The Obsolete Industry Dilemma

What If the World Stopped Inertia-Production for One Year?

The Obsolete Industry Dilemma: What If the World Stopped Inertia-Production for One Year?

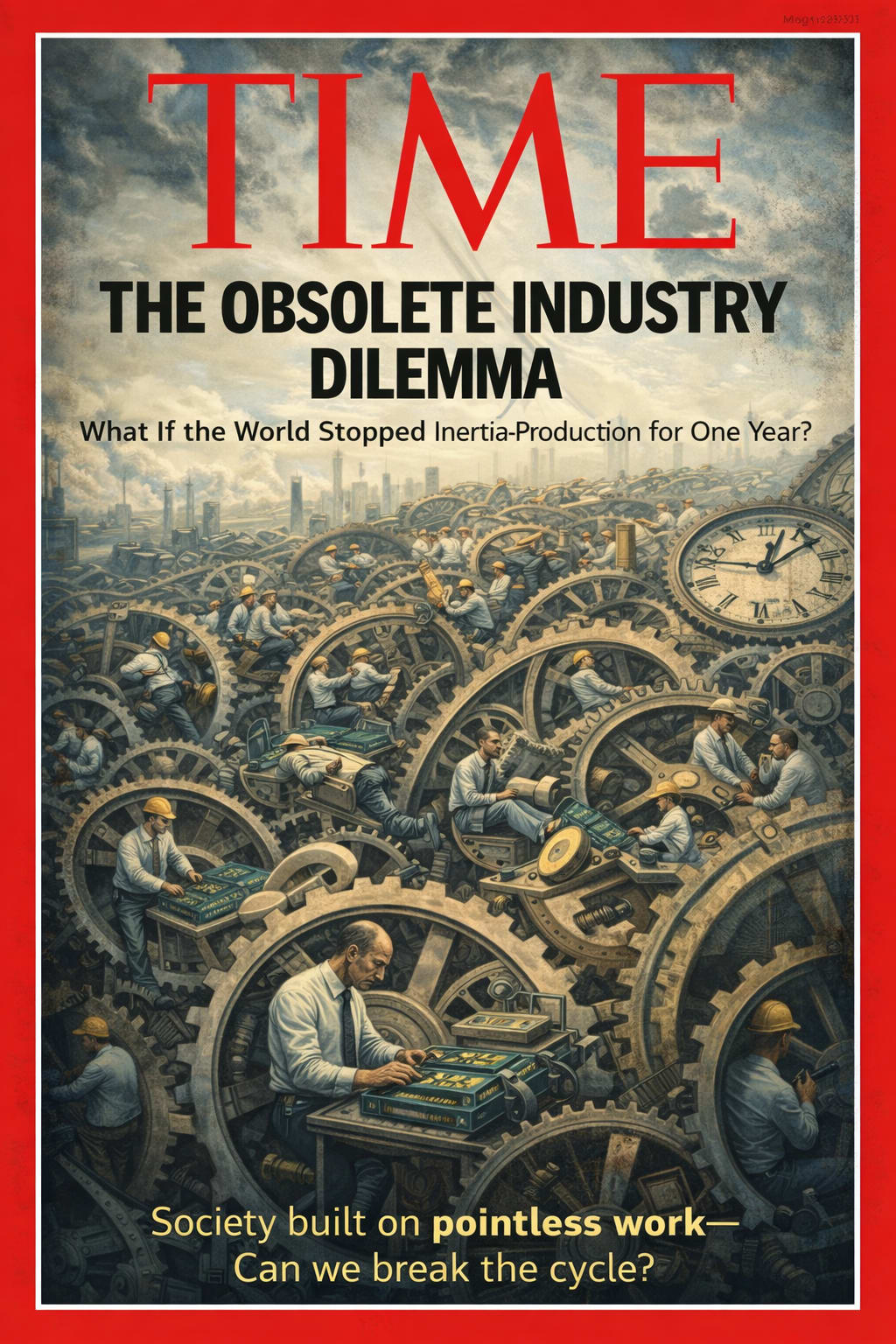

Imagine not a technological breakthrough, not a green miracle, but a simple interruption. For one year, the world stops inertia-production: the endless manufacture of goods, services, movements, and institutions that persist not because they are needed, but because stopping them would expose how deeply human life has been reorganised around motion without purpose. This is not merely a pause in car production or construction or transport. It is a pause in the logic that turns people into components, societies into mechanisms, and the planet into an enormous clockwork Earth, rotating endlessly through repetition, habit, and systemic momentum.

