Here's a story about a guy I only met once who still got me into college and, maybe more than any single other person, set me on my life's path. His influence on me happened purely by accident, because of a late flight. His name is Robert B. Parker, he was born in Maine and lived most of his life in Boston, and he was a writer. I'm gonna tell you all about him.

Every year I keep a list of the books I've read. Many authors appear in multiple years, some more than once in the same year, but only two have appeared in all the fifteen since I started. The first is Stephen King, because he has a massive catalogue, because most of his books are worth a second (or third or fourth) read, because he cranks out at least one new book every damned year-hopefully for a long time to come too-and also simply because he's great.

The second writer is a different story.

His name is Robert B. Parker, and even though I've read all his stuff and he's been dead since 2010 he still shows up every year. He put out quite a lot of work but even so there are few entries in his bibliography I haven't read at least twice. These days his annual appearances on my "Books Read" list are deliberate but for some time they were purely by accident, and because I want and need him to he'll make every subsequent year's list for as long as I make them.

I reread Parker because he’s a great writer; his prose is so damned smooth, addictive and compulsively readable that once you start even one of his lesser works you just keep going, I’ve gone through many of his books in one day, some in one sitting. My favorite way to describe his mastery of the craft is as he himself once said, according to the great Lawrence Block, people "just like the way it sounds." All that helps but it's just part of why I keep coming back to him.

So ok then, why?

I'll put it simple and plain, like he would: Robert B. Parker introduced me to "adult" fiction, fostered my love of literature, more than anyone else made me both want to and know I could be a writer, and provided a path through life I found worth emulating. Getting me into college is kind of a big deal too.

Let’s backtrack a bit. I’m twelve, browsing the Pittsburgh airport bookstore before my flight home to New Jersey because my flight was delayed. This was my first time flying alone other than the flight from Newark to the Burgh a week earlier, and I was feeling so very adult and important. As such I wanted an “adult” book, even if I didn't quite know what that meant. I'd been a reader for years and I had read a few books technically not meant for children-Bradbury, some teen thrillers (I'd recently graduated from R.L. Stine's "Goosebumps" to his more mature "Fear Street"), and most especially Michael Crichton. But even Crichton, whose Andromeda Strain and Jurassic Park were undoubtedly adult, wrote stories anyone could appreciate and, more importantly, underneath the scientific jargon, cursing, and violence were still "basic" enough for anyone to enjoy and appreciate. They felt like just slightly more sophisticated versions of the R-rated movies I'd been watching with my dad for years by then, which themselves were mostly just bloodier versions of the Saturday morning cartoons I grew up on with dirtier words and the occasional full-frontal nudity. Note: this is not at all meant to be a criticism of Crichton or Stine or Bradbury, it is merely the truth as I saw it at the time. I wanted something advanced, something complicated, something morally "gray". I didn't yet possess the vocabulary to describe it but I wanted something beyond my experience, something with moral complexity, with conflicts beyond straight good vs. evil, something where life and death weren't the only stakes and even when they were both meant more.

As I said I didn't consciously know any of this at the time. I just wanted something that looked good, and I knew my Aunt Kandy-unlike my mom or dad-would let me buy it. With my own money of course, that meant a lot as well then, I had about $48 to my name but at the time this felt like a fortune.

One cover jumped out at me: Walking Shadow. I’d never heard of the author, his name didn't grace any of the titles my parents left around the house I'd spent hours gazing at, but, man, that author photo on the back cover was so badass.

