The Rites of Spring

The Spring Fresco of Akrotiri

During our primary education, we are taught science, music, literature, history, and art. We are instructed on what is. Included in this instruction is how the form of things change, like water and its various stages: liquid, solid, and gas. In art, teachers identify certain key contributions as works of art. So, when we are asked the question: "What is art?" we begin listing off types and we may even identify key figures in the art world. These two things, the work of art and the artist, inform us that art is a product of human efforts. By this reasoning, art is anything that we make.

In Preface to Lyrical Ballads", William Wordsworth expresses: "Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." Wordsworth discovered unity and solitude with nature and expressed it through beautiful imagery. More importantly, his work was born of the desire to leave an impression. Wordsworth's poem, "Daffodils" begins: "I wandered lonely as a cloud," giving the reader a sense of isolation and a longing desire to connect.

Noted for its brutality, its barbaric rhythms, and its dissonance, the ballet The Rite of Spring by Russian modernist composer Igor Stravinsky premiered at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris on May 29, 1913. Both Stravinsky and Wordsworth left an impression on their audience and their intent is obvious.

Can the same be said of prehistoric artwork? What was the artist's intent and was there a purpose?

The Spring Fresco of Akrotiri, Thera, since its discovery in 1967, has been a topic of consideration for both archaeologists and art historians. This colorful fresco covers three walls of a private room in a prehistoric dwelling, depicting a rugged landscape and volcanic rocks, swallows, and calla lilies. Literature, music, and the visual arts provide a vast collection of works whose main subject matter has been nature, and in this case, the landscape of spring. This paper will identify the culture of the region and its history, complete a visual analysis of the Spring Fresco, and will compare the imagery of this fresco to others found in Akrotiri, Thera.

Background

The Spring Fresco is an example of a “nearly intact Aegean Bronze Age wall painting found in situ” in Akrotiri, one of the Aegean's most significant and advanced prehistoric settlements. Located on the island of Thera, commonly known as Santorini, Akrotiri prospered for centuries before being buried by meters-thick layers of volcanic ash and pumice in the middle sometime between 1650 and 1550 BCE. In 1989, Mary B. Hollinshead wrote that

Archaeological evidence indicates that all the paintings associated with the artist [who rendered the Spring Fresco] were produced after a major earthquake, as part of the reconstruction and redecoration of the town of Akrotiri.

While the reconstruction and restoration were underway, the town was devastated by the volcanic eruption that most archaeologists believe basically blew open the middle of the island, leaving an underwater caldera (crater) and leaving the island in its now crescent shape. Some geologists believe that this may have been the largest eruption in the past 5,000 years. Just like in Pompeii, a town on the island of Santorini, or ancient Thera, Akrotiri, was preserved under layers of volcanic ash and pumice. However, the site was not discovered before modern archaeological techniques had been developed, whereas Pompeii incurred extensive damage by people who were removing art as trophies.

The cultures of the Grecian Bronze Age include the Cycladic islands, the Minoans of Crete, and the Mycenaeans of the mainland of Greece. The Bronze Age lasted approximately three thousand years, making significant strides in social, economic, and technological advances, ultimately becoming the center of all trade, fishing, and activity in the Mediterranean. It is important to note that for many years historians and archaeologists believed that these cultures were separate and distinct. And that the people in Akrotiri did not have any relationship with either the Mycenae or the Minoans. However, over time, they have concluded that these cultures were very much intertwined. And since the discovery of the lost city of Akrotiri, many have come to the conclusion that Akrotiri was directly related to the Minoan culture and may have been under the control of Crete. The frescoes from the Aegean Bronze Age found in Akrotiri are evidence of the Minoan influence. Due to archaeological evidence, we also know that the Therans traded with the Myceneans. These discoveries are due in part to the protected excavations at Akrotiri and the systematic process of uncovering and studying the remains of Akrotiri.

