The Key Without a Lock: The Librarian, the Lifer, and the Alphabet of Redemption

In the brutal hierarchy of San Quentin, weakness is a death sentence. For thirty years, a gang enforcer named Raymond Cortez hid a secret that terrified him more than the guards or the rival gangs. It took a quiet woman with a stack of children's books to dismantle the lie he lived in

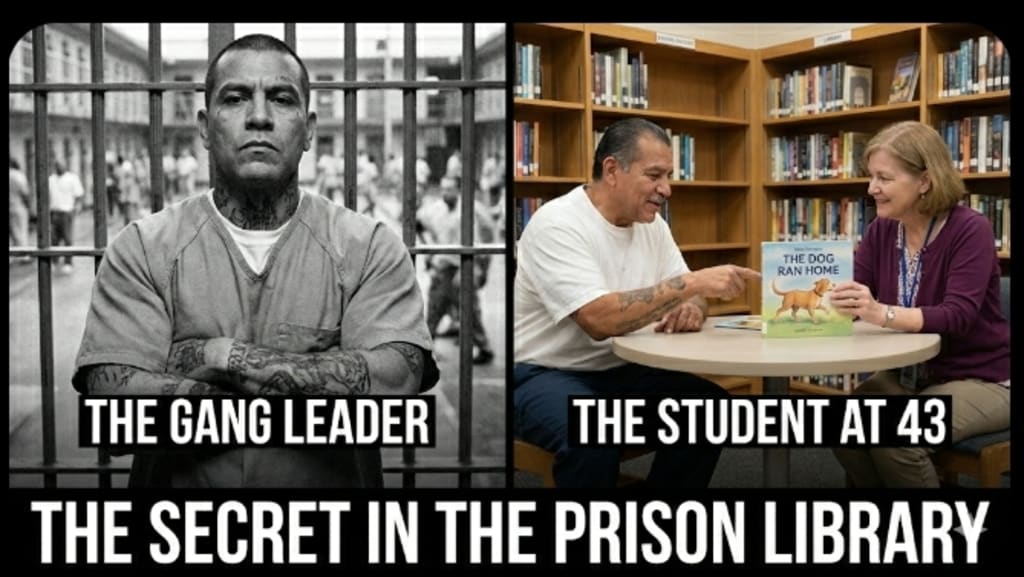

The moving true story of Elaine Thompson, a prison librarian at San Quentin, who taught illiterate inmate Raymond Cortez to read at age 43, transforming a violent life through the power of literacy.

Introduction: The Loudest Place on Earth

San Quentin State Prison is a universe of noise. It is a cacophony of slamming iron, shouting men, blaring radios, and the constant, grinding friction of thousands of souls packed into concrete cages. It is a place where silence is suspicious. Silence means someone is plotting, or someone is bleeding.

But there is one room where the noise stops.

Tucked away in the education wing, past the checkpoints and the metal detectors, sits the library. It is a small, windowless room that smells of dust and old paper—a scent that does not belong in a place that smells of sweat and industrial cleaner.

In 2009, this room belonged to a woman named Elaine Thompson.

Elaine was not a "prison reformer" in the Hollywood sense. She didn't march in with big speeches about saving souls. She was a librarian. She was middle-aged, wore practical shoes, and possessed a quiet, steely patience that had survived twenty years in the state correctional system.

She was invisible to the wardens. She was invisible to the media. And for the most part, she was invisible to the men. Most inmates came to the library for legal forms or to sleep in a quiet corner.

But one day, a man named Raymond Cortez walked in. And he didn't want to sleep.

Part I: The Mask of the Enforcer

Raymond Cortez was 43 years old. He had been in the system, on and off, since he was a teenager. He was serving three consecutive life sentences.

In the ecosystem of the yard, Raymond was a "heavy." He was a shot-caller. He was a man you asked for permission before you walked down a certain tier. He had survived decades of gang warfare by being smarter, faster, and more ruthless than the man standing next to him.

But Raymond Cortez lived in a state of constant, paralyzing terror.

It wasn't fear of a knife in the ribs. It was fear of a piece of paper.

Raymond Cortez could not read.

He had dropped out of school in the third grade to run the streets. For thirty years, he had navigated the world through a complex system of deception and memory.

He memorized the logos on food packages.

He recognized the shapes of street signs.