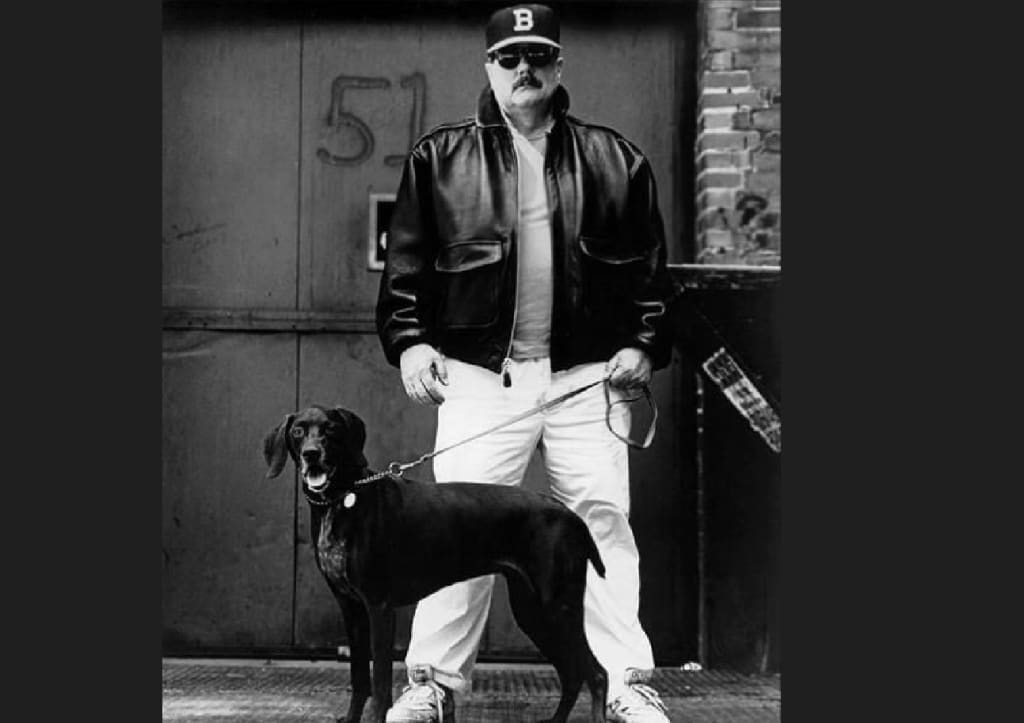

(See photo above)

A big man, not so much fat as youthful muscle spreading out to middle-aged girth, jeans and sneakers, plain red t-shirt under a black leather jacket, inscrutable sunglasses and old-school mustache beneath the brim of a vintage Boston Braves cap. One of his thick hands hangs open at his side, ready for action, the other is fisted around the leash of the German short-haired pointer standing alert in front of him. They appear to be in some back alley in front of a rusty loading bay, the building’s brick wall and the edge of a quintessential city dumpster just visible to one side. This man could be an off-duty security guard or bouncer, a cop or a criminal, in general someone you wouldn’t fuck with. "Fuck" was a word I knew well then but had only whispered to myself or written on notebook pages I immediately threw out by that point, but it was definitely the right word for what you wouldn't want to do with this bruiser. He looked tough but, and here's another singularity within my experience up to then, not threatening. Don't mess with him and he won't mess with you. He gave the impression of strong silence, not a reluctance to speak but the security of not needing to unless, until, he has something worth saying.

The book description was brief and vague, something about a P.I. named Spenser, just that single name, investigating a murder in the typical crime-ridden moral-decrepitude-beneath-the-glossy-veneer town of Port City. Still, that coupled with the author photo would have been enough for me but I was completely sold when I cracked the paperback open.

First came the endearingly elegant dedication: “For Joan: ‘Whom if ye please, I care for other none.’ (reproduced here from memory)."

Then the opening lines: "The last time I'd worked in Port City had been in 1989 when an important software tycoon had hired me to retrieve his wife, who had run off with a fisherman named Costa. Her name was, incredibly, Minerva, and I found her okay. She was living in a shack on the waterfront with Costa, who, when the fish weren't biting, which was mostly, worked as a collector for the local loan shark. This led Costa to believe that he was tougher than he actually was, a point he finally forced me to make."

The rest I'll paraphrase: after putting Costa in the hospital Spenser understood that Minerva truly loved him and decided to leave them be, which got him stiffed on his bill by and in legal trouble with the software tycoon. Spenser then mentions how the tycoon's later efforts to find his wife on his own were shut down by the local police chief and how years later he called Minerva to see how she and Costa were doing but found them gone, "I never knew where." The couple is not mentioned again.

