Red Mittens

Scissors, red paper, and an island off the coast of Maine.

Of the more than 3,000 islands off the Maine coast, only 15 are both inhabited year round and unbridged. Many of these islands, accessible only by boat or aircraft, serve as summer enclaves to wealthy Floridians and New Yorkers who alight on their magnificent houses for a few weeks each summer before taking off again, leaving behind the small communities that keep the islands running through long winters and cold springs. At least that’s the case on this island, where I moved a few years ago after getting a job at the local Post Office.

In most of Maine, there is a profound distrust of the outsider, those “from away,” as they’re called, and in some corners it takes three or more generations to bear the badge of a true local. So when I, a California native, got a job at a Post Office on an island off the coast of Maine, I anticipated a great deal of standoffishness, if not outright hostility. Surely the locals would bristle at someone “from away” entering their world.

But it seemed this distinction of local and foreigner could blur a little on an island, a place that attracts wilder characters--transients, creatives, anyone willing to try the inconvenience and strangeness of life on a little chunk of rock poking out of the ocean. Rather than generations of breeding to become “one of them,” many of the islanders seemed to require only persistence: if I could stick it out, (maybe) I would be in.

The animosity I feared did not materialize. The fact that I moved to the island rather than commuting from the mainland seemed to set people at ease. They invited my husband and me into their homes, fed us from their gardens, invited me to gather wild blueberries from their fields.

I was informed repeatedly that not everyone on the island necessarily liked one another or even got along, but they were always there for one another in times of need. Summer Person or Islander, relative or enemy (sometimes both), people pitched in for one another. I didn’t anticipate seeing this play out so quickly, but then came the pandemic.

Things in the community were tense in the early days of COVID. With an aging population and limited medical services, suspicions and disagreements simmered across the island. Every business other than the Post Office closed to walk-in customers. The cheerful, close community went quiet, wary, and before long, like people around the world, they grew tired and lonely. Grandparents couldn’t hug grandkids who lived down the road, the churches stopped meeting in person, and all the other little community groups, from the sewing circle to the pickle ball team, stopped gathering. Community, the thing the island always had, suddenly seemed fragmented. People who prided themselves on being there for each other were forced apart.

It didn’t take them long to find ways to support each other, though. Local organizations and cooks got together and prepared beautiful hot meals for islanders every week. More than once I found myself tearing up at the trays of hot food left quietly in the front seat of my car, my name circled with a heart. This was not the sort of kindness and generosity I was accustomed to in the world.

For my part, I was acutely aware that for many who came into the Post Office, I was the only person they would see all day, or all week. Some mailed presents to grandchildren they had never met, relatives they’d never been apart from for this long. While my day to day life was largely the same--save for the addition of masks, barriers, and copious cleaning requirements--theirs were often dramatically different. So I tried to be cheerful and present and spend extra time talking to people. They had so much to say, and when I wasn’t exhausted, I felt grateful to be the person they chose.

As the holidays rolled around, one of the islanders asked me if I was planning anything for the holiday decorations.

“I’m telling everyone we should light up the island,” she said. “We all need it.”

I told her I would see what I could do, but internally I wasn’t optimistic. At home we only had enough Christmas lights to decorate our tree, and it’s not like the Post Office has a decorating budget. I searched the office for anything that might add some spirit, and did find a shoebox of holiday decorations in the custodial closet. It’s contents: a felt elf hat, blank Christmas cards, and an ornament made of yarn. Not exactly the stuff holiday wishes are made of.

Returning to my search, I weighed my own pandemic fatigue against the desire to brighten people’s lives at the end of a rough year. I didn’t want to let people down, but it felt like I had nothing left to give. But the island had already taught me what to do when I wasn’t able to do something myself. Looking around the office, my eyes fell on a ream of red paper.

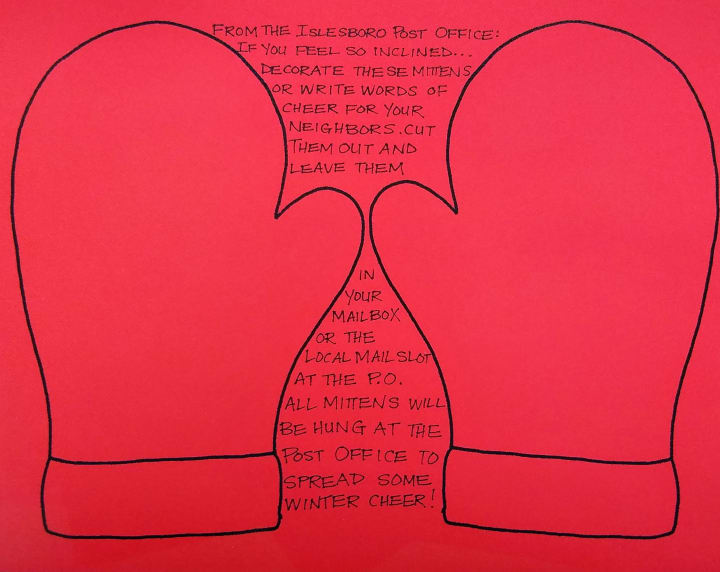

If I couldn’t decorate something big for everyone, maybe everyone could decorate something small for all of us. I printed the outline of a pair of mittens with a message written between them asking people to decorate them, cut them out, and drop them off at the Post Office. Any more elaborate project would be challenging to coordinate or plan, but I knew that everyone on the island could participate in this because everyone has a pair of scissors and something to draw or write with. After giving these simple outlines on red paper to everyone on the island, the island returned to me more than I could have imagined. Brilliant bits of creativity, love, and comfort cut from a piece of paper.

The mittens came back bedazzled, glittered, painted, and adorned in all kinds of decorative flourishes: feathers, fabric, pipe cleaners, pasta pompoms, even jingling bells. Self portraits, an illustration of the local lighthouse, words of thanks to the grocery clerks across the street, photos and drawings of grandkids, pets, and cosy winter scenes. One enterprising islander turned her mittens into dog toys with squeakers and stuffing and fabric and ribbons.

I put them all over the walls, hung a garland of them across the window, had them surrounding the retail window. When people came into the Post Office they lingered to look over the mittens, little giggles or cheerful notes of recognition when they saw their mitten or the handiwork of a friend.

For my own mitten, I slowly covered the red paper in layer upon layer of blue colored pencil. Creating smooth shading with colored pencils, and building a smooth, opaque surface that fades from deep to powder blue, requires a great deal of time. This gradual and methodical labor became a kind of meditation that I could pick up and dissolve into after work. I sat by the fire with the dog or one of the cats in my lap, watched episodes of The Office, and sharpened all the shades of blue. This was the peace I needed. I sliced the mitten free of its red page and let it drift onto the table like a big blue snowflake.

Come spring, the town held vaccination clinics at the island school, and now, according to Maine CDC data, virtually everyone on the island is immunized.

As another summer season comes around, faces I haven’t seen in two years are poking back into the Post Office. I try to remember as many as I can, to affirm whenever I can that I have hung on to something about them--the name of a child or pet, their hometown or hobby. I’m not naturally good with names, so I repeat them in my head over and over as soon as they say it. People want to be seen, to be remembered, to be known in some way. Behind a mask, beneath the surface, and maybe on a mitten.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.