Visual Analysis - Nature

Often, when we examine works of art we ask ourselves: “Why was this work created?” Without explicit evidence from the artist, such as a written record, we are left with the interpretations of art historians and archaeologists (possibly anthropologists). In his essay ”The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” Erwin Panofsky shares his ideas about why an artist creates art. Interestingly, the artistic intention does not reside with the work of art, rather, according to Panofsky

our estimation of those ‘intentions’ is inevitably influenced by our own attitude, which in turn depends on our individual experiences as well as on our historical situation.

As a result, any interpretation of the artist’s intention is subject to the art historian's personal views and aesthetics. Panofsky suggests that these should be weighed against historical and iconographic evidence. In order to give a thorough examination of the Akrotiri Spring Fresco, this paper will focus on what is known and what is observable.

The first thing we know about the Spring Fresco is that it is a true fresco painting, also known as buon affresco. Britannica defines

Buon', or “true,” fresco [as] the most-durable method of painting murals, since the pigments are completely fused with a damp plaster ground to become an integral part of the wall surface.

It is a technique that incorporates pigments, usually mixed with water, onto wet plaster:

Paints were derived from minerals to provide strong colours such as red, orange, black, blue, purple, and white, and organic material was used as a fixative.

After the plaster and pigments have dried, the paints literally become a part of the wall. In the case of the Spring Fresco, this is a wet painting over a fine layer of plaster over a rougher layer of plaster, over straw. It is also important to note that this mural is also a landscape painting, a representation of natural surroundings. The natural surroundings of Akrotiri, Thera likely contained lilies, swallows, and volcanic rock, as depicted in the Spring Fresco; one of the earliest examples of landscape paintings. Landscapes - and seascapes - are key elements of many of the mural paintings found at Akrotiri. In each case, however, the artist’s aim was not to render the rocky island terrain realistically but rather to capture its essence.

In discussing “Dialogues between the Environment and Art” Irina D. Costache states that

One of the most frequent interactions between the environment and art is the subject matter. The landscape has been widely depicted in art. Artists have reflected upon their surroundings in a variety of realistic, idyllic, or conceptualized depictions.

It is not a landscape in the traditional sense with fields, trees, and sky. It is a likeness, rather than a true or accurate depiction. Stephen Perkinson would state that “the concept of likeness is deeply tied up with the act of representation through images” and the Spring Fresco is doing just that. The imagery is abstract and stylized, however, the lilies, swallows, and volcanic rock are easily recognizable. Keith Branigan shares that during the

Bronze Age the Cyclades and Crete (Minoan) developed their own distinctive art and architecture, in each case strongly influenced by the islands’ natural environment.

The volcanic rocks inhabit the lower third or foreground of the mural and are depicted as curvilinear forms. The colors blue, red, and yellow are representative of the different colors of the volcanic earth found on Thera. These colors were also commonly used in Theran fresco paintings. The middle ground is occupied by the abstracted renderings of lilies and swooping swallows. Mary B. Hollinshead gives a beautiful description of this scene:

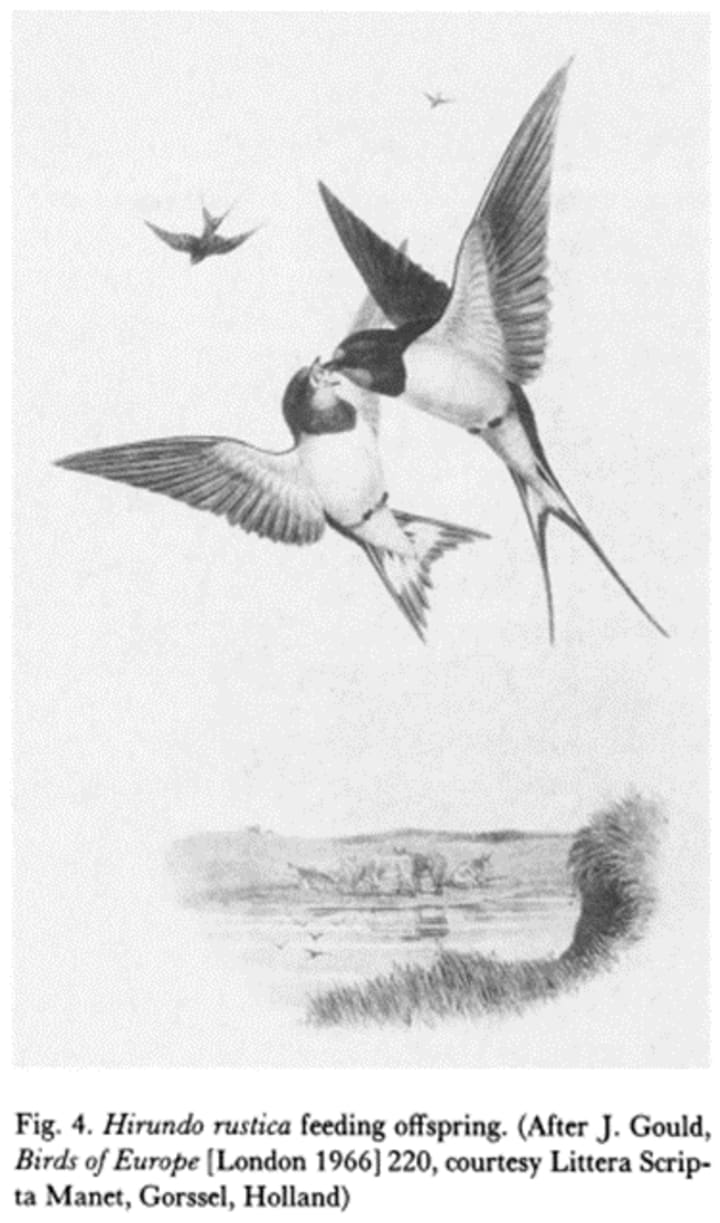

Flying among and above the oversize[d] red lilies, alone or in pairs, the swallows are rendered simply, in spare sweeping strokes. The shape of their wings and the two-pronged tail identifies them as hirundo rustica rustica, The European swallow, a close relative of the North American barn swallow (hirundo rustica erythrogaster). The artist has taken care to show the species’ diagnostic plumage, with dark upper body, pale lower parts, and red throat and forehead.

The yellow in place of green for the foliage is topped by blooms of red in various stages. Following the curvilinear patterns of the foreground, the swallows are formed with simple marks using a blue-gray pigment. And in place of the sky, the white plaster fills in the space.

There are repeated themes found in the Spring Fresco that appear in other Minoan/Theran artwork. According to noted archaeologist Nanno Marinatos, flowering plants, birds, and animals are significant iconography found in the Minoan religion:

For a Minoan or Theran, a painting represented part of his tradition which was comprehensible and even predictable. It can be said that art was a representation of the collective values of the society of which the viewer was a member. Thus, the relationship between art and viewer was intimate and the function of the painting important...the themes centred around religious experiences, although these could be indirect as well as direct. Political portraiture seems to be totally absent.

Anne P. Chapin discusses this significance in “Power, Privilege, and Landscape in Minoan Art:” stating that

The crocuses and lilies … appear consistently in Aegean art as offerings and as decorations for altars and offering tables.

Interestingly, A little over twenty years after the discovery of the Spring Fresco, Mary B. Hollingshead states:

The red lilies are seen as potentially significant, but not necessarily predictive of a religious function… Instead of a naturalistic setting for cult practice, Delta 2 is best understood as a safe and aesthetically pleasing environment for an important person.

Later in her discussion, she concludes that the space was primarily for sleeping. Others, like Karen Foster, disagree with this determination. Because of the religious themes of the lilies and the swallows set in a small, darkened room, there is conflict over the purpose of the room. Chapin wraps up this discussion by stating that

so little is known about what constitutes sacred, domestic, and public space in Aegean prehistory that it is difficult to establish objective criteria for characterizing Delta 2 as a cult room.