So. In one paragraph Parker established Spenser as good at and well established in his job, tough, funny, adherent more to his moral compass than to money or fear of those in power, genuinely sensitive and caring about those he deems worthy, yet wise enough not allow the fates of others to bother him too much. All that plus establishing the voice of a character so strong and unique yet simultaneously familiar you just know this is Grade A prime cut hardboiled P.I. fare, even if you've never experienced it before, in less time than it took for me to write about it. Yeah, I was hooked.

I was damn near finished with the book before I got off the plane, and I clearly remember being annoyed the flight hadn't been longer.

Cut to four years later. I am once again in Pittsburgh, spring break of high school sophomore year, and that same aunt took me a signing event with the man himself promoting his latest Spenser novel Hush Money. I'd read five or six of the others by then and I was loyal devotee by then, and I was about as excited to meet Mr. Parker that April as I've been about anything before or since.

He was everything I’d hoped for: gruff yet articulate, New England laconic yet engaging, aware of his revered status-he either already was a Mystery Writers of America Grand Master or knew like everyone else who followed those things he soon would be-but still warm and open with healthy doses of humility and amusement regarding such, graciously fielding numerous inane and in some cases ridiculous questions from the audience. Pretty much exactly the way I imagined he, and Spenser, would be. Two of those inane, ridiculous questions came from me, by the way: one about an upcoming made-for-TV adaptation of his book Small Vices, which I suppose was all right, but the other one was pretty bad.

Parker had been talking about how he and Spenser were about the same age and the character was written in real time, and jagoff me said something along the lines of “So in every book Spenser is getting in fistfights and shootouts but he’s also your age?”

Parker agrees this is true.

“So, what’re you gonna do when you’re, like, 70?” This got a laugh from the audience, and I still cringe over it. Parker, who would’ve been 66 then, was unflappable, just shrugging and responding he’d worry about that when it happened. Even more embarrassing moves on my part came later, when my turn in line came to meet him. First I asked about his turn as a reader on the audiobook version of a Stephen King short story and he told me how much he’d hated doing it and would never do anything like it again. Then I gave him my copy of Hush Money and the slip of paper with what I wanted him to write above his signature: “To Tripp, my potential successor, Robert B. Parker.” Lord, the audacity. He wrote it without blinking an eye though, even adding a best wishes salutation, and said as he handed it back “Just give me a few more years though, ok?” What a class act, right? I still have the book, of course.

Cut to two more years later. I’m a high school senior, filling out college applications with some trepidation. My grades are for the most part just decent, no athletic activities (I eventually listed intramural soccer and volleyball out of desperation) and most of my extracurricular activities all but screamed last-minute college application fodder.

My potential saving graces? My grades in English, I planned to be an English major after all, my almost top-tier SAT scores-not to brag but also to brag a little on my second try at the test I cracked 1500-and my admission essay. Again I was planning to major in English and take as many lit and creative writing classes as possible so I was betting the house that, in my unearned confident teenage opinion, my blazing literary talent would seal the deal for me. I cranked out a bunch that were good and even a few that were great, but on one essay in particular I really shined. This one was for a small but respectably well-regarded liberal arts college in central Pennsylvania called Dickinson, among whose essay options was which literary character I most aspired to be like. You can guess who I chose.

I wrote about how Spenser had achieved what was, for me, an ideal existence: he was wholly, uniquely, his own person, with a career and indeed an entire life built on his own terms, dependent on and beholden to no one but himself. At his job, in his life and relationships, he did only what he wanted the way he wanted to do it, and was a success. He was the best at what he did, he was financially comfortable, respected and admired. He was well-liked with a core group of true friends he trusted completely and vice-versa. He had a decades-long committed relationship with the sort of great, unquestioned love-of-your-life partner most of us can only dream of, and while his relationship with Dr. Susan Silverman was atypical-they never married, lived in their own separate spaces and couldn’t be more different as individuals-it worked perfectly for them, and was the result of trials and errors over the years most couples could never have survived. But they did, knowing only that they belonged together and doing all the necessary work to ensure they were, no matter what form their relationship eventually took.

