The Word That Couldn’t Translate

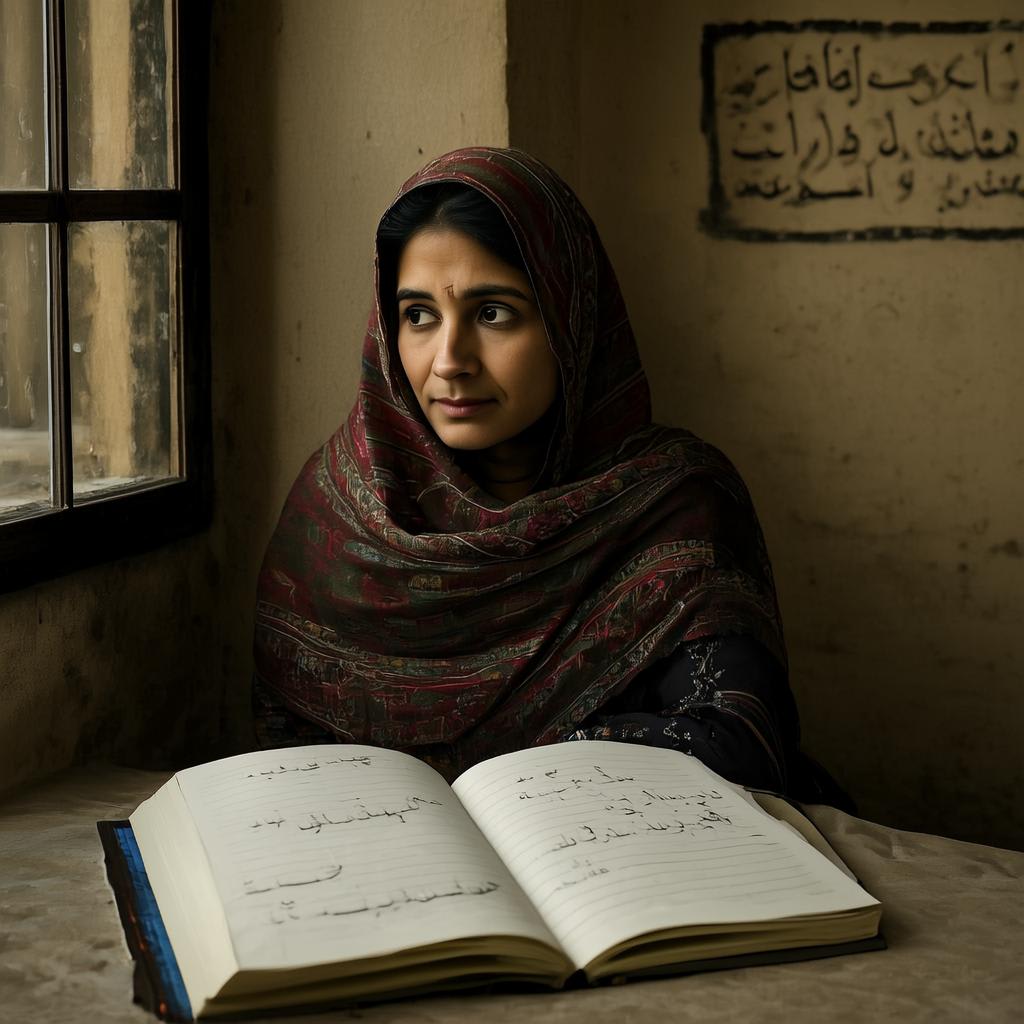

A forgotten Pashto word captures a woman’s deepest sorrow—but the more she tries to explain it, the more it fades. Some grief is only spoken in the language of the soul.

this story create by khalid khan

I first heard the word on a cracked cassette, tucked inside a metal biscuit tin beneath my grandmother’s prayer shawls. The recording was decades old—dusty and halting—her voice steady, deliberate, teaching a little girl how to say a word in Pashto that no one says anymore.

The word was "خفاځئ" (khafāzay).

She said it meant “the ache of something beautiful disappearing too quietly to grieve.” But there was no English word that matched it—not exactly. Not in French, either. Or Farsi. Not even in Urdu, which has always embraced sorrow so poetically.

I wrote it in every notebook I owned. I whispered it while washing dishes, in the steam of the mirror after showers. Sometimes I cried when I said it. Sometimes I smiled. It felt like a map I didn’t know how to read, a home I couldn’t remember living in.

I speak seven languages. I learned some in school, some in books, and some in the bed I once shared with a man from Algiers. But Pashto was my inheritance. And like many inheritances, it was handed to me too late.

When my grandmother passed, I tried to translate her old Pashto letters. Most of the words I could decipher—love, memory, longing. But khafāzay lingered in a different way. It haunted the edges of every phrase, like fog between syllables. When I tried to explain it to others, the word resisted.

“I think it means… regret?” I’d say.

Or: “It’s like nostalgia, but… heavier.”

Or: “Maybe it’s the sadness you feel when a song ends, and you realize you’ll never hear it again the same way.”

Every time I tried, it felt wrong. Not just inaccurate—betraying.

One day, I told the word to a linguistics professor. He nodded thoughtfully and asked me to spell it. I did. He frowned.

“I don’t know this one,” he said. “Maybe it’s a family dialect. Oral languages die like that, you know. Silently.”

His words landed in my chest like stones dropped in a well.

Silently.

I started dreaming in Pashto. Not in full conversations—just fragments. My grandmother’s voice calling me "zama janāna"—my dear one. The hiss of tea boiling. Lullabies without endings.

But khafāzay began slipping away. Some mornings, I couldn’t remember it. I wrote it down again and again, but the shape of it blurred. Was the second letter a ف or a پ? Did the ending hiss like a sigh, or hum like a prayer?

How do you grieve a word?

One night, I sat at my desk and wrote a letter in English, then French, then Farsi. I tried to describe the word without saying it. I filled three pages. Then I burned them.

And finally, I understood.

Some words aren’t meant to be translated.

They are meant to be carried.

Held.

Said aloud before they disappear.

Now, I say khafāzay every time I see my mother braid her hair the old way. When a Pashto lullaby plays in a movie and no one else in the room flinches. When my little niece asks me what language her great-grandmother used to speak.

I say it softly.

Not to explain.

But to remember.

Because even if no one else ever says it again, I will.

And that, maybe, is enough to keep it alive.

Comments (1)

good work