Workaholic Anonymous

Confessions from a high-functioning executive trapped in a cult of productivity—where every confession is more absurd, darker, and frighteningly familiar.

I never thought I’d be the type to join a support group. In fact, if anyone had told me a year ago that I’d be sitting in a circle of strangers confessing my unhealthy obsession with work, I would have laughed—while scheduling two more meetings before lunch.

But here I am. Workaholic Anonymous. A secret society of people addicted to productivity.

Our meeting place is anonymous enough—a bland community room in an unassuming office park, complete with flickering fluorescent lights and an aroma suspiciously like old coffee and anxiety. The chairs are arranged in a circle, just like every cliché support group movie scene ever portrayed.

The irony is delicious.

I’m a high-functioning executive, a titan of industry—or so I’ve been told. I answer emails at 3 a.m., eat dinner with one hand while closing deals on my phone with the other, and dream about spreadsheets. I am, unequivocally, a productivity machine.

But even machines need maintenance.

Our group leader, Bob, opens the meeting with a sincere yet weary smile. “Welcome, everyone. Remember, what’s said here stays here. Be honest. Be kind. And above all—stay productive.”

It’s unclear if that last part is a joke.

The first confession comes from Linda, a marketing manager who admits she once skipped her child’s birthday party because she couldn’t leave a quarterly report unfinished. “The report was due Monday,” she says, eyes wide, “but I printed it at midnight Sunday. I printed it twice, just to be sure.”

Linda’s story gets nods around the circle.

Next is Raj, a software engineer. “I once spent a weekend debugging code without eating or sleeping,” he confesses. “I lost fifteen pounds, but hey, the feature launched on schedule.”

The group laughs nervously. I recognize the joke; it’s the only one we know.

When it’s my turn, I hesitate.

“I have a confession,” I begin, voice steady but my hands shaking slightly. “I organize my email inbox by color code. It’s not enough that the emails are answered—I need them to be aesthetically pleasing.”

The group murmurs appreciatively.

“But,” I continue, “last week I spent three hours perfecting my calendar. I even deleted appointments that conflicted with my gym time—because I couldn’t face the guilt of not working out while also working.”

There is a collective sigh.

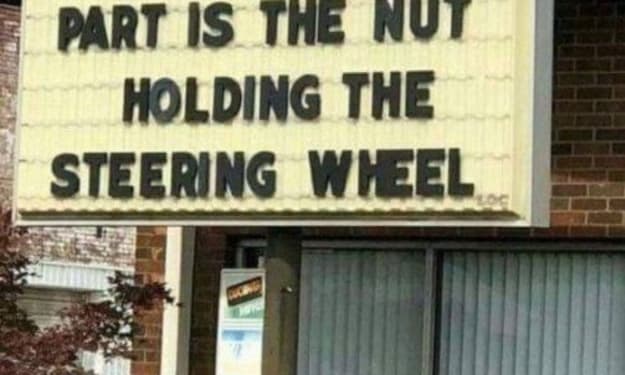

Bob offers a knowing look. “Classic. Guilt is the true CEO of all our productivity.”

Each week, the confessions grow darker—and more absurdly real.

One member admits she schedules bathroom breaks between meetings, as if bodily functions were interruptions in her quarterly profit goals.

Another tells us he’s trained his dog to respond to Slack notifications—because every ping is a summons to action, even in the middle of dinner.

The group shares stories of “productive insomnia,” where sleep is sacrificed at the altar of “just one more email,” and dreams are filled with deadlines and KPI dashboards.

At first, I found humor in the absurdity. Productivity cultists, obsessed with task lists and time-blocking, marching to the relentless beat of efficiency.

But then, I realized it wasn’t just satire.

It was truth.

One evening, after a particularly grueling day of back-to-back Zoom meetings, I sat alone in my apartment surrounded by unopened mail and half-eaten takeout. My phone buzzed—a calendar reminder that I had to “Schedule self-care.”

The irony hit me like a cold splash of water.

I was a man so addicted to productivity that even my self-care was scheduled.

I thought of Workaholic Anonymous and the faces in that circle: Linda, Raj, Bob, and the rest.

People who looked successful, yet trapped in a cycle of exhaustion and self-imposed pressure.

The kind of people who would rather risk a heart attack than miss a quarterly review.

Who measure their worth not by joy or rest, but by the constant tick of the productivity clock.

But here’s the kicker: even admitting the problem was another task on my to-do list.

“To acknowledge your addiction,” Bob said one night, “is step one. But step two is to stop pretending you’re indispensable.”

I nodded, though I wasn’t sure I believed him.

And yet, here’s what I’ve learned from Workaholic Anonymous:

That productivity isn’t just about doing more—it’s about knowing when to stop.

That emails won’t turn to gold if you stare at them longer.

That scheduling self-care doesn’t replace actually caring for yourself.

That life is not a series of tasks to be completed, but moments to be lived.

So now, I try.

I try to close my laptop at a reasonable hour.

I try to savor my coffee instead of drinking it like fuel.

I try to let go of the inbox—just for a moment.

Am I cured?

Hardly.

Am I less of a workaholic?

Maybe a little.

But the real victory?

Knowing I’m not alone.

And that sometimes, the most productive thing you can do…

Is nothing at all.

✨ Final Line:

In a world obsessed with hustle, admitting you need help is the most rebellious act of all.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.