As Keith Branigan points out about the cultures of the Cyclades and the Minoans, the art and distinctly the frescoes are heavily influenced by the natural environment. Whether the fresco was created for private use or as a backdrop for religious ritual, the Spring Fresco is a representation of the things that the culture and society valued. At the end of the day, we may not be able to answer whether the naturalism depicted in this fresco carries any meaning beyond aesthetics.

Comparative Analysis

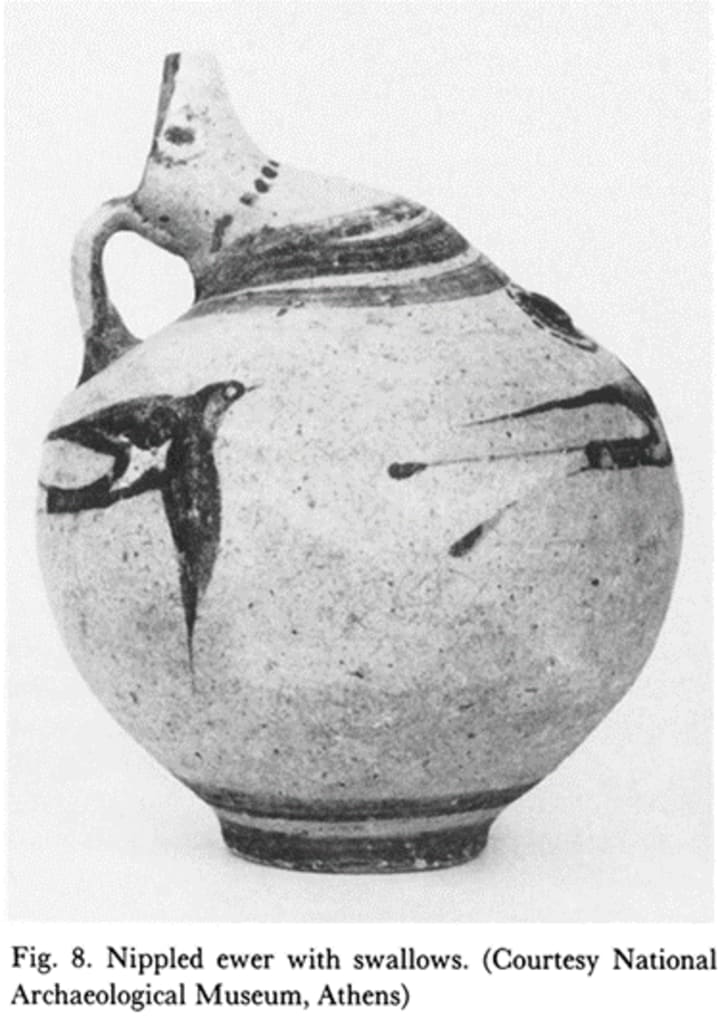

The Spring Fresco is known for its three main attributes: rocky terrain, blooming lilies, and the flying and swooping swallows. Hollinshead observes that the “Swallows are a recurrent, characteristic motif on pottery found at Akrotiri.” One example of this is the breasted ewer with painted bird motif, also from Akrotiri, Thera. There are some minor differences between the Spring Fresco and the breasted ewer. The fresco depicts the swallows outlined in black with the rest of the body filled in with white, and the tail is elongated. The ewer is similar in the shape of the swallow, however, both wings are filled in with black and the neck is red. The ewer provides a more distinct representation of the swallow, whereas the fresco is abstract and emphasizes the movement of the birds in flight through the use of exaggerated curves, and elongated wings and tails. According to Keith Branigan, et al:

During the two early phases of the Late Cycladic (LC) period Minoan vases were imported from Crete and imitated to a remarkable extent. Minoan teacups, Vapheio cups and bridge-spouted jars were typical shapes, and , as in Crete, many of the decorated motifs were floral or vegetable. Spirals were also common.

An indication that Akrotiri was heavily influenced by Minoan Crete. In addition, the frescoes of Akrotiri have marked similarities to the frescoes in Crete. The Cycladic wall paintings discovered at the excavation sites on Thera, Melos, and Kea

have revealed towns with wall paintings that clearly owe much to Minoan painting on Crete yet have distinctively local characteristics.