Inertia-production is production that continues because it already exists. It is not driven by human need, ecological necessity, or cultural meaning, but by the self-preserving logic of systems. Cars are produced because factories must run, factories run because supply chains exist, supply chains exist because finance demands throughput, and finance demands throughput because stagnation would reveal that much of this activity no longer serves life at all. The same logic governs pointless travel, redundant offices, empty buildings erected as “investments”, and entire industries whose sole function is to manage, regulate, insure, advertise, or legitimise other unnecessary industries.

The automotive example makes this visible because it is measurable. Each year, roughly ninety million cars are produced, each embedding a vast amount of energy, materials, and emissions. Retrofitting existing vehicles instead of replacing them would avoid hundreds of millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide, an amount comparable to global aviation emissions in an average year. Consumers would collectively retain trillions of dollars otherwise absorbed by new production. The planet would gain time. People would gain resources. And yet the system would experience this as catastrophe.

But cars are only a symptom. Inertia-production extends far beyond manufacturing. It includes the daily circulation of people between home and work even when the work could be done elsewhere or need not exist at all. It includes logistics chains moving identical objects across continents to satisfy accounting efficiencies rather than human logic. It includes the construction of buildings designed to be occupied by capital rather than people, standing empty yet demanding energy, maintenance, and administrative oversight. Each layer generates further layers of activity, creating a self-reinforcing loop of motion that appears as progress while producing little of lasting value.

Within this loop, people increasingly resemble machine parts. Jobs are structured as repetitive gestures within larger systems no one fully understands or controls. Tasks are performed not because they matter, but because they must be performed to keep the system turning. Individuals rotate through schedules, meetings, platforms, and metrics like cogs in a planetary mechanism, repeating the same movements day after day, year after year. The system does not require creativity, judgment, or meaning; it requires compliance, continuity, and the maintenance of rhythm.

This is the human cost of inertia-production. As David Graeber observed, “bullshit jobs” are not merely inefficient; they are psychologically corrosive. They force people to simulate purpose while knowing, often subconsciously, that their labour has no real causal impact on the world. The result is burnout without exhaustion, anxiety without danger, depression without tragedy. People are not overworked in the classical sense; they are over-rotated, spun endlessly within systems that cannot explain why they exist.

If inertia-production were interrupted, even temporarily, the first effect would be shock. Factories would slow, offices would empty, schedules would dissolve. The machine would stutter. But the deeper effect would be existential. Millions of people would suddenly be released from roles that required them to act as components rather than agents. The immediate question would not be economic but ontological: who are you when the system no longer needs you to turn its wheels?

This is where the political dimension emerges. A society organised around inertia-production governs through employment, hierarchy, and dependency. Remove the need for constant motion, and the legitimacy of this order collapses. New forms of organisation would be unavoidable, not as ideological experiments but as functional necessities. Universal basic income would cease to be a moral debate and become a stabilising mechanism, allowing people to exist without performing meaningless labour. Value would detach from productivity metrics and reattach to care, participation, learning, and contribution to shared life.

Mental health would sit at the centre of this transition. Economic security reduces stress and anxiety, but the deeper challenge would be meaning. Work has long functioned as a surrogate for purpose, identity, and social belonging. Its disappearance would initially create a void. Yet voids are also spaces. Freed from repetitive motion, people could rediscover forms of activity that are ends in themselves rather than means to systemic survival: art, play, craft, conversation, attention.

Culture would shift accordingly. Art would no longer be required to decorate empty buildings or justify urban regeneration schemes. It could return to its older function as a shared symbolic practice through which societies interpret themselves. Sports and games would lose their hyper-professionalised spectacle and regain their communal, bodily, and playful dimensions. Progress would no longer be measured by throughput but by depth: of experience, of relationship, of understanding.

Childhood would perhaps be the most visibly transformed. Education would no longer serve primarily as training for insertion into the machine. Learning could focus on curiosity, cooperation, and imagination rather than future employability. Families would no longer be forced to organise life around schedules designed to optimise productivity. Time, reclaimed from inertia-production, would reappear as a human resource rather than a scarce commodity.

The comparison with *The Gods Must Be Crazy* is instructive. In the film, a single object from industrial civilisation—a Coca-Cola bottle—disrupts a previously stable social world by introducing desire, hierarchy, and conflict. Eventually, the object must be discarded to restore balance. In modern societies, inertia-production has multiplied that bottle into millions of forms: cars, buildings, jobs, metrics, and routines that demand allegiance without offering meaning. The dilemma is whether humanity can let go of these objects without first mistaking them for gods.

Stopping inertia-production for one year would not create utopia. It would create a reckoning. The world would discover how much of what it calls progress is simply movement sustained by habit, fear, and institutional self-preservation. The real question is not whether the system could survive such a pause. It is whether human life can continue indefinitely as a set of rotating parts inside an ever-accelerating machine.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.