In prison, he developed a "mask." When the mail came, he would hold the letter, stare at it, nod knowingly, and then later, in the privacy of a cell, he would trade a soup or a pack of cigarettes to a cellmate to read it to him.

"My eyes are bad, homie. The light in here gives me a headache. Read this for me."

It was a brilliant performance. But it was exhausting.

In prison, knowledge is power. Illiteracy is dependence. And dependence is the ultimate weakness. If you have to ask another man what your lawyer sent you, that man owns you.

Raymond had built a reputation of violence to protect a core of shame. He hit people so they wouldn't get close enough to see that he couldn't decipher the tattoo on his own arm.

Part II: The Request

On a Tuesday in 2009, the mask slipped.

Raymond wandered into the library. He walked up and down the aisles, looking at the spines of the books. To him, they were just colored bricks with gibberish written on the side.

He stopped at a shelf of oversized books. He pulled one out. It had a picture of a 1960s muscle car on the cover. He stared at the picture.

Elaine Thompson was shelving books nearby. She saw him. She saw a man who looked like he could snap a baseball bat in half, holding a book like it was a delicate bird.

He looked up and saw her watching him. He froze. The instinct to posture, to intimidate, flared up. But then, something broke.

He walked over to the desk. He didn't make eye contact. He pointed at the book.

"Which one of these books..." his voice was a gravelly whisper. "Which one of these is about how to fix engines?"

Elaine looked at the book. It wasn't a manual. It was a pictorial history of Detroit.

She looked at Raymond. She looked at his hands, scarred from years of fighting. She looked at his eyes, which were darting around the room to see if anyone was listening.

A lesser person might have said, "That's a history book, the manuals are over there."

A judgmental person might have said, "Can't you read the title?"

Elaine Thompson did neither. She realized, with the intuition of a lifelong educator, that he wasn't asking about engines. He was confessing.

"I can show you," she said softly. "But the best books on engines... you have to read the instructions."

Raymond looked at his boots. "I can't."

The words hung in the air. A confession of weakness that, in the yard, would have cost him his rank.

Elaine didn't blink. She didn't smile in that pitying way that Raymond hated. She just nodded.

"If you come here every day for twenty minutes," she said, "I will teach you."

Part III: The Secret Classroom

They made a deal. It had to be secret. If the other inmates knew the "Shot Caller" was learning his ABCs, he would be a laughingstock. Or a target.

Elaine set up a spot in the back corner of the library, behind a stack of tall shelves. It was a blind spot to the rest of the room.

The next day, Raymond arrived.

Elaine didn't start with Moby Dick. She started with a book designed for a five-year-old.

It is a profound humiliation for a grown man—a man who has survived riots and solitary confinement—to sit in a small chair and stare at a picture of an apple and the letter 'A'.

The mechanics of reading are physical. Your mouth has to learn shapes it has never made. Your brain has to connect a squiggly line to a sound.

For the first week, Raymond sweat through his shirt. He was frustrated. His hands shook.

"I can't do this," he hissed, slamming his hand on the table. "I'm too old. My brain is cooked."

"Your brain is fine," Elaine said calmly. "You memorized the hierarchy of a gang. You memorized the layout of this prison. You have a memory. We just need to give it a code."

She was relentless. She was kind, but she was strict. She treated him not as a prisoner, but as a student.

She hid the children's books inside copies of National Geographic so that if anyone walked by, it looked like Raymond was just looking at maps.

Part IV: The Dog Ran Home

Three weeks in. The moment.

Elaine placed a sheet of paper in front of him. It had a simple sentence. Four words.

Raymond stared at it. The squiggles stopped dancing and stood still. He took a breath. He made the sounds.

"The... duh-og... dog."

He paused.

"Ra-nn... ran."

He paused again.

"Ho-mm... home."

The dog ran home.

It wasn't Shakespeare. It was a sentence about a dog.

But Raymond stopped. He looked at Elaine. Then he looked back at the paper. He read it again, faster.

"The dog ran home."

He put his head down on the library table, buried his face in his arms, and began to sob.

He didn't cry like a man in pain. He cried like a man who had been holding his breath for forty years.

Elaine sat quietly. She didn't touch him. She just let him weep.

He wasn't crying because of the dog. He was crying for the wasted years. He was crying for the little boy in the third grade who had been called stupid and believed it. He was crying because, for the first time in his life, a piece of the world made sense to him without him having to fight it.

