it again. But it just happens! It’s the first thing that comes to mind. This can occur with words or phrases, so be careful to note these things when you’re doing your structural edit. How many times did you use the phrase, “To each their own,” or “It’s give and take?” Be mindful.

Inconsistencies: I think this is pretty self explanatory but just in case, I’ll go into a bit of detail. An example of character inconsistency might be saying someone has green eyes on one page, then a hundred pages later going on and on about how vivid his deep brown eyes were. For plot, this could mean that the characters needed a USB drive to get into the warehouse, but forget and later say they need a skeleton key or a keycard. You get the gist.

Confusing elements: Have you explained everything well? If you were a new reader, would you know what you meant at all times?

Widow/orphan lines: See below.

You typically don’t want widow or orphan lines in your novel. They look disjointed and can be a bit jarring. Depending on the software you’re using, you can remove these widow/orphan lines with a simple change in the settings. Otherwise, you may have to do some rearranging.

Finally, we have the last one that needs explaining: a choice in style sheet.

A “style sheet” is a manual that dictates the house style of a particular publisher or editor. Good news: you don’t have a publisher or editor, which means this style sheet is made entirely by you, and only you abide by it.

A style sheet is a document where you basically compile all components of your “writing style” so that when you’re editing, your manuscript is consistent. This means punctuation, syntax, and even made-up words.

Example: In my novel Crown of Crimson, I made up a place called the “Afterlight Forest.” Therefore, that term had to be added to my style sheet. It was always capitalized, even when just referring to “the Forest.”

If you don’t have any made-up words, you should still consider creating a style sheet. It’s used for more than just words. This includes your use of em dashes (—), ellipses (…), and the like. Will you be using the Oxford comma?

While you are going through your developmental editing phase, create your style sheet. It’s going to come in very handy when you’re line editing.

Line Editing

Here comes the oh-so-tedious part. This is where you’ll need to be detail-oriented, extremely thorough, and highly attentive. It’s where the majority of the technical editing will be done. Check for spelling, grammatical errors, and other issues in the text.

Line editors get their name because they really go line by line and examine everything. If there is an error? That’s where the proofreader’s or copyeditor’s marks come in. Mark that sucker up and get back to work.

This is also where The Chicago Manual of Style really comes into play. You should check everything that you aren’t 100% certain of.

Is it “I wanted to go there too” or “I wanted to go there, too?”

Seriously. Double check. While Woe is I is right and there are exceptions to these rules, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

For the most part, though, line editing is pretty easy. As long as you can stay focused on the task at hand, remain attentive, and get through the manuscript, you’ll be fine. It’s always good to have another reader (like a friend or relative) go through it one more time to make sure you haven’t missed anything, but you’re probably pretty solid.

Proofreading

Now comes the final phase, and the phase so often neglected. Because writers are often so confident in their line editing, they sometimes ignore the proofreading phase or sort of just blow right through it.

Take the time to go back over your manuscript. It doesn’t have to be as detailed as your line edit, but it should be thorough enough that you catch those little mistakes you didn’t catch before.

Just as you did before you started the editing process, I’d encourage another week or so before you go back through and proofread. It can’t hurt. Delay that deadline—let’s be honest, you shouldn’t have set a release date if it wasn’t ready to go.

Now that your manuscript has been fully edited from developmental to proofreading, you’re ready to head to print!

The best advice I can give to new editors is this: never ease up. If you get lazy, those typos will sneak up on you. Always look at your manuscript with fresh eyes and don’t be afraid to take the time it needs to do the project right. Once it’s out, it’s out. And like we said before, first impressions are everything.

Happy editing!

About the Creator

Rose Reid

professional storyteller. reading lets you escape reality; writing lets you create your own.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.