That Summer, the time they smashed the bus shelter, and glass crunched under us like fresh hail, our shoes kicking the cruel glitter from school to the Co-op’s aerosol slang, I sat down to think about the meaning of it all. Really think. In that way only seven year olds can.

‘Penny for your thoughts.’ You’d said, as the sun blazed the curtains on our top floor, killing the 5 o'clock sit-down news.

‘My thoughts aren't worth that much, Gran.’ Half-smirk, I’d turned and watched the green birds swag their ruffled tongues, dreggy and wet grey to the speck air. Pelting below in disco shorts, that guy we knew but not his name, his headphones shouting tinny.

I’d never told anyone my thoughts. When I said them out loud they’d sound flighty, like they were made of reed fluff and might be taken up in the first gusty breeze and split apart, across the rail-track.

If I ever thought about anything, it was about the things that live out on the marshes, on the wide expanse that sweeps outwards under a turning sky, a continuous kaleidoscope of colour and light. Ancient breeds of grazing cattle that would appear like a mirage once a year. Rarest plants of scientific interest, creeping marshwort, the elusive Essex skipper butterfly, and soft pyralid moths. Multitudes of birds would winter here and the finches feasting in Autumn reeds. Flocks of parakeets swelled each season and shimmer their green over the water, bending in mobius strip.

Every so often, floods would burst our river and mirror the sky. If you walked down there it could be hard to tell which way was up. And I couldn't always protect the creasy, crested newts who’d nuzzle at my thumb.

‘Here.’ You’d shoved me a little black book as you took off your yellow nylon cardy, sparking the air in static blue snaps. And wrapped on your apron for tea.

‘Put your thoughts in there instead, for me?’

Your slate blue eyes had raked through me, concerned no doubt that at school I had no friends, no interest in other people.

I looked after you but mostly you looked after me.

So I had written in the little black book. Thoughts. But not stories, I hated stories. I hated stories because they were always trying to persuade you of things that weren't entirely true. And most didn’t even succeed. I liked true stuff. So I kept notes of all the creatures I loved in the valley, the colours of the sky and the leaves that change. And slowly, began to put my thoughts in too. And you never looked or asked, but smiled as you passed, like you’d remembered a good day out.

After Mum had one day upped and gone, you’d disappeared into a twilight world. Inside our flat an eternal dark, to boost the tiny TV screen, blot out dreaded bright lit days, their thick claws of sunshine, reaching through gaps in your curtains. Like long slow searchlights, they’d pick out your Sacred Hearts around the mirror, your tiny gold-label liquor bottles glinting in a wicker basket by the armchair. You had looked for answers in the church and then lost them in a bottle. Too young to understand, I had searched too, in snail shells and tapped stones. Mum wrote fairy tales promising 'I’ll come soon' and 'Wish you were here' on the back of weather-worn sea-side postcards. I even awoke some nights and thought I saw her. Sat in the dark watching me, still as a moth on a wall.

‘Was Mum here last night?’ Each time I’d ask.

‘No, love.’

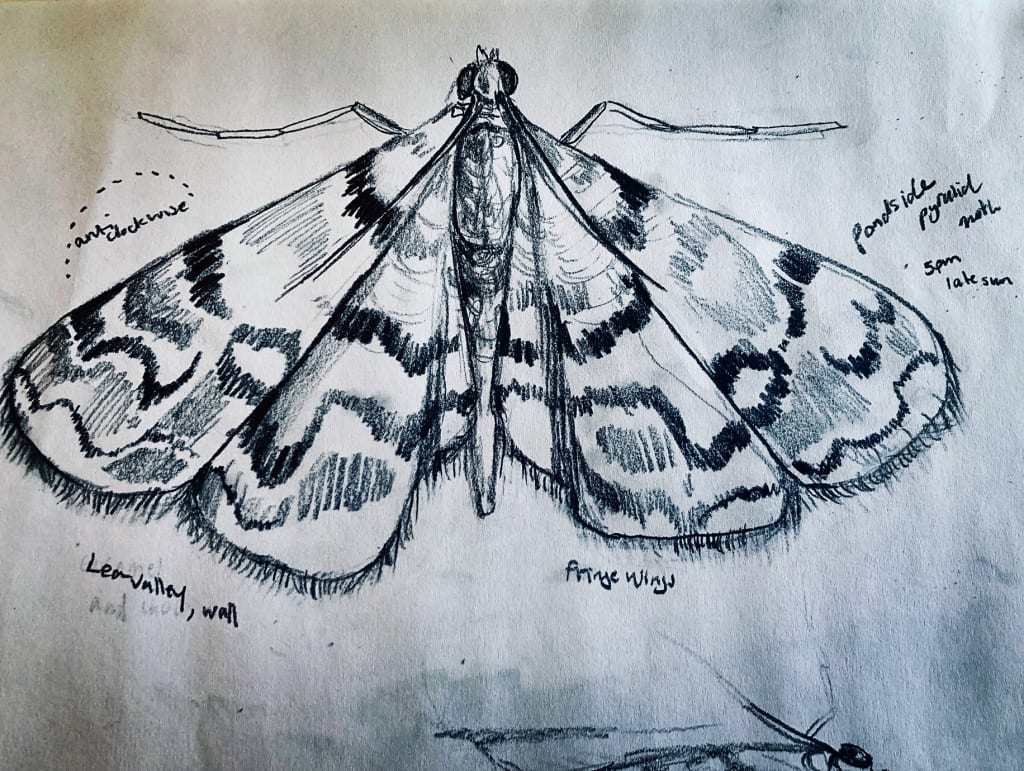

So instead I studied pyralid moths, wrote down everything I could see about them, the way they behaved, the shape and pattern of their wings, how they moved anti-clockwise. The finger like projections from their mouths that point upwards like little snout. I wrote and wrote in the black book. And over the years the book became filled with all the details of things I knew to be true. And so I bought another and another. Each growing fat with facts.

Until one day I grew up, I guess, and I stopped. The valley outside now seeded with concrete and steel. And by then you had got so forgetful and tired. You went to bed and didn’t get up again. All your memories leaking out of your head like air from a nicked balloon.

The wind comes up the valley, block-heavy flowers blown out like bulbs. Reeds swaying like the slow-mo-slap of advert shampoo. Water skimmers in the first gold of day, show pin-prick bends in sky. I walk back past the Co-op, newly painted, the years of paint now bubbled. And the bus shelter, its still crashed glass wedges itself in the groove of my boots.

I air the flat, open the windows, slip the sheet off your bed. Catch your snotted hanky rosettes. Under the mattress, as I untuck the valence, I tip over an old fudge tin and a shlink of coins gush out, thick silver across the floor. More are stacked under the bed, heavy, a hundred at least, each brimful. Must be thousands of coins here. And on each tin, in your spidery hand you have written my name, 'Penny', and the words 'for your thoughts.’

The evening comes and I sit on your stripped bed, the window open over the river. I read out all the facts from my little black books, calling up each rare newt, each spotted pyralid and sunsets of lilac-tangerine. And I almost come close to the meaning of it all.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.