Tupac’s Truth: Life, Death, and the Fight for a Forgotten Generation

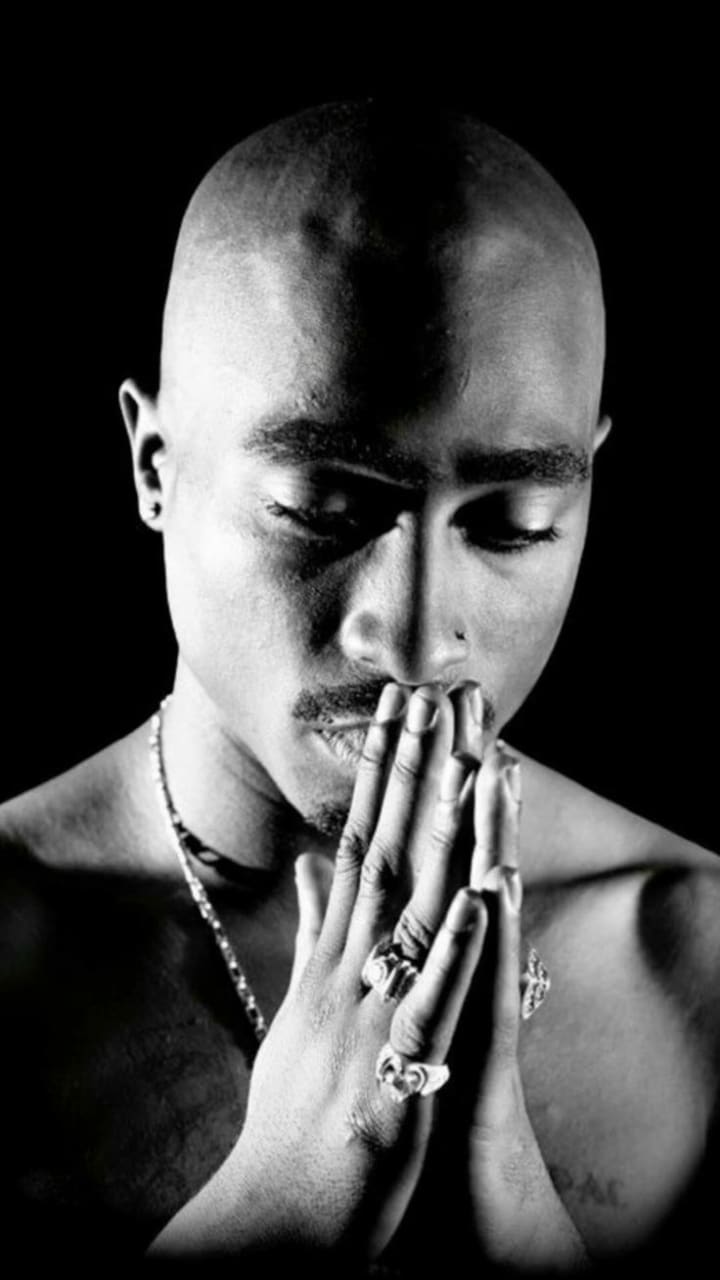

A Rapper’s Unfiltered Voice Rises from the Streets to Demand Respect and Redemption

Imagine stepping out your front door every day, not knowing if you’ll make it back home. Picture a world where the sound of sirens is as common as birds chirping, where the weight of survival presses down harder than any dream of escape. This isn’t some distant battlefield-it’s the reality Tupac Shakur described, a life forged in the crucible of America’s urban underbelly. In a raw, unfiltered conversation, the rapper laid bare the struggles of his generation, painting a vivid picture of a community caught between despair and defiance.

Tupac didn’t mince words. He spoke of neighborhoods stacked with 80 souls crammed into a single building, where stepping outside meant arming yourself-not out of bravado, but necessity. “We live in hell, in the gutter,” he said, his voice thick with frustration. It’s a place where the same police who patrol with rifles and riot gear justify their arsenal for the same reasons residents do: fear of the chaos that lurks around every corner. But while law enforcement dons flak jackets and carries tear gas, Tupac argued, the people they’re meant to protect are left to fend for themselves against the very same threats.

This wasn’t just a lament-it was a call to arms, not for violence, but for unity. Tupac saw his generation as heirs to a fight abandoned by those who came before. “The generation before us forgot about the fight, forgot about us,” he said, his words a mix of accusation and resolve. “We’re picking it back up.” At a time when he had the ears of a million listeners, he recognized the power of that platform-not to preach, but to connect. “We might lose some, we might gain some,” he admitted, “but we’d never have had that audience if we didn’t speak what’s real.”