Spenser was an old school, a former boxer who could still outfight just about anyone, an ex-Marine who could shoot, hunt, and build a house with his own hands. Even into his sixties he ran daily, worked out with free weights and the heavy bag, and before his commitment to Susan was quite the ladies' man. But he was also a gourmet cook, a sharp dresser and a voracious reader who quoted Shakespeare, Donne and the Romantics regularly. His namesake was the Romantic Edmund Spenser, whose best-known work "The Faerie Queene" gave this essay its title and subtitle, though his first name is never revealed.

Spenser adhered to a personal code of honor resembling a medieval knight’s chivalry but allowed it to constantly evolve and frequently bent it when the situation required. He was almost shockingly sensitive and enlightened for a man of his time, sadly for a man of today too, unconcerned with matters of gender, race, class or sexuality, restricting any judgement to others' actions and attitudes. Even then he would often assist, stick with, and fight for people he didn’t understand or sometimes even like. He was a man of violence and gentleness, hard but emotional, cynical yet hopeful.

All this, to one degree or another, are all the things I hope to be, try to already be, and in some cases maybe already am. I have a father of my own, who's been present throughout my life and who taught me many invaluable lessons, but I'd be lying if I didn't count Robert B. Parker as a genuine father figure. There's certain things you just can't learn from your father/mother/uncle/aunt/sibling/etc. even if they tried teaching you. Sometimes some things have to come from a neutral source, including if not especially one who doesn't know you from a damn hole in the ground.

I got into Dickinson, I'm convinced, on the strength of that essay, and as you can all imagine a huge portion of my life was shaped by my time there: so much knowledge gained in the classroom and out, friends I have to this day, loves gained and lost and occasionally gained and lost again.

I think, now, I always wanted to be a writer, I've always had a natural talent for it and loved making up stories in my head if not on the page, but I didn't consciously decide it would be my chosen profession till age 17 or so. Parker, of course, wasn't the only author who inspired me to write, nor in all honesty was he the main one(s), but I can tell you the first time I ever tried writing something *for real* it was his voice and style and subject matter you could most clearly extrapolate from my work. Most of the major works I've both attempted and completed since then still bare at least a ghost image of his fingerprints. What can I say, I just like the way it sounds.

I've changed a lot since age twelve and in a lot of ways; I've never been a true conservative but these days I'm progressive enough to count as an ideological minority even among liberals, I've become anti-gun (at least as this this country would define it) and to say the least I'm nowhere near as impressed by or trusting in the military and the police as I was on the day I picked up Walking Shadow. For me though, then and now, Spenser not only embodies a masculine ideal (whatever that is and it's always changing as it should) but, which is more, a truly complete human being. He knew exactly who and what he was, found contentment in it, but at the same time was always evolving, reshaping, and perfecting himself. Parker himself was a version of his greatest creation, and his ideal has become mine. His own personal struggle and journey has become a similar goal.

Since the fateful morning in the Pittsburgh airport I've read not only all the Spenser novels but all Parker's other books, those featuring other continuing characters as well as stand-alones and collaborations. Seventy-two books in all, and none written before Parker's late thirties. Being around that age myself and, as of now, still unpublished, that last bit gives me a different sort of inspiration I'd never expected or considered in years previous. Even now, Parker is teaching and motivating and supporting me.

He never knew me, not really, and even in my most egotistically wild dreams I can't imagine he remembered me more than a matter of minutes after our sole in-person encounter.

But he's still a deep, implacable part of me. Has been for closing in on thirty years, and will be for as many as I have left in front of me.

Thanks to Aunt Kandy, thanks to whatever reason whatever airline I was flying that long ago afternoon had in pushing back my flight's departure, thanks to the Pittsburgh airport's newsstand for stocking a book that would, by about as pure an example of chance or coincidence as I can think of, completely and irrevocably change the course of my life.

But, of course, thanks most of all to Robert B. Parker. Thanks for the words, the work, the lessons, the life-I like the way they sound.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.