One of the distinct differences between the wall paintings found in Crete and any of the Cycladic frescoes is the structures with adjoining rooms with a series of related paintings. As is the case with the fresco paintings found in Akrotiri. In addition, unlike Minoan Crete, the Cycladic frescoes seemed to switch between images of cult activity and that of the natural world. However, the themes of life, nature, and culture were shared by both. Branigan adds: “every house or house-complex had a painted room,” another significant distinction between the frescoes of Akrotiri and Minoan Crete, where frescoes were in palaces.

Besides swallows, the Spring Fresco contains red lilies in different stages of bloom. As mentioned early and supported by Branigan, “lilies were associated with cult in Aegean iconography” and so were large papyrus plants. “Room of the Ladies,” located in the “House of the Ladies,” also contains fresco paintings. And much like the Spring Fresco, the mural covers three walls with representations of papyrus flowers in groups of three. Interestingly, the papyrus flower is not indigenous to Thera, and the iconography is Egyptian in nature. Other frescoes in Akrotiri depict blue monkeys, boxing boys, antelopes, and women dressed in Minoan attire gathering saffron. Nature is a pretty important part of the culture at Akrotiri. Sometimes this nature was associated with ritual, however, there are many that don’t have a direct connection to religious practice. Branigan suggests that the paintings may:

reflect Cycladic religious beliefs, which must have revolved around the relationship between humans and the natural world. Even apparently pure nature scenes, such as the Spring fresco, relate to a specific time of year of crucial importance in the cyclical life of those dependent on their environment.

The relationship between humans and nature has been documented throughout history in poetry, literature, music, and the visual arts. Whether flowering papyrus, blooming lilies, or dancing daffodils, the imagery represents our desire to connect with nature. The Spring Fresco landscape depicts the natural environment of Thera and the connection that the people of Akrotiri had with that environment.

References

Branigan, Keith, C. D. Fortenberry, Lyvia Morgan, R. L. Barber, Christos G. Doumas, Updated and Plantzos, Dimitris Plantzos, P. M. Warren, Reynold Higgins, and J. Lesley Fitton. “Cycladic.” Oxford Art Online, February 24, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t020787.

Cartwright, Mark. "Akrotiri Frescoes." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified March 27, 2014. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/673/akrotiri-frescoes/.

Chapin, Anne P. “Power, Privilege, and Landscape in Minoan Art.” Hesperia Supplements 33 (2004): 47–64. https://doi.org/http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354062.

Costache, Irina D. “Dialogues between the Environment and Art.” Essay. In The Art of Understanding Art, 22–37. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012.

Hollinshead, Mary B. “The Swallows and Artists of Room Delta 2 at Akrotiri, Thera.” American Journal of Archaeology 93, no. 3 (July 1989): 339–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/505585.

Marinatos, Nanno. Art and Religion in Thera: Reconstructing a Bronze Age Society. Editions Souanis Bros Company, 2014.

Panofsky, Erwin. “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline.” Introduction. In Meaning in the Visual Arts, Phoenixed., 1–25. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Perkinson, Stephen. “Likeness.” Medieval Art History Today - Critical Terms, Studies, in Iconography 33 (2012): 15-28.

Ray, Michael. “Fresco Painting.” Edited by Alicja Zelazko. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., December 22, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/art/fresco-painting#ref136952.

Schwarm, B.. "The Rite of Spring." Encyclopedia Britannica, May 8, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Rite-of-Spring.

Wordsworth, William, and Owen Warwick Jack Burgogne. Wordsworth's Preface to Lyrical Ballads. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1957

About the Creator

Rebecca A Hyde Gonzales

I love to write. I have a deep love for words and language; a budding philologist (a late bloomer according to my father). I have been fascinated with the construction of sentences and how meaning is derived from the order of words.

Reader insights

Good effort

You have potential. Keep practicing and don’t give up!

Top insights

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.