At the heart of his message was a stark truth: the crime that terrifies white America is the same menace haunting Black communities. “We defend ourselves from the same crime element they’re scared of,” he explained. Yet, proximity breeds a different reality. While others wait for laws to save them, Tupac’s world was “next door to the killer,” a place where killers and victims share the same crumbling stairwells. The idea that Black residents somehow “get along” with the predators in their midst was absurd to him-a stereotype born of ignorance, not understanding.

But Tupac’s story wasn’t just about the streets; it was personal. When asked where he saw himself in a decade, his answer cut deep: “I just want to be alive.” At 23, he’d already faced death’s shadow more times than most do in a lifetime. “I’m not suicidal,” he insisted, “but I can’t die with people thinking I’m a rapist or a criminal.” That fear-of being misjudged, of leaving a legacy tainted by lies-drove him to evolve. “I made a metamorphosis,” he said. “I’m a new person today.” Once indifferent to life, he now burned with a need to set the record straight, to live free and respected, unshackled by the oppression he felt God had cursed him to see.

He saw himself as a soldier in a different kind of war-one fought with words, not weapons. “I feel like I’m doing God’s work,” he declared, contrasting his efforts with those of polished preachers dining with presidents. While others ministered to the middle class, Tupac was in the hood, speaking to kids he believed the world had abandoned. “These ghetto kids are God’s children too,” he said, “and I don’t see no missionaries coming through there.”

His upbringing shaped that mission. Raised without a father, watching his mother-a former Black Panther-struggle, Tupac carried the weight of what could have been. “Had I had a father, I could’ve been a better son,” he reflected, his voice tinged with regret. He didn’t shy away from the pain of that absence, nor the chaos it left behind. “My mother’s my partner, a soldier like me,” he said, recalling her warnings about a world that uses and discards its own. Yet, despite the odds, he dreamed of college-only to be stopped by a lack of money, a barrier that kept him tethered to the streets.

That tether gave him a voice, raw and unpolished, honed by pimps, hustlers, and dealers-his unlikely role models. It was a voice that resonated far beyond the projects, reaching Black, white, and Mexican youth alike. At 23, weighing just 160 pounds, he’d already caught the attention of vice presidents and cops nationwide, all without a grand plan. “I haven’t even started,” he laughed, a spark of defiance in his eyes. “They’re scared, and I haven’t even written it out yet.”

Tupac’s anger wasn’t blind-it was born of clarity. He raged against a society that exiled him, that branded him a threat while ignoring the violence it bred. “I’m tired of waiting for my pass to get in,” he said, rejecting assimilation for pride. That pride, though, came with a cost: anger at being held back, at watching his people suffer. “As soon as a Black man gets his first three checks, he starts getting mad,” he noted, describing a shift from survival to realization-a hunger for more than scraps.

Critics called him a thug, a pawn of record executives cashing in on gangster rap. Tupac saw it differently. “I’m getting pimped, sure,” he conceded, “but who’s really getting pimped?” He pointed to the white kids mimicking his rhymes, their parents footing the bill for a culture they feared. A high school dropout, he was scripting their rebellion-and outlasting the pimps in the process. “The crime isn’t getting pimped,” he said. “It’s how long you let it happen.”

For Tupac, arming himself wasn’t about crime-it was survival. “The media makes you think a Black man with a gun is illegal,” he argued, “but it’s about defending myself.” He refused to pretend the violence didn’t exist, knowing silence would only bury it deeper. “We brought the violence we saw to our records,” he said, forcing a nation to face what statistics alone couldn’t hide. And when stray bullets crossed into white neighborhoods, suddenly everyone cared.

Even as fame grew, danger followed. “I’ve had guns pulled on me by my limo driver, by police, by everybody,” he said, recounting skinhead threats and church bombings. To him, the enemy wasn’t abstract-it was at his doorstep. And while figures like Jesse Jackson criticized rappers, Tupac fired back: “He should support us. We supported him.” Recalling his first acting gig at the Apollo during Jackson’s 1984 campaign, he bristled at the hypocrisy. “He sat there when Martin Luther King caught one in the neck,” he said. “Things haven’t changed that much.”

Tupac’s words were a warning, a plea, a map of a world too harsh for fairy tales. “I don’t got no beautiful stories,” he admitted, but he offered truth instead. His mistakes-forged in a war zone of drugs, loss, and betrayal-became lessons he vowed to share. “I made it past,” he said, “and now it’s my job to stop somebody else from falling.” In a society quick to cheer his downfall, he demanded they cheer louder for his stand-not for his fame, but for his fight. Because in the end, Tupac Shakur wasn’t just surviving. He was shouting for a generation desperate to be heard.

About the Creator

KWAO LEARNER WINFRED

History is my passion. Ever since I was a child, I've been fascinated by the stories of the past. I eagerly soaked up tales of ancient civilizations, heroic adventures.

https://waynefredlearner47.wixsite.com/my-site-3

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.