"I read it," he choked out. "I read it."

Part V: The Rewiring of a Mind

Once the door was cracked open, Raymond kicked it down.

He became voracious. The twenty-minute sessions turned into hour-long sessions. He stopped going to the yard. He stopped hanging out with the gang. He was in the library.

He went from The Cat in the Hat to The Outsiders.

From The Outsiders to Of Mice and Men.

Steinbeck hit him hard. He understood Lennie. He understood George. He understood the dream of a piece of land that you can never quite reach.

Then he moved to non-fiction. He read The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

This was the turning point. Malcolm had learned to read in prison, copying the dictionary page by page. Raymond saw himself in that story. He realized that his anger—the rage that had fueled his violence for decades—was actually frustration. It was the screaming of a mind that had no language to express itself.

"I used to hit people because I couldn't tell them what I was feeling," he told Elaine one day. "I didn't have the words. So I used my fists. Fists are a language, but it's a limited vocabulary."

As his vocabulary grew, his aggression shrank. The guards noticed. The "Shot Caller" was quiet. He was walking differently. He wasn't posturing. He was thinking.

Elaine watched this transformation from her desk. She saw the man physically change. His face softened. The tension in his jaw relaxed.

He wasn't just learning to read words; he was learning to read the world.

Part VI: The Letter

In 2014, five years after he first walked into the library, Raymond came to the desk with a piece of lined paper and a pen.

"I need an envelope," he said.

"Who are you writing?" Elaine asked.

"My daughter."

Raymond had a daughter. She was 26 years old. He had been in prison for most of her life. They spoke on the phone occasionally, awkward, stilted conversations. He had never written to her. He couldn't.

He sat down and wrote. It took him two hours. He checked the dictionary constantly. He asked Elaine about commas.

Dear Mija,

I hope this letter finds you well. I am writing to you myself. I want to tell you that I am sorry for the time I missed. I am reading a book called Les Misérables. It is about a man who tries to become better. I am trying too.

He mailed it.

A week later, he got a letter back.

His daughter had framed his letter on her wall. She told him that she had sat on her floor and cried when she recognized his handwriting—shaky, childlike, but his.

"That is the first time," she wrote, "that my father ever truly spoke to me."

Raymond carried that letter in his pocket every day. It was worth more to him than all the street cred in California.

Part VII: The Quiet Departure

Elaine Thompson worked at San Quentin for a few more years. Then, she retired.

There was no ceremony. The warden didn't give a speech about how she had rehabilitated a gang leader. The news cameras didn't show up.

She packed her bag, returned her keys, and walked out of the gate.

She left behind a library that was exactly the same as she found it.

Except for one thing.

Raymond Cortez was still there. He was still serving a life sentence. He would likely die in prison.

But he was no longer just an inmate.

Raymond had started a program. Informal at first, then tolerated by the guards. He gathered young inmates—the 19-year-olds who came in acting tough and illiterate, just like he had been.

He sat them down in the back corner. He opened the children's books.

"Don't be ashamed," he would tell them. "I didn't learn until I was 43. But once you learn, they can't lock your mind up anymore."

Conclusion: The Freedom of the Mind

We talk endlessly in America about "Criminal Justice Reform." We talk about policies, and funding, and recidivism rates.

But we rarely talk about the specific, granular tragedy of illiteracy.

60% of the US prison population is functionally illiterate. 85% of all juveniles who interface with the court system are functionally illiterate.

We lock men in cages for acting like animals, but we never taught them the tools to be fully human. Language is the software of the soul. Without it, you are running on instinct and reflex.

Elaine Thompson didn't change the law. She didn't shorten Raymond's sentence by a single day.

But she gave him something more valuable than a pardon.

She gave him the ability to narrate his own life.

Raymond Cortez says it best. In an interview years later, he said:

"She didn't give me freedom. I'm still behind these walls. But she gave me a mind. And when I am reading, I am not in San Quentin. I am in 19th century France. I am in the Mississippi Delta. I am everywhere. And no guard can take that away from me."

This is the power of the "small" story. The story that never makes the headline.

It reminds us that redemption doesn't always look like a man walking out of prison gates. Sometimes, it looks like a 43-year-old man, sitting in a plastic chair, whispering "The dog ran home," and realizing that, for the first time in his life, he has finally found the way out of the dark.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.